Opinions

Why do black gay celebs have white partners?

Sam, Roberts, Collins, Sykes and more in a sea of whiteness

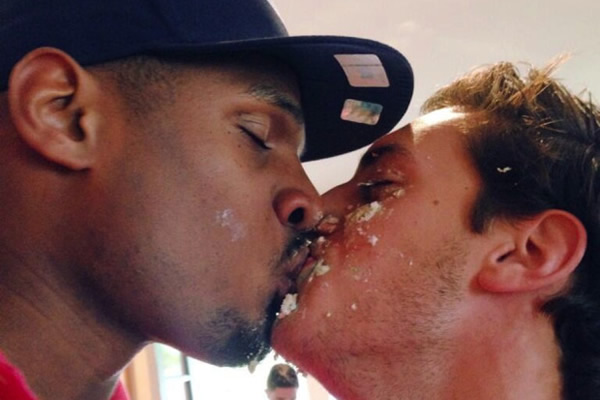

Michael Sam and Vito Commisano (Photo courtesy Cammisano’s pubic Twitter feed)

Michael Sam, Robin Roberts, Jason Collins, Tracy Chapman, Wanda Sykes, Don Lemon, Derrick Gordon are all high-profile gay African-American public figures and they all have white partners.

When Michael Sam shattered the glass ceiling and became the first openly gay man to get drafted in the NFL I was thrilled for him and full of pride as a gay black man. I noticed immediately though, when Michael Sam got the call from the coach of the St. Louis Rams he was in a sea of whiteness. He was the only African American in the room when he got drafted.

Would Michael Sam be celebrated as a hero to the LGBT community if he had a black boyfriend? A part of me was indeed happy that Michael Sam broke a barrier. When Michael Sam kissed his white twink boyfriend Vito Cammisano, I cringed. It took me a while to reflect on why I felt so disappointed in seeing Sam kiss his white lover. I wasn’t disgusted, I am an openly gay man and I have seen gay men kiss each other for more than a decade. I can also see the love Sam and Cammisano have for each other. However, I can’t shake the feeling that Sam — like other black gay public figures who have come out — follow the white gay standard.

There is a paucity of black gay public figures who are out and since images are important in society, the few black gay celebrities are sending the wrong message.

For people who are outsiders to black gay culture there are sociological reasons why Robin Roberts, Michael Sam, Don Lemon, Jason Collins and Derrick Gordon have white partners and it isn’t just about falling in love with another person. In the private sphere of black culture, there is a lot of homophobia that can cause a lot of psychological and emotional damage to a black gay person. The homophobia in black culture can lead a black LGBT person to harbor feelings of resentment and anger at the black community as a whole. Some black gays have a predilection to distance themselves entirely from black people in order to recover from the homophobia in the private sphere of black society.

For instance, Sam grew up in a broken home — his father deserted his family and his mother was a stereotypical pious black woman. My theory is that due to the homophobia in black culture, some black gay people just want to be accepted and I can understand that. Some black gays believe to assimilate into the white gay mainstream they can obtain social acceptance.

Everyone wants to belong, to be accepted for who you are and loved. This is the reason there is a clear pattern that when black gay public figures come out they have a predilection for white partners.

There is also a divide between black gays who are out of the closet and the black gays still closeted. Some black gays who are out and proud have a superiority complex. These out gay blacks believe they are better than blacks who are closeted because they have immersed themselves into the white gay world. Also, some black gays who are out make a conscious effect to obtain a white partner who is a symbol of moving up the social ladder.

But what deleterious subliminal messages are these black gay public figures sending to the black community?

I believe these out black gay public figures are sending mixed messages to the black community. Does a black gay person have to be with a white person in order to obtain social acceptance?

In the gay community, the standard of beauty is usually a young white male, under 40, in great shape and he is middle/upper class. This white gay male image is engendered in television shows such as HBO’s “Looking” and in gay magazines. There is also a lie that there are not out and proud black gay people. For instance, Atlanta is the gay black Mecca, despite being in the American South. It has a vibrant black gay community. D.C., Los Angeles, Chicago and New York City also have black queer communities with people out and proud. The dilemma is that although these black gay public figures are out since they tend to have white lovers there is a disconnect with black culture when they come out. When black people see high-profile public figures with white partners many blacks — gay or straight — are apathetic to them. These black gay public figures with white partners are just following the standard quo.

There simply isn’t the same political or social power seeing interracial gay public figures as couples than to see black gay or lesbian public figures as couples out and proud. It also is not empowering to see these interracial gay couples who are public figures because it is so one sided. Notice, you do not see a plethora of high-profile white gay public figures with black partners. People have a right to love whomever they desire. However, it would be foolish to ignore a clear pattern where black gay public figures come out yet are hypocritical. These black gay public figures tell society they are proud to be black and gay yet having a black gay partner by their side they are apathetic to it.

Orville Lloyd Douglas is author of the new book ‘Under My Skin’ published by Guernica Editions and available on Amazon.

Opinions

2026 elections will bring major changes to D.C. government

Mayor’s office, multiple Council seats up for grabs

Next year will be a banner year for elections in D.C. The mayor announced she will not run. Two Council members, Anita Bonds, At-large, and Brianne Nadeau, Ward 1, have announced they will not run. Waiting for Del. Norton to do the same, but even if she doesn’t, there will be a real race for that office.

So far, Robert White, Council member at-large, and Brooke Pinto, Council member Ward 2, are among a host of others, who have announced. If one of these Council members should win, there would be a special election for their seat. If Kenyon McDuffie, Council member at-large, announces for mayor as a Democrat, which he is expected to do, he will have to resign his seat on the Council as he fills one of the non-Democratic seats there. Janeese George, Ward 4 Council member, announced she is running for mayor. Should she win, there would be a special election for her seat. Another special election could happen if Trayon White, Ward 8, is convicted of his alleged crimes, when he is brought to trial in January. Both the Council chair, and attorney general, have announced they are seeking reelection, along with a host of other offices that will be on the ballot.

Many of the races could look like the one in Ward 1 where at least six people have already announced. They include three members of the LGBTQ community. It seems the current leader in that race is Jackie Reyes Yanes, a Latina activist, not a member of the LGBTQ community, who worked for Mayor Fenty as head of the Latino Affairs Office, and for Mayor Bowser as head of the Office of Community Affairs. About eight, including the two Council members, have already announced they are running for the delegate seat.

I am often asked by candidates for an endorsement. The reason being my years as a community, LGBTQ, and Democratic, activist; and my ability to endorse in my column in the Washington Blade. The only candidate I endorsed so far is Phil Mendelson, for Council chair. While he and I don’t always agree on everything, he’s a staunch supporter of the LGBTQ community, a rational person, and we need someone with a steady hand if there really are six new Council members, out of the 13.

When candidates call, they realize I am a policy wonk. My unsolicited advice to all candidates is: Do more than talk in generalities, be specific and honest as to what you think you can do, if elected. Candidates running for a legislative office, should talk about what bills they will support, and then what new ones they will introduce. What are the first three things you will focus on for your constituents, if elected. If you are running against an incumbent, what do you think you can do differently than the person you hope to replace? For any new policies and programs you propose, if there is a cost, let constituents know how you intend to pay for them. Take the time to learn the city budget, and how money is currently being spent. The more information you have at your fingertips, the smarter you sound, and voters respect that, at least many do. If you are running for mayor, you need to develop a full platform, covering all the issues the city will face, something I have helped a number of previous mayors do. The next mayor will continue to have to deal with the felon in the White House. He/she/they will have to ensure he doesn’t try to eliminate home rule. The next mayor will have to understand how to walk a similar tightrope Mayor Bowser has balanced so effectively.

Currently, the District provides lots of public money to candidates. If you decide to take it, know the details. The city makes it too easy to get. But while it is available, take advantage of it. One new variable in this election is the implementation of rank-choice voting. It will impact how you campaign. If you attack another candidate, you may not be the second, or even third, choice, of their strongest supporters.

Each candidate needs a website. Aside from asking for donations and volunteers, it should have a robust issues section, biography, endorsements, and news. One example I share with candidates is my friend Zach Wahls’s website. He is running for United States Senate from Iowa. It is a comprehensive site, easy to navigate, with concise language, and great pictures. One thing to remember is that D.C. is overwhelmingly Democratic. Chances are the winner of the Democratic primary will win the general election.

Potential candidates should read the DCBOE calendar. Petitions will be available at the Board of Elections on Jan. 23, with the primary on June 16th, and general election on Nov. 3. So, ready, set, go!

Peter Rosenstein is a longtime LGBTQ rights and Democratic Party activist.

Opinions

Lighting candles in a time of exhaustion

Gunmen killed 15 people at Sydney Hanukkah celebration

In the wake of the shooting at Bondi Beach that targeted Jews, many of us are sitting with a familiar feeling: exhaustion. Not shock or surprise, but the deep weariness that comes from knowing this violence continues. It is yet another reminder that antisemitism remains persistent.

Bondi Beach is far from Washington, D.C., but antisemitism does not respect geography. When Jews are attacked anywhere, Jews everywhere feel it. We check on family and friends, absorb the headlines, and brace ourselves for the quiet, numbing normalization that has followed acts of mass violence.

Many of us live at an intersection where threats can come from multiple directions. As a community, we have embraced the concept of intersectional identity, and yet in queer spaces, many LGBTQ+ Jews are being implicitly or explicitly asked to play down our Jewishness. Jews hesitate before wearing a Magen David or a kippah. Some of us have learned to compartmentalize our identities, deciding which part of ourselves feels safest to lead with. Are we welcome as queer people only if we mute our Jewishness? Are those around us able to acknowledge that our fear is not abstract, but rooted in a lived reality, one in which our friends and family are directly affected by the rise in antisemitic violence, globally and here at home?

As a result of these experiences, many LGBTQ+ Jews feel a growing fatigue. We are told, implicitly or explicitly, that our fear is inconvenient; that Jewish trauma must be contextualized, minimized, or deferred in favor of other injustices. Certainly, the world is full of horror. And yet, we long for a world in which all lives are cherished and safe, where solidarity is not conditional on political purity or on which parts of ourselves are deemed acceptable to love.

We are now in the season of Chanuka. The story of this holiday is not one of darkness vanishing overnight. It is the story of a fragile light that should not have lasted. Chanuka teaches us that hope does not require certainty; it requires persistence and the courage to kindle a flame even when the darkness feels overwhelming.

For LGBTQ+ Jews, this lesson resonates deeply. We have survived by refusing to disappear across multiple dimensions of our identities. We have built communities, created rituals, and embraced chosen families that affirm the fullness of who we are.

To our LGBTQ+ siblings who are not Jewish: this is a moment to listen, to stand with us, and to make space for our grief. Solidarity means showing up not only when it is easy or popular, but especially when it is uncomfortable.

To our fellow Jews: your exhaustion is valid. Your fear is understandable, and so is your hope. Every candle lit this Chanuka is an act of resilience. Every refusal to hide, every moment of joy, is a declaration that hatred will not have the final word.

Light does not deny darkness. It confronts it.

As we light our candles this Chanuka season, may we protect one another and bring light to one another, even as the world too often responds to difference with violence and hate.

Joshua Maxey is the executive director of Bet Mishpachah, D.C.’s LGBTQ synagogue.

Opinions

Holidays not always bright for transgender people

‘Home’ often doesn’t feel like home for trans folks

Christmas is family time, isn’t it? It seems like every TV ad, every rom-com with a Christmas tree and fairy lights, every festive novel in your local bookshop is trying to persuade you of this. To push it on you — and what’s wrong with it, you may ask? Well, just think about the thousands of people who cannot spend this holiday season with their loved ones. Think about the transgender community specifically.

Even without the increasingly hostile political climate against trans people in modern-day America, many of them are not welcome in their own families. It is not something that started with MAGA, although MAGA certainly made it worse. “Home Alone” is not a comedy when your family does not accept you, and you are stuck all alone on Christmas. I’ve never been alone at holidays, but I know — as a trans person who has always loved family stories but estranged from their family — how the season can be tough.

Let’s make it clear: I like the holiday season, and I would never ask you to cancel it. I just want you to support your trans friends, and the trans community in general.

According to recent data from the Williams Institute at UCLA, more than 2.8 million people in the U.S. now identify as trans, including roughly 724,000 youth aged 13–17. And not all of them are out or accepted at home. That means many thousands are navigating teenage years — the years when so many family traditions, holidays, and emotional expectations are formed — while being invisible to their own families, or abused by them.

But for a large proportion of trans people, “home” doesn’t feel like home.

In the landmark 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, many of respondents who were out to their immediate family reported some form of rejection: relationships ending, being kicked out, being denied the ability to express their gender, or being sent away.

Among those who did experience family rejection, 45 percent had experienced homelessness.

Other research shows how deeply rejection affects health: trans youth without family support face far higher rates of psychological distress, suicidality, and substance misuse.

So when you hear “Christmas is family time,” for many trans adults that message comes with flashbacks and pain. For trans kids it may be worse.

Also, intersectionality made everything even hard. Take trans people of color. A report on Black trans Americans found:

- 42 percent had experienced homelessness

- 38 percent lived in poverty

- Rates of sexual violence, mistrust of authorities, and fear of asking for help were also significantly higher

And if a trans person is also disabled, autistic, or living with chronic health conditions, the barriers become even bigger. Just imagine what it is like when your parents try to change you for being autistic all your childhood, and then kick you up for being trans. Ableism often goes hand in hand with transphobia; support systems become less accessible; and acceptance becomes harder to find. Holidays meant not just that you sometimes couldn’t share fun because of lack of inclusion now, but also because of mental health issues triggered by the past.

So yes — when you talk about Christmas stories of family, warmth, fairy lights and acceptance, it’s important to remember that for many trans people, Christmas is not something nice and cozy. Many trans people are suffering from PTSD, and for people with PTSD holidays are often a trigger.

So what can you do, as a trans ally or another trans person who wants to help their trans siblings? What does a “trans-friendly Christmas” look like for those estranged from their families?

Supporting a trans person at Christmas doesn’t have to be perfect. It doesn’t demand huge gestures, it doesn’t mean that you should stop celebrating or play Grinch. Just remember that not everyone is celebrating. And even people like me, who are celebrating, sometimes feel too triggered by all the perfect family pictures.

But there is some way to help your trans friends.

Give them space. Not everyone wants to talk about Christmas. Not everyone wants to explain their estrangement. They may withdraw, or avoid festive events entirely. Respect that. As an expert working with mental health services, I can say that sometimes the best gift is the room to breathe.

Say: “I know this time of year can be difficult. I’m here if you want to speak, and I’m here if you don’t.” Or share your own bad experience, especially if you are speaking with autistic person.

Or just ready to support them in a way they need.

Acknowledge the pain, without feeling guilty if it’s not your fault, and provide some support.

This might mean:

- Inviting them to your home for a meal

- Checking in with a simple, trans-friendly message (“thinking of you today — hope you’re doing whatever feels right for you”) — especially if they like this kind of messages

- Suggesting a walk, a film night, or anything that doesn’t revolve around “family”

- Bringing them into chosen family traditions if they’re open to it

- Support trans community online

- Just share photos of your pets

Be prepared for triggers. Really. I often have a relapse in my mental health on holidays despite liking them. Or, because I have Dissociative Identity Disorder, I struggle with my child’s personality. Your friends who have PTSD or DID can have similar problems. Respect them even if they behave “childishly” — even when a person is mentally falling into their child state, remember that they still have agency. Listen to their stories. Help them create their own holiday traditions if they need to, or ask for professional help. Be patient. Depression, anxiety, or OCD can also be triggered during holidays even if a person with those conditions is in remission.

And, most important of all: listen.

Some trans people want community on Christmas. Some want silence. Some want to escape. Some want a tiny piece of normality. Some want their own queer or geeky Christmas. Some prefer to celebrate the new year. There is no universal script. Let them decide. And remember: support is the most important thing.

Not the holiday decorations. Not the perfectly curated “inclusive holiday.” Not expensive parties.

Because for many trans people who have lost their family, especially at Christmas, it is important to know that someone sees them, someone calls them by their chosen name, someone cares, someone wants them here even if their parents don’t.

And sometimes, that’s enough to make the season not just survivable, but enjoyable. This, by the way, is true for all holidays, whether it’s Hanukkah or New Year’s Eve.