Miscellaneous

Kameny in context

How will the trailblazer be remembered? And what is his rightful place in the pantheon of gay rights legends?

Frank Kameny among his colleagues in Los Angeles in 1998 to honor Jim Kepner and the 50th anniversary of the gay rights movement. First row from left are Lisa Ben, the late Harry Hay, the late John Burnside, Jose Sarria, the late Del Martin, Phyllis Lyon; (second row) Fred Frisbie, the late Bob Basker, Kameny, Florence Fleischman, the late Hal Call, Robin Tyler; (third row) the late Philip Johnson, Eddie Sandifer, the late Vern Bullough, Malcolm Boyd; (fourth row) the late Barbara Gittings, Kay Tobin Lahusen, the late Jack Nichols, Mark Segal, unidentified; (fifth row) the late Cliff Anchor, Leo Laurence, Eldon Murray, John O’Brien and Jerome Stevens. (Photo by Fred Camerer; reprinted with permission)

News outlets over the past week — both LGBT and mainstream — have reported the death of Frank Kameny, the legendary Washington-based activist universally regarded as one of the most influential pre-Stonewall homophile movement leaders.

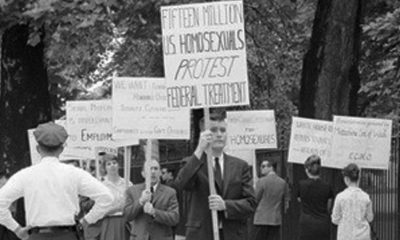

Kameny died Oct. 11 at age 86 at his home in Northwest Washington and the news accounts have relayed oft-noted biographical facts that have taken on increasingly mythic proportions over the years: his firing from the Army Map Service in 1957 for being gay, the 1961 founding of the D.C. Mattachine Society, the “gay is good” slogan he coined, his role in convincing the American Psychiatric Association in 1973 to stop classifying homosexuality as a mental disorder, the Clinton-signed presidential executive order that permitted gay people to be given security clearances, the repeal of D.C.’s anti-sodomy law, his decades of work with the local Gay Activists Alliance (GAA; later GLAA) and more.

But once the dust settles — memorial services are planned for Washington and San Francisco on Nov. 15, the 50th anniversary of the founding of the D.C. Mattachine chapter — what will Kameny’s legacy be? Never one to shy away from taking credit, might his bluster and longevity have created a sense of myth about him? Or could his D.C. home base over so many years (he arrived here in 1956 and never left) have skewed perceptions of his efforts among local activists who may not be aware of the contributions of Kameny’s peers in other cities, especially on the West Coast? And where does Kameny fit in among other pioneering activists of his era? The Blade spoke to several gay historians, Kameny peers — both here and around the country — and friends to find out.

Kameny among peers

Kameny’s World War II-era generation is, of course, reaching its later years and many of the pre-Stonewall homophile activists — legendary figures such as Barbara Gittings, Harry Hay, Del Martin, Jim Foster, Jim Kepner, Jack Nichols and Hal Call — have died.

San Francisco’s Phyllis Lyon, who married her late partner Del Martin in 2008 after more than 50 years of joint activism, says she’s doing well (she’ll be 87 next month), still drives and has “no intention” of leaving her home, though life, obviously, has been a lot different since Martin’s 2008 death, just two months after they got married. She speaks highly of Kameny but admits to being fuzzy on specifics.

“Well, I think he did a lot of very good things, definitely,” she says. “I do remember Frank and I was very sorry to hear that he had died but it was different in those early days. I guess you could say the lesbians and gay men weren’t always buddy buddy buddy buddy back then. We worked together some, but in essence we also worked mostly with our own sexes.”

Things were somewhat different in Washington. Though she eventually moved on and did other things with her life, Lilli Vincenz, 73, was an early Washington-based activist who was in the Mattachine Society here and joined Kameny in his legendary White House protest in April 1965. She also knew — as did Lyon — the late Harry Hay, who started the first Mattachine Society in Los Angeles in 1950, which Kameny regarded as the start of the modern gay rights movement in the U.S. (a 1920s Chicago-based group was quickly shut down by police though a gay “emancipation group” started in 1897 in Berlin and lasted decades before being shut down by Hitler’s Nazi regime).

“Well, they had a slightly different approach,” Vincenz says of Hay and Kameny. “Frank was here taking advantage of Washington and being close to all the big government agencies, so that was his focus.”

Paul Kuntzler, who was just 20 when he met Kameny at the Chicken Hut in early 1962, was always “the kid” of the group. He says, as was Kameny’s contention, that the D.C. Mattachine Society was accomplishing things gays in other U.S. cities — chapters also existed in New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco and Los Angeles at the time — weren’t doing.

“A lot of them were just content to do more research and education,” Kuntzler says. “Originally I thought Harry Hay was very brave and I think originally they were very active, but they kind of got disinvolved.”

Kuntzler says it started with Hay’s group in 1950, the second wave was in Washington in the early ‘60s, then Stonewall, the 1969 New York riots that catapulted gay rights issues into the mainstream consciousness.

In Kuntzler’s estimation, Kameny is “the most influential and most important person in the history of the gay rights movement. The only other person I’d put in that league would be Barbara Gittings who died in February 2007. She was an intellectual heavyweight, but not quite up there with Frank. But she was very powerful and influential.”

San Francisco-based activist Michael Petrelis, who in 2009 launched an effort to have Kameny awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor, agrees. He lived from 1990-1995 in Washington and, though they sometimes clashed on issues of AIDS activism, saw Kameny as a grandfather of sorts.

“Some of my pushy personality, my pushy activism, comes from Frank,” Petrelis says.

Historical assessments

But how does Kameny’s legacy sit with gay historians? Depends whom one asks.

Gay scholar John Lauritsen, who wrote two essays for the 2002 anthology “Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in a Historical Context,” says Kameny should certainly be admired for his contributions but that he was only one type of activist whose efforts should be put in context. Lauritsen, during a phone chat from his Boston home, says he was active in the homophile movement since 1960 and knew Kameny and Gittings in the ‘70s when they would meet at various conferences.

“Our politics were much different,” Lauritsen says. “I was much more radical. But Frank was always friendly to me … I would say I admired Kameny. He was a very good public speaker … but I think one has to give credit to the scholars and Kameny was not a scholar … I think he was more a good publicist perhaps. I’m not sure he really did invent the saying ‘gay is good,’ that’s been debated, but at least it was a catchy slogan and it played a role in the movement at the time.”

Kameny could be a polarizing figure. Though even his detractors in the gay world eventually came to mostly acknowledge his accomplishments, in the early years there was much debate about the appropriate plan to gain traction with the movement.

“In those days, people felt he was rather reckless and far too militant,” says writer David Carter who interviewed Kameny about 45 times over the last several years for a biography he hopes to publish. “It’s funny though, after Stonewall, he was held up as a symbol of not being militant enough but that was more of a caricature of Frank.”

Michael Bronski, whose book “A Queer History of the United States” came out in May, teaches women, gender and LGBT studies at Dartmouth. He praises Kameny’s work but agrees, Kameny wasn’t working alone and it’s important to remember others.

“It’s vitally important to remember Frank and to give him credit for all this, but the ‘50s were really an incredible time … It’s unfair, I agree, to try to rank people mostly, unless the ranking happens by simply looking at the facts, but does the average gay person reading the Advocate really know who Harry Hay was or who Harvey Milk was? They think of Sean Penn or they might say, ‘Harvey Milk, wasn’t he married to Madonna in the ‘80s?’ Not knowing about Frank is a huge loss and it’s a loss that needs to be corrected. But I don’t think this is just an LGBT problem, it’s an American problem in general.”

Bronski is quick to point out, though, that Kameny is part of a small list of pre-Stonewall iconoclasts.

“Harry Hay, Del and Phyllis, Barbara Gittings — there aren’t many whose names come to the forefront because a lot of the work (others) did was very quiet, so somebody like, say, Randy Wicker, who founded the Oscar Wilde bookstore and the Mattachine Society in New York before Stonewall, that was a different kind of a thing.”

Paul Boneberg, executive director of the San Francisco-based GLBT Historical Society, is more unequivocal.

“There is no greater gay activist than Frank Kameny,” Boneberg says. “He is one of the heroic founders of the modern era.”

Boneberg agrees with Bronski — the pre-Stonewall movers and shakers list is quite small.

“He’s part of a very small group,” Boneberg says. “He and a few of the early activists really founded the GLBT movement and the community is what it is because of people like Frank and what’s extraordinary is that his work in the ’50s and ‘60s continued right up until this year. It was really a lifetime of service to the queer community. … What we’re seeing is the passing of the queer community’s greatest generation. That World War II generation that he was part of. He was just an extraordinary individual and it’s a great loss to the community.”

Malcolm Lazin, executive director of the Equality Form and executive producer of the PBS documentary “Gay Pioneers, unequivocally this week called Kameny “the father of the LGBT civil rights movement” in a press release. The term hasn’t been widely used but may become more common as Kameny’s contributions are assessed.

And where might LGBT rights be today if Kameny hadn’t done what he did?

“I think on one level, what Frank did moved us ahead incredibly far,” Bronski says. “But if Frank didn’t exist, would somebody else have done it? Possibly. You know Frank wasn’t the only person to get arrested and lose his job. It’s conceivable and actually likely that somebody else would have had the courage to do that, but in no way do I say that to diminish what he did, but did the movement depend on Frank? I don’t think so. Did Frank move the movement forward? Sure.”

Kameny on Kameny

And what did Kameny himself think of his place in the history books? Outtakes from an Aug. 16 interview pertaining to the push for a presidential Medal of Freedom for him, found him waxing nostalgic for several of his peers.

“Just about all these people are gone,” Kameny said. “One of the first I would name would be Barbara Gittings, whom I miss very, very much. Another would be Jack Nichols. One by one they have all gone.”

Kameny also mentioned several activists whose work has been more D.C.-centric.

“On much less a level, but still someone who goes all the way back would be Craig Howell and coming much later onto the scene and I first got to know him in college in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but I would also say Rick Rosendall. That’s just off the top of my head. Many of them have just all died off one after another and I’m very, very sorry to see some of them go, but that happens.”

Kameny phoned the next morning to say he was “embarrassed I overlooked Paul Kuntzler. He goes back to the very beginning of my involvement in 1961 right after we formed the Mattachine Society … he was perhaps the last one going back to the ‘60s who’s still around.”

Comparing Kameny’s life and work to Harvey Milk’s — the first openly gay man to be elected to public office when he won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors — is apples and oranges, many say. If Milk’s story is more widely known, it’s undoubtedly because it’s been told several times, most memorably, perhaps, in a 2008 Academy Award-winning film. That he died young (he was murdered at age 48) perhaps gave him a JFK-like stature among gays that captured their consciousness.

“They were just from very different times,” Boneberg says. “Harvey is separated almost a whole generation and he would have acknowledged that. … It’s hard for people today to imagine how difficult it was to stand up and be out back then. Time is such a huge factor. That first generation stood alone and said, ‘I will not take this.’ Frank did that. [Drag legend] Jose [Sarria] did that. It’s just something later people have not had to do because there were already other people standing. It’s very hard for people to grasp. There were profound legal consequences and people who were gay were literally destroyed.”

Even Cleve Jones, a friend and contemporary of Milk and an activist in his own right, says their lives are too different to warrant much comparison.

“Harvey and all of us who came after the Stonewall rebellion, all of us were marching down a road that had already been paved by people like Frank, Barbara [Gittings], Phyllis and Del … the Stonewall generation was still in the closet when Frank was doing his work, so you can’t really compare them.”

Choices made

Milk, of course, suffered. But those close to him say Kameny suffered in other ways — less dramatic, but also difficult.

“He lived in poverty,” Kuntzler says. “He got some inheritance money from his mother and he eventually bought [his] house, but it was a struggle. I gave him money for his fax machine. People helped him out, but he lived basically in poverty, there’s no question about it.”

Marvin Carter, a local gay volunteer with Helping Our Brothers and Sisters who’d known Kameny for years, started helping him the winter before last during several extreme blizzards the region suffered.

“There’d been a few calls here and there before, but that’s when we really started to see the extent of the situation,” Carter says. “He was snowed in and had no groceries. … It was really a bad situation.”

But was some of that by choice? Obviously in recent years Kameny was elderly, but why didn’t he work much — at least for income — in the ‘70s and ‘80s? Couldn’t he have secured a position doing the work he loved for an organization like Human Rights Campaign or National Gay & Lesbian Task Force?

Kuntzler says Kameny was “very stubborn” and single minded in his activist philosophies.

“He was very independent, very much his own person. It would have been very hard for him to acquiesce to someone else’s vision,” Kuntzler says. “He absolutely sacrificed.”

Bronski agrees, but with a caveat.

“Yes, he made that sacrifice, but it’s important to remember that he made it on his own. There wasn’t a vote on it. We should all be thankful and we can’t expect other people to do the same. It’s a matter of self sacrifice, but yes, from what I’ve heard he did actually live in fairly impoverished conditions.”

Time, of course, has a way of putting individuals’ contributions into perspective. In the meantime, Kameny’s colleagues are remembering him fondly.

“In my opinion, his legacy is already established,” Vincenz says. “He was a tutor to me and I was very thrilled to work with him. … I saw him as a zealot, very effective. He also had such a kind heart. I was reading not long ago his lovely eulogy to Barbara and it was just beautiful.”

Kuntzler remembers a rabble-rouser who “delighted in antagonizing.”

“He was never violent, it was all intellectual,” he says. “And he was very self assured. He didn’t question it at all. He truly felt that he was right and they were all wrong.”

Miscellaneous

LA-based TransLatin@ Coalition leads in time of attacks

Members of Congress ‘calling us a radical organization’

As ICE raids intensify across Southern California and anti-immigrant sentiment resurfaces in Orange County, transgender and immigrant communities are once again being targeted. These crackdowns go beyond enforcement — they’re designed to instill fear. At the same time, a coordinated right-wing smear campaign is attempting to discredit the very organizations working to keep these communities safe.

Last month, the TransLatin@ Coalition, a cornerstone in the fight for trans, queer, and immigrant rights in Los Angeles, was publicly named by members of Congress. But this was no recognition. It was a calculated attack.

“They’re calling us a radical organization,” said Bamby Salcedo, president and CEO of the TransLatin@ Coalition. “They’re spreading lies, saying we’re using government funding to abolish ICE and the police and to provide abortion access. We do believe in those things, but the funding we receive is used to serve our people.”

Now, that funding is being stripped away.

In the face of state violence, political backlash, and economic sabotage, TLC is responding the way it always has: by organizing, celebrating, and building a better world. Because when our communities are under attack, we show up — stronger, louder, and more united than ever.

Salcedo, herself a proud trans Latina immigrant, has spent decades fighting for those living at the margins. “I always say I am an intersection walking,” she said with a smile. “Our organization is made up of the people most impacted — and we are the ones leading the work.”

In Los Angeles County, roughly one-third of residents are immigrants, the majority of whom are Latino. Unsurprisingly, trans Latinas represent the largest segment within the local trans community.

Yet even within immigrant justice spaces, trans people are often sidelined.

“It’s a very hetero-centric space,” Salcedo said. “Most of the time, they don’t even consider the lives and experiences of trans and queer immigrants.”

The TransLatin@ Coalition is actively changing that. As a key member of a broad alliance of more than 100 immigrant-serving organizations across Los Angeles, including CHIRLA and the Filipino Workers Center, the TransLatin@ Coalition helped secure over $160 million in American Rescue Plan funds for immigrant housing, internet access, and legal services.

They also co-created the groundbreaking TGIE (Transgender, Gender-Nonconforming, Intersex Empowerment) initiative, which allocates $7 million in Los Angeles County’s annual budget to support trans-led service providers.

“We don’t just want symbolic policies,” said Salcedo. “We fight for resources. We analyze the budget. We make it real.”

Despite these victories, the TransLatin@ Coalition is now confronting devastating federal cuts.

“Our work has been defunded,” Salcedo said bluntly. “Multiple programs are gone. And we’re not alone — trans-led organizations across the country, especially in the South, are facing the same.”

She pointed to a broader backlash against anything associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). “The private sector is pulling back. Philanthropy is scared. Even the same corporations that fund us during Pride are investing in our opposition the rest of the year. It’s hypocrisy.”

Rather than retreat, the TransLatin@ Coalition is calling for bold, collective action.

“Now’s the time for people to step up,” said Salcedo. “We have the strategy. We’re doing the work. But we need resources — and we need real solidarity, not just statements.”

To respond to the crisis and raise urgently needed funds, the TransLatin@ Coalition is organizing its Walk for Humanity on Saturday, Aug. 24. The event will begin at 9 a.m. in Silver Lake and march to Sunset and Western, featuring live performances, a resource fair, and a unified call for justice.

And yes — it will be joyful.

“This is a call for all people to stand in solidarity with one another,” said Salcedo. “We want to bring together 1,000 people, each raising $1,000. It’s going to be a beautiful day of community and resistance.”

In a surprise announcement, Salcedo also revealed she will debut her first single — a cumbia track inspired by the movement. “It’s about movement in both senses: our political movement, and moving our bodies,” she laughed. “We can’t let them take away our joy. Joy is how we survive.”

When asked what more local leaders can do, Salcedo didn’t hesitate. “Elected officials are public servants. That means serving all people,” she said. “We may be a small population, but we are deeply impacted — and we contribute so much to this city.”

She pointed to data from LA’s most recent homelessness count, which identified over 2,000 trans and gender-expansive people experiencing homelessness. That number exists thanks in large part to years of advocacy demanding the city count and name trans lives. “We have the data now. There’s no excuse not to invest in our people.”

She also uplifted allies like Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath and newly appointed City Council member Isabel Urado, the first openly LGBTQ person to hold her seat. “They’ve seen our work and are fighting to invest in it,” Salcedo said. “We’re hopeful we’ll see another $10 million in city funding. But we need the community behind us.”

At the end of our conversation, I asked Salcedo what she would say to undocumented, queer, and trans Angelenos who are feeling afraid right now.

Her answer was clear, powerful, and full of love:

“You are a divine creation. You deserve to exist in this world. Walk your path with dignity, love, and respect — for yourself and for others. You belong. You are part of me. You are part of us.”

If standing with trans immigrants, resisting federal rollbacks, and dancing in the streets sounds like your kind of solidarity, join the TransLatin@ Coalition on Aug. 24. Because when we show up together, we protect each other. And when we dance together — we win.

Watch the full interview with Salcedo:

Miscellaneous

LGBTQ cruise ship rescues 11 migrants between Cuba and Mexico

Rescue took place in Yucatán Channel on Wednesday

A cruise ship chartered by an LGBTQ travel company on Wednesday rescued 11 Cubans from a boat that was adrift between their country and Mexico.

Vacaya in a press release said the Royal Caribbean’s Brilliance of the Seas, which had left from New Orleans, discovered the migrants’ boat in the Yucatán Channel, a strait between Mexico and Cuba that connects the Gulf of Mexico (the Trump-Vance administration now refers to the body of water as the Gulf of America) and the Caribbean Sea.

A video that Vacaya provided shows the migrants’ boat before the rescue. Other videos show the rescue taking place.

MTV’s Downtown Julie Brown, who was performing on the ship, described the rescue in a video she posted to social media.

“We are in the middle of a live rescue operation right now,” she said. “The captain of the ship, while we were hauling so fast the other way, thought he saw a boat in distress. So, we looped around … and it was indeed a boat in distress.”

“Nothing speaks more to VACAYA’s values than providing comfort in a moment of need,” said Vacaya CEO Randle Roper in the press release. “I’m so happy we were able to bring these 11 refugees onboard safely and provide medical care, dry clothes, food, and, most importantly, water.”

“It’s sad that some people have to put themselves through such trauma in hopes of finding a better life, but that’s where we are today,” added Roper. “I’m so proud of our LGBT+ guests rallying to collect clothes for these fellow humans in need.”

The ship is scheduled to return to New Orleans on Saturday.

Miscellaneous

The dedicated life and tragic death of gay publisher Troy Masters

‘Always working to bring awareness to causes larger than himself’

Troy Masters was a cheerleader. When my name was called as the Los Angeles Press Club’s Print Journalist of the Year for 2020, Troy leapt out of his seat with a whoop and an almost jazz-hand enthusiasm, thrilled that the mainstream audience attending the Southern California Journalism Awards gala that October night in 2021 recognized the value of the LGBTQ community’s Los Angeles Blade.

That joy has been extinguished. On Wednesday, Dec. 11, after frantic unanswered calls from his sister Tammy late Monday and Tuesday, Troy’s longtime friend and former partner Arturo Jiminez did a wellness check at Troy’s L.A. apartment and found him dead, with his beloved dog Cody quietly alive by his side. The L.A. Coroner determined Troy Masters died by suicide. No note was recovered. He was 63.

Considered smart, charming, committed to LGBTQ people and the LGBTQ press, Troy’s inexplicable suicide shook everyone, even those with whom he sometimes clashed.

Troy’s sister and mother – to whom he was absolutely devoted – are devastated. “We are still trying to navigate our lives without our precious brother/son. I want the world to know that Troy was loved and we always tried to let him know that,” says younger sister Tammy Masters.

Tammy was 16 when she discovered Troy was gay and outed him to their mother. A “busy-body sister,” Tammy picked up the phone at their Tennessee home and heard Troy talking with his college boyfriend. She confronted him and he begged her not to tell.

“Of course, I ran and told Mom,” Tammy says, chuckling during the phone call. “But she – like all mothers – knew it. She knew it from an early age but loved him unconditionally; 1979 was a time [in the Deep South] when this just was not spoken of. But that didn’t stop Mom from being in his corner.”

Mom even marched with Troy in his first Gay Pride Parade in New York City. “Mom said to him, ‘Oh, my! All these handsome men and not one of them has given me a second look! They are too busy checking each other out!” Tammy says, bursting into laughter. “Troy and my mother had that kind of understanding that she would always be there and always have his back!

“As for me,” she continues, “I have lost the brother that I used to fight for in any given situation. And I will continue to honor his cause and lifetime commitment to the rights and freedom for the LGBTQ community!”

Tammy adds: “The outpouring of love has been comforting at this difficult time and we thank all of you!”

No one yet knows why Troy took his life. We may never know. But Troy and I often shared our deeply disturbing bouts with drowning depression. Waves would inexplicitly come upon us, triggered by sadness or an image or a thought we’d let get mangled in our unresolved, inescapable past trauma.

We survived because we shared our pain without judgment or shame. We may have argued – but in this, we trusted each other. We set everything else aside and respectfully, actively listened to the words and the pain within the words.

Listening, Indian philosopher Krishnamurti once said, is an act of love. And we practiced listening. We sought stories that led to laughter. That was the rope ladder out of the dark rabbit hole with its bottomless pit of bullying and endless suffering. Rung by rung, we’d talk and laugh and gripe about our beloved dogs.

I shared my 12 Step mantra when I got clean and sober: I will not drink, use or kill myself one minute at a time. A suicide survivor, I sought help and I urged him to seek help, too, since I was only a loving friend – and sometimes that’s not enough.

(If you need help, please reach out to talk with someone: call or text 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. They also have services in Spanish and for the deaf.)

In 2015, Troy wrote a personal essay for Gay City News about his idyllic childhood in the 1960s with his sister in Nashville, where his stepfather was a prominent musician. The people he met “taught me a lot about having a mission in life.”

During summers, they went to Dothan, Ala., to hang out with his stepfather’s mother, Granny Alabama. But Troy learned about “adult conversation — often filled with derogatory expletives about Blacks and Jews” and felt “my safety there was fragile.”

It was a harsh revelation. “‘Troy is a queer,’ I overheard my stepfather say with energetic disgust to another family member,” Troy wrote. “Even at 13, I understood that my feelings for other boys were supposed to be secret. Now I knew terror. What my stepfather said humiliated me, sending an icy panic through my body that changed my demeanor and ruined my confidence. For the first time in my life, I felt depression and I became painfully shy. Alabama became a place, not of love, not of shelter, not of the magic of family, but of fear.”

At the public pool, “kids would scream, ‘faggot,’ ‘queer,’ ‘chicken,’ ‘homo,’ as they tried to dunk my head under the water. At one point, a big crowd joined in –– including kids I had known all my life –– and I was terrified they were trying to drown me.

“My depression became dangerous and I remember thinking of ways to hurt myself,” Troy wrote.

But Troy Masters — who left home at 17 and graduated from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville — focused on creating a life that prioritized being of service to his own intersectional LGBTQ people. He also practiced compassion and last August, Troy reached out to his dying stepfather. A 45-minute Facetime farewell turned into a lovefest of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Troy discovered his advocacy chops as an ad representative at the daring gay and lesbian activist publication Outweek from 1989 to 1991.

“We had no idea that hiring him would change someone’s life, its trajectory and create a lifelong commitment” to the LGBTQ press, says Outweek’s co-founder and former editor-in-chief Gabriel Rotello, now a TV producer. “He was great – always a pleasure to work with. He had very little drama – and there was a lot of drama at Outweek. It was a tumultuous time and I tended to hire people because of their activism,” including Michelangelo Signorile, Masha Gessen, and Sarah Pettit.

Rotello speculates that because Troy “knew what he was doing” in a difficult profession, he was determined to launch his own publication when Outweek folded. “I’ve always been very happy it happened that way for Troy,” Rotello says. “It was a cool thing.”

Troy and friends launched NYQ, renamed QW, funded by record producer and ACT UP supporter Bill Chafin. QW (QueerWeek) was the first glossy gay and lesbian magazine published in New York City featuring news, culture, and events. It lasted for 18 months until Chafin died of AIDS in 1992 at age 35.

The horrific Second Wave of AIDS was peaking in 1992 but New Yorkers had no gay news source to provide reliable information at the epicenter of the epidemic.

“When my business partner died of AIDS and I had to close shop, I was left hopeless and severely depressed while the epidemic raged around me. I was barely functioning,” Troy told VoyageLA in 2018. “But one day, a friend in Moscow, Masha Gessen, urged me to get off my back and get busy; New York’s LGBT community was suffering an urgent health care crisis, fighting for basic legal rights and against an increase in violence. That, she said, was not nothing and I needed to get back in the game.”

It took Troy about two years to launch the bi-weekly newspaper LGNY (Lesbian and Gay New York) out of his East Village apartment. The newspaper ran from 1994 to 2002 when it was re-launched as Gay City News with Paul Schindler as co-founder and Troy’s editor-in-chief for 20 years.

“We were always in total agreement that the work we were doing was important and that any story we delved into had to be done right,” Schindler wrote in Gay City News.

Though the two “sometimes famously crossed swords,” Troy’s sudden death has special meaning for Schindler. “I will always remember Troy’s sweetness and gentleness. Five days before his death, he texted me birthday wishes with the tag, ‘I hope you get a meaningful spanking today.’ That devilishness stays with me.”

Troy had “very high EI (Emotional Intelligence), Schindler says in a phone call. “He had so much insight into me. It was something he had about a lot of people – what kind of person they were; what they were really saying.”

Troy was also very mischievous. Schindler recounts a time when the two met a very important person in the newspaper business and Troy said something provocative. “I held my breath,” Schindler says. “But it worked. It was an icebreaker. He had the ability to connect quickly.”

The journalistic standard at LGNY and Gay City News was not a question of “objectivity” but fairness. “We’re pro-gay,” Schindler says, quoting Andy Humm. “Our reporting is clear advocacy yet I think we were viewed in New York as an honest broker.”

Schindler thinks Troy’s move to Los Angeles to jump-start his entrepreneurial spirit and reconnect with Arturo, who was already in L.A., was risky. “He was over 50,” Schindler says. “I was surprised and disappointed to lose a colleague – but he was always surprising.”

“In many ways, crossing the continent and starting a print newspaper venture in this digitally obsessed era was a high-wire, counter-intuitive decision,” Troy told VoyageLA. “But I have been relentlessly determined and absolutely confident that my decades of experience make me uniquely positioned to do this.”

Troy launched The Pride L.A. as part of the Mirror Media Group, which publishes the Santa Monica Mirror and other Westside community papers. But on June 12, 2016, the day of the Pulse Nightclub shooting in Orlando, Fla., Troy said he found MAGA paraphernalia in a partner’s office. He immediately plotted his exit. On March 10, 2017, Troy and the “internationally respected” Washington Blade announced the launch of the Los Angeles Blade.

In a March 23, 2017 commentary promising a commitment to journalistic excellence, Troy wrote: “We are living in a paradigm shifting moment in real time. You can feel it. Sometimes it’s overwhelming. Sometimes it’s toxic. Sometimes it’s perplexing, even terrifying. On the other hand, sometimes it’s just downright exhilarating. This moment is a profound opportunity to reexamine our roots and jumpstart our passion for full equality.”

Troy tried hard to keep that commitment, including writing a personal essay to illustrate that LGBTQ people are part of the #MeToo movement. In “Ending a Long Silence,” Troy wrote about being raped at 14 or 15 by an Amtrak employee on “The Floridian” traveling from Dothan, Ala., to Nashville.

“What I thought was innocent and flirtatious affection quickly turned sexual and into a full-fledged rape,” Troy wrote. “I panicked as he undressed me, unable to yell out and frozen by fear. I was falling into a deepening shame that was almost like a dissociation, something I found myself doing in moments of childhood stress from that moment on. Occasionally, even now.”

From the personal to the political, Troy Masters tried to inform and inspire LGBTQ people.

Richard Zaldivar, founder and executive director of The Wall Las Memorias Project, enjoyed seeing Troy at President Biden’s Pride party at the White House.

“Just recently he invited us to participate with the LA Blade and other partners to support the LGBTQ forum on Asylum Seekers and Immigrants. He cared about underserved community. He explored LGBTQ who were ignored and forgotten. He wanted to end HIV; help support people living with HIV but most of all, he fought for justice,” Zaldivar says. “I am saddened by his loss. His voice will never be forgotten. We will remember him as an unsung hero. May he rest in peace in the hands of God.”

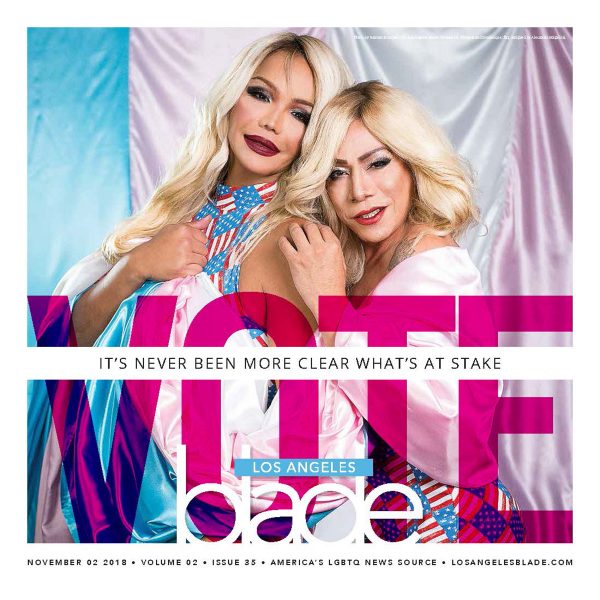

Troy often featured Bamby Salcedo, founder, president/CEO of TransLatina Coalition, and scores of other trans folks. In 2018, Bamby and Maria Roman graced the cover of the Transgender Rock the Vote edition.

“It pains me to know that my dear, beautiful and amazing friend Troy is no longer with us … He always gave me and many people light,” Salcedo says. “I know that we are living in dark times right now and we need to understand that our ancestors and transcestors are the one who are going to walk us through these dark times… See you on the other side, my dear and beautiful sibling in the struggle, Troy Masters.”

“Troy was immensely committed to covering stories from the LGBTQ community. Following his move to Los Angeles from New York, he became dedicated to featuring news from the City of West Hollywood in the Los Angeles Blade and we worked with him for many years,” says Joshua Schare, director of Communications for the City of West Hollywood, who knew Troy for 30 years, starting in 1994 as a college intern at OUT Magazine.

“Like so many of us at the City of West Hollywood and in the region’s LGBTQ community, I will miss him and his day-to-day impact on our community.”

(Photo by Richard Settle for the City of West Hollywood)

“Troy Masters was a visionary, mentor, and advocate; however, the title I most associated with him was friend,” says West Hollywood Mayor John Erickson. “Troy was always a sense of light and working to bring awareness to issues and causes larger than himself. He was an advocate for so many and for me personally, not having him in the world makes it a little less bright. Rest in Power, Troy. We will continue to cause good trouble on your behalf.”

Erickson adjourned the WeHo City Council meeting on Monday in his memory.

Masters launched the Los Angeles Blade with his partners from the Washington Blade, Lynne Brown, Kevin Naff, and Brian Pitts, in 2017.

“Troy’s reputation in New York was well known and respected and we were so excited to start this new venture with him,” says Naff. “His passion and dedication to queer LA will be missed by so many. We will carry on the important work of the Los Angeles Blade — it’s part of his legacy and what he would want.”

AIDS Healthcare Foundation President Michael Weinstein, who collaborated with Troy on many projects, says he was “a champion of many things that are near and dear to our heart,” including “being in the forefront of alerting the community to the dangers of Mpox.”

“All of who he was creates a void that we all must try to fill,” Weinstein says. “His death by suicide reminds us that despite the many gains we have made, we’re not all right a lot of the time. The wounds that LGBT people have experienced throughout our lives are yet to be healed even as we face the political storm clouds ahead that will place even greater burdens on our psyches.”

May the memory and legacy of Troy Masters be a blessing.

Veteran LGBTQ journalist Karen Ocamb served as the news editor and reporter for the Los Angeles Blade.