a&e features

Sean Doolittle: The all-around All-Star

Nats pitcher, wife on life in D.C., their LGBT advocacy — and whether the team is ready for a gay player

Ace relief pitcher Sean Doolittle was traded from the Oakland Athletics to the Washington Nationals in July of 2017. He eloped with his then-girlfriend, Eireann Dolan one day after the regular baseball season ended last year. Doolittle was named a 2018 All-Star this week; he was a member of the 2014 MLB All-Star team and this season is rounding out to be one of the best of his career.

Doolittle and Dolan received national attention in 2015 when they purchased hundreds of tickets to the Oakland Athletics Pride Night after the event received backlash from fans. The tickets were donated to local LGBTQ groups and an additional $40,000 was raised.

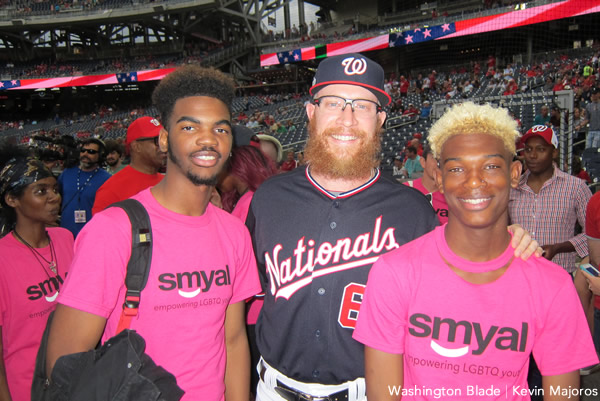

Sean Doolittle on the field with members of SMYAL at Night Out at the Nationals. (Washington Blade photo by Kevin Majoros)

Local LGBTQ youth leadership and housing program, SMYAL, has caught the attention of Doolittle and Dolan and they donated 52 tickets to the organization for Night OUT at the Nationals last month. Going a step further, they stopped in personally to deliver the tickets at the SMYAL youth program’s headquarters and the SMYAL transitional housing program.

The Washington Blade sat down with the couple inside Nationals Park for a conversation about the LGBTQ community, life in D.C., baseball and music.

Eireann Dolan and Sean Doolittle (Washington Blade photo by Michael Key)

Washington Blade: You’re both active with charitable causes including work with Syrian refugees and military veterans’ mental health and housing. How did you become interested in the LBGTQ community?

Eireann Dolan: I have two moms. But even if I didn’t, I think this is something that’s really important. It’s always been really important, at least in my family. And something that we’ve always valued is the idea of having an accepting place. Having a sense of home. It factors into all the charity work that we do, all of the community work. We work with the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR. We’re going to have about 30 refugees coming to the game tomorrow night.

Blade: That’s incredible.

Dolan: Yeah, so we’re going to have them on the field and they are veterans who are injured or widowed. We deal with housing for them. Our theme seems to be a sense of home. Making sure people feel welcome. Whether they’re a refugee, whether they’re a veteran returning or transitioning back into civilian life, or whether they’re somebody in the LGBTQ community who maybe hasn’t considered that sports would be a space for them. We want to make sure that they know it is a space for them. They do have a home here and we accept them as they are. It’s always been really important to us.

Blade: And then you stumbled upon SMYAL here in D.C.

Dolan: We did. Well, it kept getting name dropped to us so many times by so many people.

Doolittle: In advance of the Nationals Pride night, we wanted to get involved. We wanted to do something more than catch the first pitch or meet some people on the field before the game. And we love this community, we love being here, and we wanted to give back. And like she said, in some of the meetings we had with the folks here, with the Nats, SMYAL had been referenced several times. We were able to make a couple visits over there before Pride night.

Dolan: That was incredible.

Doolittle: It’s an incredible organization and the holistic approach that they take, helping with everything from housing to leadership to education to helping people become voices in their communities.

Dolan: That was the biggest thing, I think.

Doolittle: And then coming back. They go through the program and then they come back to SMYAL to give back and pay it forward. That was something that we found to be incredibly inspiring. And if, through this process, we can lift their voices up and help tell their stories, that’s what we’re trying to do.

Blade: Do either of you have any thoughts as to why Major League Baseball has never had an openly gay player? There seems to be upper management support, team player support and fan support.

Dolan: There’s a lot of hesitation for any athlete, and baseball particularly, to share a lot of their private life, just full stop. Baseball is a bit more buttoned-up. The players themselves are not marketed in such a way, or they don’t maybe market themselves in such a way that talks about their personal life. You look at basketball, you look at football, you look even at hockey. You know the spouses. You know the families. You know what they do. You know where they’re from. But in baseball, it’s a little bit different. I think that may contribute to it, but that, I don’t think is the answer entirely.

Doolittle: I do think there is growing support, like you talked about. I think Major League Baseball’s taken steps towards it. I still think there are steps that need to be made in educating more people. I think as we continue to make it a better space, a more accepting space, we can continue to get rid of all this toxic masculinity bullshit that happens in a locker room.

Blade: Does it happen here with the Nationals?

Doolittle: Of course it happens. It’s performative. Sometimes that’s a guy’s way of psyching themselves up to go play. But I think we’re seeing less and less of it, and it’s fallen by the wayside. We just need to be continuously focused on creating a space that’s accepting. When you’re with these guys in such close proximity over six, eight months over the course of the season, guys should be OK with being themselves. Whether it’s you’re gay or whether it’s a different religion, or you’re from a different country. We have guys in here from how many different countries? How many different religious backgrounds? So I think just continuing that evolution in the clubhouse.

Dolan: That sports era of the ’90s, early 2000s of hyper-masculine, almost borderline toxic masculine, alpha, humiliate your opponent, keep your head down, don’t look like you’re having fun. That’s waning because fans want fun. They like the back flips. They like the personality. And you’ve got guys out there, you’ve got little pockets of people showing their personality.

Blade: Do you think this team is ready for a gay player?

Doolittle: I don’t know. And that’s the thing, I don’t think we’re going to know until that happens. I wish I had a better answer.

Dolan: I think baseball is ready and I think clubhouses know if a guy can help your team, period, the end. Doesn’t matter.

Blade: What’s your take on the NFL’s anthem protest?

Dolan: It’s not an anthem protest, that’s my first thing. They’re not protesting the anthem, they’re protesting the violence against young African-American men, particularly.

Doolittle: I think the NFL’s response was incredibly dangerous and disgusting. You’re punishing guys by policing peaceful protesting. I think it sends a really bad message across the United States.

Dolan: And if you say no politics in sports, then how do you explain flyovers that you do before games? How do you explain all the active recruiting that they do for the military during games? Why are we picking and choosing? When you’re telling young African-American men, “We want to watch you, we want to watch you do this particular thing, but don’t talk,” that just smacks of something that I thought this country had moved past.

Doolittle: I think it could have been a relatively short-lived story with a much better ending if, initially, they had focused their energies on listening and trying to figure out a way to get guys to stand. So when Kaepernick starts kneeling, they start listening to his message. They help him get involved to focus that message into action in the community. And soon enough, we have guys that are proud to stand up for the anthem because they’re helping their communities and bettering people and remedying the situation. And I think, unfortunately, it’s been used as something in this culture war that we’ve seen. These guys have done a lot of incredible work in their communities. They’ve met with government officials, they’ve done a lot of outreach with law enforcement in their communities. They are backing it up with significant action. So I wish everybody felt good enough and proud enough to stand for the anthem without being told that they had to do so.

Blade: Would you go to the White House if the Nats win the World Series?

Doolittle: People have asked me that before, and you don’t get to answer that question unless you win the World Series

Dolan: We’ll talk to you in October.

Blade: As a relief pitcher, you’re either the hero or the goat. How do you deal with that on a daily basis? Do you have stress techniques?

Doolittle: I’ve gotten a lot better at it over the last couple years. Early in my career, I pitched with a lot of emotion and I put a lot into, like you said, whether you’re the hero or the goat in that scenario. There’s no gray area in that line of work. There’s no, well I thought I executed my pitches really well, I just didn’t get the results I wanted. That’s not a great consolation prize for you or the other 24 guys on your team.

Dolan: And the fans don’t want to hear it.

Doolittle: Yeah, and it’s tough to explain that away. I was very attached to how I was pitching, and if I was getting the job done. If I didn’t get the job done, that was a blow to my self-esteem. Over the last few years, I worked a lot at processing the outings, mentally preparing for the outings, changing the way that I use that energy. I used to pitch with a ton of emotion. Now, I use the energy to hyper focus. I want to calm things down. I want things to be slow and smooth.

Dolan: You’re very Zen.

Doolittle: I think it’s helped me manage a lot of that stress. It’s not always easy, but it’s an occupational hazard.

Blade: Your stats this year are amazing and…..

Dolan: Don’t say them, don’t say them, don’t say them.

Blade: All right. Don’t say them out loud?

Dolan: No. We’re very superstitious.

Blade: Are the stats that shall not be named a result of your comfort level in D.C. or are you doing something different in training?

Doolittle: I feel very comfortable in D.C. We love it here. I changed some things. But a lot of it was behind the scenes. We changed a lot with the arm care program that I have. I dealt with some shoulder injuries in the past, when I was with Oakland, and I missed some time on the disabled list, and I think sometimes, just getting a fresh set of eyes or a new way of explaining things, really helps. And we added some things to that program, to the daily routine. I feel strong. I feel, at this point in the season, even with the work load I’ve had, I feel really good about where my body’s at, and I think when you don’t have to worry every day about, how’s my arm going to feel when you come to the field, you can throw yourself into focusing on your outing and who you might face rather than focusing on trying to get your body ready to pitch. So that’s been a load off my shoulders, pardon the pun.

Dolan: Did you catch the eye roll on the recording? Was it loud enough?

Blade: You had an unusual path to becoming an MLB relief pitcher. You pitched growing up and also played first base at University of Virginia. And then, you were drafted by the Oakland Athletics as an outfielder and a first baseman. Is this where you were supposed to be the whole time? There was a little side path.

Doolittle: I feel like it is. It’s a lot easier for me to say this now, but I’m glad I went through that transition process. There were some really dark times. I missed three full seasons on the disabled list in the minor leagues.

Dolan: So close to getting a call up, too. He was right on the cusp.

Doolittle: And before I got hurt the first time in 2009….

Blade: As a first baseman?

Doolittle: As a first baseman, yeah. It’s totally shifted my perspective on everything. This almost didn’t happen at all. In 2011, I had contacted my agent to go back and try and figure out the process of re-enrolling in college, because I was that far at the end of my rope. And the A’s came to me and said, “Hey, would you like to think about pitching?” I joke that I took the scenic route to the big leagues. It makes me appreciate every day that I get to wear that little logo on the back of my hat that says I’m in the big leagues. It came really close to never happening.

Dolan: There’s something to be said about having experienced adversity and failed. I don’t think I would be with him if he was this super successful player. I don’t think I would have been drawn to him.

Doolittle: Right, you learn a lot of humility, you learn a lot about yourself.

Dolan: Yeah. If you’d been that first round pick that you were, superstar first baseman….

Doolittle: I was the man.

Dolan: You were the man.

Blade: You prefer him damaged?

Dolan: That’s right up my alley. Who else is going to humble him, honestly?

Blade: What are you liking about living in D.C.?

Doolittle: It’s an awesome city. There’s a good energy, there’s a creative energy, it’s very diverse, it’s very accepting. The sense of community, the pride of being from D.C., that’s a thing that we found that I think was really cool. There’s a lot that we like about it.

Dolan: It’s amazing. We love the local bookstores and local record shops. We love just discovering new, cool spots that we can hit up every time we have a spare hour or so.

Blade: What about the excitement of MLB All-Star Week being in the town where you’re now pitching?

Doolittle: I think it’s awesome. I think us players, we’re starting to feel that buzz and that energy surrounding it. I’m excited for the Nationals fans and the organization, because they’ve done everything so first class. There’s a good energy surrounding D.C. sports now, and I think to bring the best players from around baseball here to D.C., that’s going to be really cool.

Blade: Has the Stanley Cup win by the Washington Capitals affected the team in any way?

Doolittle: We definitely followed it as a team. Before or after our games, whenever the Caps were playing, the TVs in the clubhouse were on. We were following it on our phones, or any chance we could, we were watching the game. We were all in, and I think it was great for us because they gave us the blueprint. They showed us how it’s done. They’ve had a similar storyline. They’ve had to answer a lot of the same questions we’ve had to answer after having really successful, regular seasons, but not making the deep run into the playoffs. They’ve had to answer the questions, is this the year you get over the hump? How are you guys going to break through?

So to see them do it, and to see them break through and not stop, and keep going. It was really fun. And when they came here, that was the biggest thing that they said. It was really cool to share that experience, just for a little bit, with the Cup, in the locker room and on the field.

Even though it’s a different sport, that energy, you can feel it. We’ve had Champagne celebrations before, and once you get a taste of that, you want more. And that’s really motivating, to have another team in your city bring in a trophy like that.

Dolan: And to see the parade and the reaction from the fan base. This is a sports city. And I don’t think people give it enough credit for being the sports city that it is. It was a nice taste.

Blade: Sean, you are a Star Wars fan and your Twitter handle is Obi-Sean Kenobi. Was the Solo movie a win or lose for you? Did you go in costume?

Doolittle: I loved it and we didn’t go in costume this time. We were in Miami, so we were on the road. But we did see it opening night.

Dolan: It was really hot there; a Chewbacca costume would have been difficult.

Doolittle: Yeah. And I don’t know if I can pull off a Princess Leia bikini.

Dolan: Not to say we haven’t tried. There’s your cover picture.

Blade: What’s on your music playlist right now?

Doolittle: I’m a metalhead. I was raised on the sounds of Black Sabbath and Ozzy, AC/DC and Metallica, and my love for it grew from there. When we were kids, we would be going to a Little League game. I’d be nine years old and we were rolling up in the minivan, blasting Black Sabbath.

Dolan: Oh, bad, bad. Love it.

Doolittle: There’s a band from Texas called Power Trip. They’re new but their sound is very ’80s thrash, which I really dig. There’s another band call Chemist. It’s called doom metal. It’s a lot slower and they have some good stuff. I really only listen to it when I’m at the field. When we’re at home, it’s a lot more mellow.

Dolan: We’re pretty eclectic at home. It’s not all metal for us. We like a lot of the new Nashville sound. I’m not a huge country fan, but Sturgill Simpson and….

Doolittle: Jason Isbell.

Dolan: And Colter Wall, yeah. A lot of that is really good. And I love hardcore gangster rap, honestly. I’m not going to lie, it’s my weakness. When he’s pitching, I put on noise canceling headphones and blast gangster rap. Tupac or Biggie, and it works. It calms my nerves because there’s something about it.

Blade: There are nerves for you while he’s pitching?

Dolan: I don’t watch, no. I haven’t watched him pitch live in years. I’m too superstitious.

Blade: Give me a quirk about the other person that makes you laugh.

Doolittle: Oh my god.

Dolan: He has a tactile thing about mesh.

Doolittle: It’s very soft.

Dolan: He likes to touch mesh.

Doolittle: Quirks that make me laugh….

Dolan: Careful, careful.

Doolittle: Well the aforementioned noise canceling headphones, she likes them so much that she’s taken to wearing them in the shower.

Dolan: They’re large speakers and I have three separate shower caps.

Doolittle: She took 45 minutes in the bathroom recently and I was like, what is going on? I was knocking on the door. She didn’t hear me.

Dolan: I bought a deep conditioner mask. Listen, this hair doesn’t get like this on its own.

Blade: Sean, we need to get you to practice. Let’s grab a photo first.

Dolan: Cool.

Doolittle: Oh, cool.

Dolan: All right. Don’t forget your dry cleaning, Sean. We want that front and center in frame.

Sean Doolittle and Eireann Dolan (Washington Blade photo by Michael Key)

a&e features

What to expect at the 2024 National Cannabis Festival

Wu-Tang Clan to perform; policy discussions also planned

(Editor’s note: Tickets are still available for the National Cannabis Festival, with prices starting at $55 for one-day general admission on Friday through $190 for a two-day pass with early-entry access. The Washington Blade, one of the event’s sponsors, will host a LGBTQIA+ Lounge and moderate a panel discussion on Saturday with the Mayor’s Office of LGBTQ Affairs.)

With two full days of events and programs along with performances by Wu-Tang Clan, Redman, and Thundercat, the 2024 National Cannabis Festival will be bigger than ever this year.

Leading up to the festivities on Friday and Saturday at Washington, D.C.’s RFK Stadium are plenty of can’t-miss experiences planned for 420 Week, including the National Cannabis Policy Summit and an LGBTQ happy hour hosted by the District’s Black-owned queer bar, Thurst Lounge (both happening on Wednesday).

On Tuesday, the Blade caught up with NCF Founder and Executive Producer Caroline Phillips, principal at The High Street PR & Events, for a discussion about the event’s history and the pivotal political moment for cannabis legalization and drug policy reform both locally and nationally. Phillips also shared her thoughts about the role of LGBTQ activists in these movements and the through-line connecting issues of freedom and bodily autonomy.

After D.C. residents voted to approve Initiative 71 in the fall of 2014, she said, adults were permitted to share cannabis and grow the plant at home, while possession was decriminalized with the hope and expectation that fewer people would be incarcerated.

“When that happened, there was also an influx of really high-priced conferences that promised to connect people to big business opportunities so they could make millions in what they were calling the ‘green rush,'” Phillips said.

“At the time, I was working for Human Rights First,” a nonprofit that was, and is, engaged in “a lot of issues to do with world refugees and immigration in the United States” — so, “it was really interesting to me to see the overlap between drug policy reform and some of these other issues that I was working on,” Phillips said.

“And then it rubbed me a little bit the wrong way to hear about the ‘green rush’ before we’d heard about criminal justice reform around cannabis and before we’d heard about people being let out of jail for cannabis offenses.”

“As my interests grew, I realized that there was really a need for this conversation to happen in a larger way that allowed the larger community, the broader community, to learn about not just cannabis legalization, but to understand how it connects to our criminal justice system, to understand how it can really stimulate and benefit our economy, and to understand how it can become a wellness tool for so many people,” Phillips said.

“On top of all of that, as a minority in the cannabis space, it was important to me that this event and my work in the cannabis industry really amplified how we could create space for Black and Brown people to be stakeholders in this economy in a meaningful way.”

“Since I was already working in event production, I decided to use those skills and apply them to creating a cannabis event,” she said. “And in order to create an event that I thought could really give back to our community with ticket prices low enough for people to actually be able to attend, I thought a large-scale event would be good — and thus was born the cannabis festival.”

D.C. to see more regulated cannabis businesses ‘very soon’

Phillips said she believes decriminalization in D.C. has decreased the number of cannabis-related arrests in the city, but she noted arrests have, nevertheless, continued to disproportionately impact Black and Brown people.

“We’re at a really interesting crossroads for our city and for our cannabis community,” she said. In the eight years since Initiative 71 was passed, “We’ve had our licensed regulated cannabis dispensaries and cultivators who’ve been existing in a very red tape-heavy environment, a very tax heavy environment, and then we have the unregulated cannabis cultivators and cannabis dispensaries in the city” who operate via a “loophole” in the law “that allows the sharing of cannabis between adults who are over the age of 21.”

Many of the purveyors in the latter group, Phillips said, “are looking at trying to get into the legal space; so they’re trying to become regulated businesses in Washington, D.C.”

She noted the city will be “releasing 30 or so licenses in the next couple of weeks, and those stores should be coming online very soon” which will mean “you’ll be seeing a lot more of the regulated stores popping up in neighborhoods and hopefully a lot more opportunity for folks that are interested in leaving the unregulated space to be able to join the regulated marketplace.”

National push for de-scheduling cannabis

Signaling the political momentum for reforming cannabis and criminal justice laws, Wednesday’s Policy Summit will feature U.S. Sens. Raphael Warnock (D-Ga.), Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), and Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), the Senate majority leader.

Also representing Capitol Hill at the Summit will be U.S. Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-D.C.) and U.S. Reps. Earl Blumenauer (D-Ore.) and Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) — who will be receiving the Supernova Women Cannabis Champion Lifetime Achievement Award — along with an aide to U.S. Rep. David Joyce (R-Ohio).

Nationally, Phillips said much of the conversation around cannabis concerns de-scheduling. Even though 40 states and D.C. have legalized the drug for recreational and/or medical use, marijuana has been classified as a Schedule I substance since the Controlled Substances Act was passed in 1971, which means it carries the heftiest restrictions on, and penalties for, its possession, sale, distribution, and cultivation.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services formally requested the drug be reclassified as a Schedule III substance in August, which inaugurated an ongoing review, and in January a group of 12 Senate Democrats sent a letter to the Biden-Harris administration’s Drug Enforcement Administration urging the agency to de-schedule cannabis altogether.

Along with the Summit, Phillips noted that “a large contingent of advocates will be coming to Washington, D.C. this week to host a vigil at the White House and to be at the festival educating people” about these issues. She said NCF is working with the 420 Unity Coalition to push Congress and the Biden-Harris administration to “move straight to de-scheduling cannabis.”

“This would allow folks who have been locked up for cannabis offenses the chance to be released,” she said. “It would also allow medical patients greater access. It would also allow business owners the chance to exist without the specter of the federal government coming in and telling them what they’re doing is wrong and that they’re criminals.”

Phillips added, however, that de-scheduling cannabis will not “suddenly erase” the “generations and generations of systemic racism” in America’s financial institutions, business marketplace, and criminal justice system, nor the consequences that has wrought on Black and Brown communities.

An example of the work that remains, she said, is making sure “that all people are treated fairly by financial institutions so that they can get the funding for their businesses” to, hopefully, create not just another industry, but “really a better industry” that from the outset is focused on “equity” and “access.”

Policy wonks should be sure to visit the festival, too. “We have a really terrific lineup in our policy pavilion,” Phillips said. “A lot of our heavy hitters from our advocacy committee will be presenting programming.”

“On Saturday there is a really strong federal marijuana reform panel that is being led by Maritza Perez Medina from the Drug Policy Alliance,” she said. “So that’s going to be a terrific discussion” that will also feature “representation from the Veterans Cannabis Coalition.”

“We also have a really interesting talk being led by the Law Enforcement Action Partnership about conservatives, cops, and cannabis,” Phillips added.

Cannabis and the LGBTQ community

“I think what’s so interesting about LGBTQIA+ culture and the cannabis community are the parallels that we’ve seen in the movements towards legalization,” Phillips said.

The fight for LGBTQ rights over the years has often involved centering personal stories and personal experiences, she said. “And that really, I think, began to resonate, the more that we talked about it openly in society; the more it was something that we started to see on television; the more it became a topic in youth development and making sure that we’re raising healthy children.”

Likewise, Phillips said, “we’ve seen cannabis become more of a conversation in mainstream culture. We’ve heard the stories of people who’ve had veterans in their families that have used cannabis instead of pharmaceuticals, the friends or family members who’ve had cancer that have turned to CBD or THC so they could sleep, so they could eat so they could get some level of relief.”

Stories about cannabis have also included accounts of folks who were “arrested when they were young” or “the family member who’s still locked up,” she said, just as stories about LGBTQ people have often involved unjust and unnecessary suffering.

Not only are there similarities in the socio-political struggles, Phillips said, but LGBTQ people have played a central role pushing for cannabis legalization and, in fact, in ushering in the movement by “advocating for HIV patients in California to be able to access cannabis’s medicine.”

As a result of the queer community’s involvement, she said, “the foundation of cannabis legalization is truly patient access and criminal justice reform.”

“LGBTQIA+ advocates and cannabis advocates have managed to rein in support of the majority of Americans for the issues that they find important,” Phillips said, even if, unfortunately, other movements for bodily autonomy like those concerning issues of reproductive justice “don’t see that same support.”

a&e features

Juliet Hawkins’s music defies conventional categorization

‘Keep an open mind, an open heart, and a willingness to evolve’

LONG BEACH, Calif. – Emerging from the dynamic music scene of Los Angeles, Juliet Hawkins seamlessly integrates deeply soulful vocals with contemporary production techniques, crafting a distinctive sound that defies conventional categorization.

Drawing inspiration from the emotive depth of Amy Winehouse and weaving together elements of country, blues, and pop, Hawkins’ music can best be described as a fusion–perhaps best termed as soulful electronica. Yet, even this characterization falls short, as Hawkins defines herself as “a blend of a million different inspirations.”

Hawkins’s musical palette mirrors her personae: versatile and eclectic. Any conversation with Hawkins makes this point abundantly clear. She exhibits the archetype of a wild, musical genius while remaining true to her nature-loving, creative spirit. Whether recording in the studio for an album release, performing live in a studio setting, or playing in front of a live audience, Hawkins delivers her music with natural grace.

However, Hawkins’s musical journey is far from effortless. Amid personal challenges and adversity, she weaves her personal odyssey of pain and pleasure, transforming these experiences into empowering anthems.

In a candid interview with the Blade, Hawkins spoke with profound openness and vulnerability about her past struggles with opiate and heroin addiction: “That was 10 years ago that I struggled with opiates,” she shared. Yet, instead of letting her previous addiction define her, Hawkins expressed to the Blade that she harbors no shame about her past. “My newer music is much more about empowerment than recovery,” she explained, emphasizing that “writing was the best way to process trauma.”

Despite her struggles with addiction, Hawkins managed to recover. However, she emphasizes that this recovery is deeply intertwined with her spiritual connection to nature. An illustrative instance of Hawkins’ engagement with nature occurred during the COVID pandemic.

Following an impulse that many of us have entertained, she bought a van and chose to live amidst the trees. It was during this period that Hawkins composed the music for her second EP, titled “Lead with Love.”

In many ways, Hawkins deep spiritual connection to nature has been profoundly shaped by her extensive travels. Born in San Diego, spending her formative years in Massachusetts, and later moving to Tennessee before returning to Southern California, she has broadened her interests and exposed herself to the diverse musical landscapes across America.

“Music is the only thing I have left,” Hawkins confides to the Blade, highlighting the integral role that music has in her life. This intimate relationship with music is evident in her sultry and dynamic compositions. Rather than imitating or copying other artists, Hawkins effortlessly integrates sounds from some of her favorite musical influences to create something new. Some of these influences include LP, Lucinda Williams, Lana Del Rey, and, of course, Amy Winehouse, among others.

Hawkins has always been passionate about music—-she began with piano at a young age, progressed to guitar, and then to bass, eagerly exploring any instrument she could get her hands on. However, instead of following a traditional path of formalized lessons and structured music theory, Hawkins told the Blade that she “has a hard time following directions and being told what to do.”

This independent approach has led her to experiment with various genres and even join unexpected groups, such as a tribute band for Eric Clapton and Cream. While she acknowledges that her eclectic musical interests might be attributed to ADHD, she holds a different belief: “Creative minds like to move around.”

When discussing her latest musical release — “Stay True (the live album)” which was recorded in a live studio setting — Hawkins describes the experience as a form of improvisation with both herself and the band:

“[The experience] was this divine honey that was flowing through all of us.” She explains that this live album was uncertain in the music’s direction. “For a couple of songs,” Hawkins recalls, “we intuitively closed them out.” By embracing creative spontaneity and refusing to be constrained by fear of mistakes, the live album authentically captures raw sound, complete with background chatter, extended outros, and an extremely somber cover of Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train” coupled with a slow piano and accompanied strings.

While “Stay True” was a rewarding experience for Hawkins, her favorite live performance took place in an unexpected location—an unattended piano in the middle of an airport. As she began playing Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata”, Hawkins shared with the Blade a universal connection we all share with music: “This little girl was dancing as I was playing.”

After the performance, tears welled in Hawkins’ eyes as she was touched by the young girl’s appreciation of her musicianship. Hawkins tells the Blade, “It’s not about playing to an audience—it’s about finding your people.”

What sets Hawkins apart as an artist is her ability to connect with her audience in diverse settings. She highlights EDC, an electronic dance music festival, as a place where she unabashedly lets her “freak flag” fly and a place to connect with her people. Her affinity for electronic music not only fuels her original pop music creations, but also inspires her to reinterpret songs with an electronic twist. A prime example of this is with her electronic-style cover of Tal Bachman’s 90’s hit, “She’s So High.”

As an openly queer woman in the music industry, Hawkins is on a mission to safeguard artistic integrity. In songs like “My Father’s Men,” she bares her vulnerability and highlights the industry’s misogyny, which often marginalizes gender minorities in their pursuit of artistic expression.

She confides to the Blade, “The industry can be so sexist, misogynist, and oppressive,” and points out that “there are predators in the industry.” Yet, rather than succumbing to apathy, Hawkins is committed to advocating for gender minorities within the music industry.

“Luckily, people are rising up against misogyny, but it’s still there. ‘My Father’s Men’ is a message: It’s time for more people who aren’t just white straight men to have a say.”

Hawkins is also an activist for other causes, with a fervent belief in the preservation of bodily autonomy. Her self-directed music video “I’ll play Daddy,” showcases the joy of embracing one’s body with Hawkins being sensually touched by a plethora of hands. While the song, according to Hawkins, “fell upon deaf ears in the south,” it hasn’t stopped Hawkins from continuing to fight for the causes she believes in. In her interview, Hawkins encapsulated her political stance by quoting an artist she admires:

“To quote Pink, ‘I don’t care about your politics, I care about your kids.’”

When Hawkins isn’t writing music or being a champion for various causes, you might catch her doing the following: camping, rollerblading, painting, teaching music lessons, relaxing with Bernie (her beloved dog), stripping down for artsy photoshoots, or embarking on a quest to find the world’s best hollandaise sauce.

But at the end of the day, Hawkins sums up her main purpose: “To come together with like-minded people and create.”

Part of this ever-evolving, coming-of-age-like journey includes an important element: plant-based medicine. Hawkins tells the Blade that she acknowledges her previous experience with addiction and finds certain plants to be useful in her recovery:

“The recovery thing is tricky,” Hawkins explains, “I don’t use opiates—-no powders and no pills—but I am a fan of weed, and I think psilocybin can be helpful when used at the right time.” She emphasizes the role of psychedelics in guiding her towards her purpose. “Thanks for psychedelics, I have a reignited sense of purpose … Music came naturally to me as an outlet to heal.”

While she views the occasional dabbling of psychedelics as a spiritual practice, Hawkins also embraces other rituals, particularly those she performs before and during live shows. “I always carry two rocks with me: a labradorite and a tiger’s eye marble,” she explains.

a&e features

Lavender Mass and the art of serious parody in protest

Part 3 of our series on the history of LGBTQ religion in D.C.

(Editor’s note: Although there has been considerable scholarship focused on LGBTQ community and advocacy in D.C., there is a deficit of scholarship focused on LGBTQ religion in the area. Religion plays an important role in LGBTQ advocacy movements, through queer-affirming ministers and communities, along with queer-phobic churches in the city. This is the final installment of a three-part series exploring the history of religion and LGBTQ advocacy in Washington, D.C. Visit our website for the previous installments.)

Six sisters gathered not so quietly in Marion Park, Washington, D.C. on Saturday, October 8, 2022. As the first sounds of the Women’s March rang out two blocks away at 11 am, the Sisters passed out candles to say Mass on the grass. It was their fifth annual Lavender Mass, but this year’s event in particular told an interesting story of religious reclamation, reimagining a meaningful ritual from an institution that seeks to devalue and oppress queer people.

The D.C. Sisters are a chapter of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, an organization of “drag nuns” ministering to LGBTQ+ and other marginalized communities. What first began as satire on Easter Sunday 1979 when queer men borrowed and wore habits from a production of The Sound of Music became a national organization; the D.C. chapter came about relatively late, receiving approval from the United Nuns Privy Council in April 2016. The D.C. Sisters raise money and contribute to organizations focused on underserved communities in their area, such as Moveable Feast and Trans Lifeline, much like Anglican and Catholic women religious orders.

As Sister Ray Dee O’Active explained, “we tend to say we raise funds, fun, and hell. I love all three. Thousands of dollars for local LGBTQ groups. Pure joy at Pride parades when we greet the next generation of activists. And blatant response to homophobia and transphobia by protest after protest.” The Lavender Mass held on October 8th embodied their response to transphobia both inside and outside pro-choice groups, specifically how the overturn of Roe v. Wade in June 2022 intimately affects members of the LGBTQ+ community.

As a little history about the Mass, Sister Mary Full O’Rage, shown wearing a short red dress and crimson coronet and veil in the photo above developed the Lavender Mass as a “counterpart” or “counter narrative” to the Red Mass, a Catholic Mass held the first Sunday of October in honor Catholics in positions of civil authority, like the Supreme Court Justices. The plan was to celebrate this year’s Lavender Mas on October 1st at the Nuns of the Battlefield Memorial, located right across the street from the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle, where many Supreme Court Justices attend the Red Mass every year.

As Sister Mary explained, this year “it was intended to be a direct protest of the actions of the Supreme Court, in significant measure their overturning of reproductive rights.”

Unfortunately, the October 1st event was canceled due to heavy rain and postponed to October 8th at the recommendation of Sister Ruth Lisque-Hunt and Sister Joy! Totheworld. The focus of the Women’s March this year aligned with the focus of the Lavender Mass—reproductive rights—and this cause, Sister Mary explained, “drove us to plan our Lavender Mass as a true counter-ritual and protest of the Supreme Court of who we expected to attend the Red Mass,” and who were protested in large at the Women’s March.

The “Lavender Mass was something that we could adopt for ourselves,” Sister Mary spoke about past events. The first two Masses took place at the Lutheran Church of the Reformation, right around the corner from the Supreme Court. The second Mass, as Sister Mary explained, celebrated Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg; “we canonized her.” Canonization of saints in the Catholic Church also takes place during a Mass, a Papal Mass in particular.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Sisters moved the Mass outside for safety, and the third and fourth Masses were celebrated at the Nuns of the Battlefield Memorial. “It celebrates nuns, and we are nuns, psycho-clown nuns,” Sister Mary chuckled, “but we are nuns.” After the Mass, the Sisters would gather at a LGBTQ+ safe space or protest at the Catholic Church or Supreme Court. Although they often serve as “sister security” at local events, working to keep queer community members safe according to Sister Amore Fagellare, the Lavender Mass is not widely publicly advertised, out of concern for their own.

On October 8th, nine people gathered on the grass in a circle—six sisters, myself, and two people who were close with professed members—as Sister Mary called us to assemble before leading us all in chanting the chorus to Sister Sledge’s 1979 classic song “We Are Family.”

Next, novice Sister Sybil Liberties set a sacred space, whereby Sister Ruth and Sister Tearyn Upinjustice walked in a circle behind us, unspooling pink and blue ribbons to tie us together as a group. As Sister Sybil explained, “we surround this sacred space in protection and sanctify it with color,” pink for the choice to become a parent and blue for the freedom to choose not to be a parent but also as Sybil elaboration, in recognition of “the broad gender spectrum of people with the ability to become pregnant.” This intentional act was sought to fight transphobia within the fight for reproductive rights.

After singing Lesley Gore’s 1963 song “You Don’t Own Me,” six speakers began the ritual for reproductive rights. Holding out our wax plastic candles, Sister Sybil explained that each speaker would describe a story or reality connected to reproductive rights, and “as I light a series of candles for the different paths we have taken, if you recognize yourself in one of these prayers, I invite you to put your hand over your heart, wherever you are, and know that you are not alone – there is someone else in this gathered community holding their hand over their heart too.”

The Sisters went around the circle lighting a candle for those whose stories include the choice to end a pregnancy; those whose include the unwanted loss of a pregnancy or struggles with fertility; those whose include the choice to give birth, raise or adopt a child; those whose include the choice not to conceive a child, to undergo forced choice, or with no choice at all; those who have encountered violence where there “should have been tenderness and care;” and those whose reproductive stories are still being written today.

After each reading, the group spoke together, “may the beginnings and endings in our stories be held in unconditional love and acceptance,” recalling the Prayer of the Faithful or General Intercessions at Catholic Masswhere congregations respond “Lord, hear our prayer” to each petition. Sister Sybil closed out the ritual as Sister Mary cut the blue and pink ribbons between each person, creating small segments they could take away with them and tie to their garments before walking to the Women’s March. The Sisters gathered their signs, drums, and horns before walking to Folger Park together into the crowd of protestors.

At first glance, the Lavender Mass may appear like religious appropriation, just as the Sisters themselves sometimes look to outsiders. They model themselves after Angelican and Catholic women religious, in dress—they actively refer to their clothing as “habits,” their organization—members must also go through aspirant, postulant, and novice stages to be fully professed and they maintain a hierarchical authority, and in action. Like white and black habits, the Sisters all wear white faces to create a unified image and colorful coronets, varying veil color based on professed stage. Sister Allie Lewya explained at their September 2022 meeting, “something about the veils gives us a lot of authority that is undue,” but as the Sisters reinforced at the Women’s March, they are not cosplayers nor customers, rather committed clergy.

As such, the Sisters see their existence within the liminal spaces between satire, appropriation, and reimagination, instead reclaiming the basis of religious rituals to counter the power holders of this tradition, namely, to counter the Catholic Church and how it celebrates those in positions of authority who restrict reproductive rights. Similarly, the Lavender Mass is modeled after a Catholic or Anglican Mass. It has an intention, namely reproductive rights, a call to assemble, setting of a sacred space, song, chant, and prayer requests. It even uses religious terminology; each section of the Mass is ended with a “may it be/Amen/Awen/Ashay/aho.”

While this ritual—the Lavender Mass—appropriates a religious ritual of the Catholic Church and Anglican Church, this religious appropriation is necessitated by exclusion and queerphobia. As David Ford explains in Queer Psychology, many queer individuals retain a strong connection to their faith communities even though they have experienced trauma from these same communities. Jodi O’Brien builds on this, characterizing Christian religious institutions as spaces of personal meaning making and oppression. This essay further argues that the fact this ritual is adopted and reimagined by a community that the dominant ritual holder—the Catholic Church—oppressed and marginalized, means that it is not religious appropriation at all.

Religious appropriation, as highlighted in Liz Bucar’s recent book, Stealing My Religion (2022), is the acquisition or use of religious traditions, rituals, or objects without a full understanding of the community for which they hold meaning. The Sisters, however, fully understand the implications of calling themselves sisters and the connotations of performing a ritual they call a “Mass” as women religious, a group that do not have this authority in the Catholic Church. It is the reclamation of a tradition that the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence understand because some were or are part of the Catholic Church.

Some sisters still seek out spiritual meaning, but all also recognize that the Catholic Church itself is an institution that hinders their sisters’ access and actively spreads homophobia and transphobia to this day. As such, through the Lavender Mass, the sisters have reclaimed the Mass as a tool of rebellion in support of queer identity.

Just as the Sisters recognize the meaning and power of the ritual of a Mass, along with the connotations of being a sister, the Lavender Mass fulfilled its purpose as a ritual of intention just as the Sisters fulfill public servants. “As a sister,” Sister Ruth dissected, “as someone who identifies as a drag nun, it perplexes people, but when you get the nitty gritty, we serve a similar purpose, to heal a community, to provide support to a community, to love a community that has not been loved historically in the ways that it should be loved.

The Sisters’ intentionality in recognizing and upholding the role of a woman religious in their work has been well documented as a serious parody for the intention of queer activism by Melissa Wilcox. The Lavender Mass is a form of serious parody, as Wilcox posits in the book: Queer Nuns: Religion, Activism, and Serious Parody(2018). The Mass both challenges the queerphobia of the Catholic Church while also reinforcing the legitimacy of this ritual as a Mass. The Sisters argue that although they would traditionally be excluded from religious leadership in the Catholic Church, they can perform a Mass. In doing so, they challenge the role that women religious play in the Catholic Church as a whole and the power dynamics that exclude queer communities from living authentically within the Church.

By reclaiming a tradition from a religious institution that actively excludes and traumatizes the LGBTQ+ community, the Lavender Mass is a form of religious reclamation in which an oppressed community cultivates queer religious meaning, reclaims a tradition from which they are excluded, and uses it to fuel queer activism (the fight for reproductive rights). This essay argues that the Lavender Mass goes one step further than serious parody. While the Sisters employ serious parody in their religious and activist roles, the Lavender Mass is the active reclamation of a religious tradition for both spiritual and activist ends.

Using the celebration of the Mass as it was intended, just within a different lens for a different purpose, this essay argues, is religious reclamation. As a collection of Austrian and Aotearoan scholars explored most recently in a chapter on acculturation and decolonization, reclamation is associated with the reassertion and ownership of tangibles: of rituals, traditions, objects, and land. The meaning of the Lavender Mass comes not only from the Sisters’ understanding of women religious as a social and religious role but rather from the reclamation of a physical ritual—a Mass—that has specific religious or spiritual meaning for the Sisters.

When asked why it was important to call this ritual a “Mass,” Sister Mary explained: “I think we wanted to have something that denoted a ritual, that was for those who know, that the name signifies that it was a counter-protest. And you know, many of the sisters grew up with faith, not all of them Catholics but some, so I think ‘Mass’ was a name that resonated for many of us.”

As Sister Ray said, “my faith as a queer person tends to ostracize me but the Sisters bring the imagery and language of faith right into the middle of the LGBTQ world.” This Lavender Mass, although only attended and experienced by a few of the Women’s March protests, lived up to its goal as “a form of protest that is hopefully very loud,” as Sister Millie Taint advertised in the Sisters’ September 2022 chapter meeting. It brought religious imagery and language of faith to a march for reproductive rights, using a recognized model of ritual to empower protestors.

The Lavender Mass this year, as always, was an act of rebellion, but by situating itself before the Women’s March and focusing its intention for reproductive rights, the Sisters’ reclaimed a religious ritual from a system of authority which actively oppressed LGBTQ+ peoples and those with the ability to become pregnant, namely the Catholic Church, and for harnessing it for personal, political, and spiritual power. In essence, it modelled a system of religious reclamation, by which a marginalized community takes up a religious ritual to make its own meaning and oppose the religious institution that seeks to exclude the community from ritual participation.

Emma Cieslik will be presenting on LGBTQ+ Religion in the Capital at the DC History Conference on Friday, April 6th. She is working with a DC History Fellow to establish a roundtable committed to recording and preserving this vital history. If you have any information about these histories, please reach out to Emma Cieslik at [email protected] or the Rainbow History Project at [email protected].

-

Africa5 days ago

Africa5 days agoCongolese lawmaker introduces anti-homosexuality bill

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoReenactment of first gay rights picket at White House draws interest of tourists

-

District of Columbia1 day ago

District of Columbia1 day agoNew D.C. LGBTQ+ bar Crush set to open April 19

-

World5 days ago

World5 days agoOut in the World: LGBTQ news from Europe and Asia