Books

The friendship between a first lady and a ‘Firebrand’

Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt bonded during civil rights movement

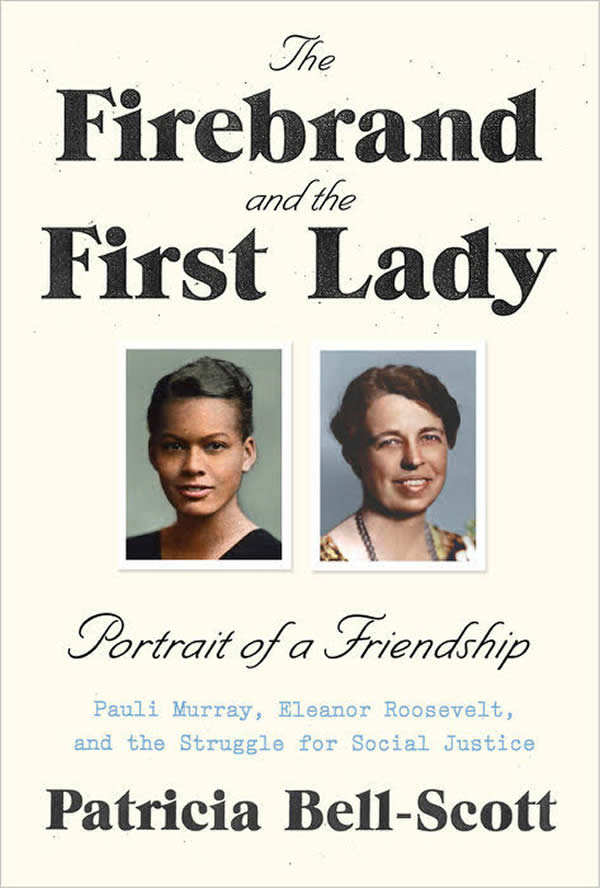

Patricia Bell-Scott explores the friendship between Eleanor Roosevelt and Pauli Murray in her new book.

Most of us would be proud to have earned a degree, written an acclaimed book of poetry or memoir, worked tirelessly for civil rights and have been part of a friendship that fostered human rights.

Pauli Murray, the groundbreaking African-American activist, lawyer, writer and priest, who lived from 1910-1985 and was attracted to women, did all this and much more. For nearly 25 years, Murray the granddaughter of a mixed-race slave, was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt, whose privileged background entitled her to belong to the Daughters of the American Revolution. (Roosevelt resigned from the DAR in 1939 when the group prohibited the renowned African-American singer Marian Anderson from performing at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C.)

In her compelling new book “The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice,” Patricia Bell-Scott, editor of the anthology “All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave,” tells the story of this extraordinary relationship. Bell-Scott is professor emerita of women’s studies and human development and family science at the University of Georgia. Her previous books include: “Life Notes: Personal Writings by Contemporary Black Women” and “Double Stitch: Black Women Write about Mothers and Daughters,” which won the Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book Prize.

From 1938-1962, their friendship was sustained by some 300 postcards and letters as well as personal visits. The relationship began when Murray, 27, working for the WPA, a New Deal agency, sent Eleanor Roosevelt a letter protesting a speech Franklin Delano Roosevelt had made at the University of North Carolina. (The university had refused to admit Murray as a student because she was black.) The friendship continued until Roosevelt, 26 years older than Murray, died in 1962.

Murray earned three law degrees, organized sit-ins in the 1940s while a student at Howard University against eateries that discriminated against people of color, participated in bus boycotts 15 years before Rosa Parks and created the legal strategy that ensured that sex discrimination was included in the Civil Rights Act.

A co-founder of the National Organization for Women, Murray wrote the memoir “Proud Shoes,” the well-regarded poetry collection “Dark Testament” as well as numerous essays and books. In 1977, she became one of the first women to be ordained as a priest by the Episcopal Church. Though Murray hadn’t been involved in writing it, in 1971 Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in an homage to Murray’s work, listed her as a co-author in her first brief before the Supreme Court.

Born in Baltimore, Murray didn’t use her given name “Anna Pauline.” Her father was a teacher and her mother was a nurse. At age three, after her mother died, Murray went to Durham, N.C., where she lived with her grandparents and two of her aunts, one of whom became her adoptive mother. In her childhood, Murray’s father, after contracting what was thought to be encephalitis, suffered from “unpredictable attacks of depression and violent moods.” Murray wasn’t ashamed of her sexual orientation and was in a long-term relationship with Irene, “Renee” Barlow. Yet, because of homophobia and her race, she was often denied employment in the government and the private sector.

It’s no wonder that it took Bell-Scott 20 years to write “Firebrand.” Recently, she talked with the Blade about the book and the friendship between Murray and the woman, who Murray called “Mrs. R.”

“This was not something I intended to do,” Bell-Scott said of “Firebrand.” “I was working on another project at the time.”

Then in 1983, Bell-Scott asked Murray to serve as a consulting editor to “SAGE: A Scholarly Journal of Black Women,” of which she was a co-founding editor. Though Murray couldn’t do SAGE, she wrote a letter of “encouragement” to Bell-Scott. “Pauli wanted to work on her autobiography,” she said.

In a follow-up to this letter, Murray wrote to Bell-Scott, “You need to know some of the veterans of the battle whose shoulders you now stand on.”

She didn’t say, “know me better,” Bell-Scott said, “but she did say she took great pride in her work as a member of the subcommittee on legal rights of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women. (President John F. Kennedy appointed Eleanor Roosevelt chair of the commission.)

Bell-Scott made notes of what she wanted to talk about with Murray when her writing project was finished. “But I didn’t get the chance —18 months later, she died of pancreatic cancer,” she said. “Her letter haunted me. Quite a few years later, I decided I was still so haunted by her comment about knowing the veterans on whose shoulders you’re standing on.”

After examining the collection of Murray’s letters at the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University and the collection of Roosevelt’s letters at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Bell-Scott said, she “immediately recognized that their relationship deserved attention.” Their friendship is mentioned only briefly by historians and biographers.

Despite the fact that Murray and Roosevelt came from very different backgrounds, they had a lot in common, Bell-Scott said. “To begin with, Anna was the given name for both of them and they never used it,” she said. “They both lost their parents before their teens and were sent to live with elderly kin.”

They were sensitive kids who grew up to be compassionate women with a thirst for justice, Bell-Scott said. “Even though she was first lady, people made fun of Eleanor’s appearance and ridiculed her teeth,” she added. “Pauli was boyish looking. People poked fun at how she looked.”

Murray and Roosevelt loved their fathers who suffered from mood disorders and alcoholism respectively. Though they were outspoken and highly energetic in their quest for social justice, “people were often surprised to learn that Pauli and Eleanor were both shy,” Bell-Scott said. “It took them tremendous psychic energy to overcome their shyness.”

Both were voracious readers and avid writers. Though she was a committed social justice activist, lawyer and priest, writing was what was closest to Murray’s heart, Bell-Scott said. “Pauli couldn’t turn away from activism,” she said, “but if there were any regrets – she would have liked to have written more.”

Roosevelt, too, was committed to her writing, Bell-Scott said. “Eleanor wrote her ‘My Day’ column even when she was first lady,” she said. “After FDR’s death, she reported on Russia and pursued other writing projects.”

Their sense of well being was dependent on having meaningful work and exercise, Bell-Scott said. “They had a talent for friendship. And they loved dogs. Eleanor liked Scotties and Pauli liked mutts and strays.”

Murray would work herself into exhaustion and crash, Bell-Scott said. “She suffered from mood swings which weren’t properly diagnosed as a thyroid disorder until Pauli was in her 40s,” she said. “Eleanor suffered episodes of depression.”

Their friendship was the context that allowed Murray and Roosevelt to grow into the “transformative leaders that we know them as,” Bell-Scott said. “When they first met, Pauli was an impatient young radical … Eleanor felt it was important to always consider taking social justice action with great caution – to always follow the muted action on civil rights of the Roosevelt administration.” (FDR never publicly pushed Congress to speak out against lynching, Bell-Scott said.)

Later in their lives, Bell-Scott said, Murray had moved from radical left to left of center – voting for Lyndon Johnson as a registered Democrat after decades of voting for Socialist candidates. By the 1960s, Roosevelt had put her life on the line at civil rights workshops and demonstrations.

“When I look at the issue of Pauli’s sexuality, I think of the social context of the time. Here is a woman coming to adulthood in the 1920s, 30s and 40s,” she said. “Homosexuality is defined as a mental disorder until the 1970s. Pauli, a very bright woman, reads the scientific literature.”

Added to this, Bell-Scott said, was the homophobia of McCarthyism, which considered LGBT people to be a security threat. “Pauli was a black woman lawyer,” she said, “ that’s an unconventional career for a woman. There are rumors about her sexuality and her mental health. She is living with discrimination on so many fronts.”

But Murray wasn’t ashamed of who she was, Bell-Scott said. “She was raised as a child by elder kin with Victorian values. You didn’t talk about sexuality.”

From reading Murray’s letters and sermons from later in her life, “it seems to me that Pauli began to publicly embrace herself,” Bell-Scott said.

Books

‘Pronoun Trouble’ reminds us that punctuation matters

‘They’ has been a shape-shifter for more than 700 years

‘Pronoun Trouble’

By John McWhorter

c.2025, Avery

$28/240 pages

Punctuation matters.

It’s tempting to skip a period at the end of a sentence Tempting to overuse exclamation points!!! very tempting to MeSs with capital letters. Dont use apostrophes. Ask a question and ignore the proper punctuation commas or question marks because seriously who cares. So guess what? Someone does, punctuation really matters, and as you’ll see in “Pronoun Trouble” by John McWhorter, so do other parts of our language.

Conversation is an odd thing. It’s spontaneous, it ebbs and flows, and it’s often inferred. Take, for instance, if you talk about him. Chances are, everyone in the conversation knows who him is. Or he. That guy there.

That’s the handy part about pronouns. Says McWhorter, pronouns “function as shorthand” for whomever we’re discussing or referring to. They’re “part of our hardwiring,” they’re found in all languages, and they’ve been around for centuries.

And, yes, pronouns are fluid.

For example, there’s the first-person pronoun, I as in me and there we go again. The singular I solely affects what comes afterward. You say “he-she IS,” and “they-you ARE” but I am. From “Black English,” I has also morphed into the perfectly acceptable Ima, shorthand for “I am going to.” Mind blown.

If you love Shakespeare, you may’ve noticed that he uses both thou and you in his plays. The former was once left to commoners and lower classes, while the latter was for people of high status or less formal situations. From you, we get y’all, yeet, ya, you-uns, and yinz. We also get “you guys,” which may have nothing to do with guys.

We and us are warmer in tone because of the inclusion implied. She is often casually used to imply cars, boats, and – warmly or not – gay men, in certain settings. It “lacks personhood,” and to use it in reference to a human is “barbarity.”

And yes, though it can sometimes be confusing to modern speakers, the singular word “they” has been a “shape-shifter” for more than 700 years.

Your high school English teacher would be proud of you, if you pick up “Pronoun Trouble.” Sadly, though, you might need her again to make sense of big parts of this book: What you’ll find here is a delightful romp through language, but it’s also very erudite.

Author John McWhorter invites readers along to conjugate verbs, and doing so will take you back to ancient literature, on a fascinating journey that’s perfect for word nerds and anyone who loves language. You’ll likely find a bit of controversy here or there on various entries, but you’ll also find humor and pop culture, an explanation for why zie never took off, and assurance that the whole flap over strictly-gendered pronouns is nothing but overblown protestation. Readers who have opinions will like that.

Still, if you just want the pronoun you want, a little between-the-lines looking is necessary here, so beware. “Pronoun Trouble” is perfect for linguists, writers, and those who love to play with words but for most readers, it’s a different kind of book, period.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

‘The Cost of Fear’

By Meg Stone

c.2025, Beacon Press

$26.95/232 pages

The footsteps fell behind you, keeping pace.

They were loud as an airplane, a few decibels below the beat of your heart. Yes, someone was following you, and you shouldn’t have let it happen. You’re no dummy. You’re no wimp. Read the new book, “The Cost of Fear” by Meg Stone, and you’re no statistic. Ask around.

Query young women, older women, grandmothers, and teenagers. Ask gay men, lesbians, and trans individuals, and chances are that every one of them has a story of being scared of another person in a public place. Scared – or worse.

Says author Meg Stone, nearly half of the women in a recent survey reported having “experienced… unwanted sexual contact” of some sort. Almost a quarter of the men surveyed said the same. Nearly 30 percent of men in another survey admitted to having “perpetrated some form of sexual assault.”

We focus on these statistics, says Stone, but we advise ineffectual safety measures.

“Victim blame is rampant,” she says, and women and LGBTQ individuals are taught avoidance methods that may not work. If someone’s in the “early stages of their careers,” perpetrators may still hold all the cards through threats and career blackmail. Stone cites cases in which someone who was assaulted reported the crime, but police dropped the ball. Old tropes still exist and repeating or relying on them may be downright dangerous.

As a result of such ineffectiveness, fear keeps frightened individuals from normal activities, leaving the house, shopping, going out with friends for an evening.

So how can you stay safe?

Says Stone, learn how to fight back by using your whole body, not just your hands. Be willing to record what’s happening. Don’t abandon your activism, she says; in fact, join a group that helps give people tools to protect themselves. Learn the right way to stand up for someone who’s uncomfortable or endangered. Remember that you can’t be blamed for another person’s bad behavior, and it shouldn’t mean you can’t react.

If you pick up “The Cost of Fear,” hoping to learn ways to protect yourself, there are two things to keep in mind.

First, though most of this book is written for women, it doesn’t take much of a leap to see how its advice could translate to any other world. Author Stone, in fact, includes people of all ages, genders, and all races in her case studies and lessons, and she clearly explains a bit of what she teaches in her classes. That width is helpful, and welcome.

Secondly, she asks readers to do something potentially controversial: she requests changes in sentencing laws for certain former and rehabilitated abusers, particularly for offenders who were teens when sentenced. Stone lays out her reasoning and begs for understanding; still, some readers may be resistant and some may be triggered.

Keep that in mind, and “The Cost of Fear” is a great book for a young adult or anyone who needs to increase alertness, adopt careful practices, and stay safe. Take steps to have it soon.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Hurt Capital’ chronicles young life of bipolar, trans writer

New book from Isaac Amend a rich and complicated tale

Washington Blade contributor Isaac Amend has published a new book, “Hurt Capital,” chronicling a range of topics related to his transgender status, a personal struggle following a psychotic breakdown, and more.

BLADE: Why did you write this book and why now?

ISAAC AMEND: In college, I was an avid writer for the Yale Daily News, and tried to prepare myself for a good writing career, taking classes with Pulitzer Prize-winner Michael Cunningham, and other notable authors, including Anne Fadiman and Cynthia Zarin. But when I got out of college, I spent six or seven years in the real world, outside of Ivy gates, racking up experiences to write about — whether it was falling in love with a woman, getting hit by a car in Cyprus, or being manic for 13 months straight. But once all of those things were done, I went back to my literary roots, frantically scribbling books and articles in my room at night. Now I want to have some sort of writing career, and I can partly thank the Blade for that, as you welcome most of my op-eds.

I felt like it was important to write about bipolar disorder in very honest and raw terms. I experienced a psychotic break from reality when I was 19 years old that I felt ashamed to tell everyone in my life about, but now I want to come clean with it. Recovering from a psychotic break is a complicated process, and I’ll never really know if my mind has fully recovered, but I do know that because of my break from reality, I’m able to tackle difficult problems in life without getting scared. I feel like it’s also important for the general public to know about how much hurt and pain transgender people feel on a daily basis, hence the name “Hurt Capital.”

BLADE: Who’s the audience for your book?

AMEND: It’s funny, this is a question that all authors need to answer in a book proposal to agents, and I did exactly that, querying dozens of agents. My book has three target audiences. The first are expats, or expatriates. These are people who live overseas — either on embassies in South Asia or in suburban compounds on the outskirts of Moscow. These are the places that I grew up in, and I felt “genderless” for some of my time as an expatriate, frolicking to and fro with not a worry in the world as I grew up in Pakistan and India. I want to connect with other people who have lived overseas.

The second target audience for my book are twins. I have an identical twin named Helen who is my best friend. I’m constantly trying to be a good brother to her, whether it’s helping her move apartments or buying her groceries. We connect on a very deep level, and I’m sure that my gender transition partly shocked her and in some ways, may have made her feel upset. It’s a unique phenomenon when one identical twin wants to be a man, and the other one wants to stay a woman. I’ll never fully understand how God made me bipolar and trans while he made my twin sister non-bipolar and cisgender.

The third target audience for my book are individuals with mental health issues. I want to connect with other people who have also gone through psychotic breaks, been manic, talked at the speed of light, felt depressed, or felt so anxious that they had to pop a lot of pills and stay in bed. I want to connect with people who suffer from schizophrenia, bipolar, ADHD, and OCD, among many other diseases. These disorders are so complicated in nature, but we need to be honest about their dimensions and how to best treat them.

BLADE: How long did it take to write and what was your process?

AMEND: The book didn’t take me long to write. I churned out around 5,000 to 7,000 words in one week, then I had a 500 word per day policy — it’s a policy I implement with all of my books. I would write 500 words per day usually at a bar at night. I was living in D.C. back then and would frequent Nanny O’Brien’s, a well-known Irish dive bar open late. I would pull out my iPhone and write 500 words (but usually more) in Google Docs. There were all sorts of characters at Nanny O’Brien’s — bartenders who would scream at me if I didn’t tip enough, people from the Russian embassy, and famous politicos who would bring their golden retriever in tow. I almost got into a fistfight there with a Russian diplomat, but still miss the memories that bar curated. I even told my landlord at the time that I associated Nanny O’Brien’s with the book.

BLADE: What are you thoughts on how the new Trump administration has attacked trans rights and do you see any hope in the near future?

AMEND: It’s a travesty, what’s going on. The new administration is cruel beyond belief, yet I still retain some semblance of hope for the future. I see our nation as divided, but a nation that still elects an almost equal amount of Republicans to the presidency as it does Democrats. Most large cities in the U.S. are dominated by progressive people who understand the value in diversifying sexuality and gender identities, and celebrating that diversity. I always tell people to “vote with their feet,” as in, if you have the privilege of being able to move to a new location, move to a city that is full of liberal minded people. But many trans youth don’t have the privilege of moving; they are stuck in schools full of students that bully them for their gender. Indeed, there is a massive mental health crisis happening among trans youth. The Trump administration has banned everyone under the age of 19 from receiving gender affirming care, and that is cruel. I have spoken openly about my belief that adolescents and other youth should be able to access puberty blockers, and I maintain that stance.

This seems out of left field, but I’ve seriously thought about pooling money together to pay for trans youth to receive medical care in Canada. It’s sort of a gauche idea, because trans youth presumably need to stay in school in the U.S., and their parents would have to agree to them going up north, but the idea still persists in my head. I guess I dream of ways that these kids can feel better, and receiving care in Canada comes to mind.

BLADE: What’s your message to young trans kids who are frightened during these difficult times?

AMEND: Keep your head up. Older trans people like me are fighting for you to have better lives. If someone tries to put you down in school just remember that they are putting you down out of an insecurity they harbor about themself or the world. Secretly, they feel inferior. Don’t forget that the qualities that you bring to the table — your unique gender and/or sexual identity — is what makes you beautiful.

BLADE: There are many queer memoirs out there; what’s unique about your story?

AMEND: My story is intersectional, meaning I weave a story about a transgender man who is also bipolar and is a twin and grew up overseas in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, India, Russia, and Jordan. It’s not a one-dimensional story. It’s rich and complicated with tales of being manic and going on testosterone and being psychotic and hoping that I don’t lose all of my marbles in front of my twin and little sister and the rest of my family. I speak of KGB henchmen in Russia and spooks here in D.C. (kind of like that Russian diplomat who almost tried to punch me). I speak of many things—not just being queer.

The following is an excerpt from “Hurt Capital,” which is available now at Amazon and other retailers.

Dear Mom,

The pills in my bathroom cabinet are sitting next to each other like fifteen linebackers on a football field. Bolton. Edmunds. Greenlaw. Wagner. Warner. The Chiefs are winning, and I haven’t even spotted Travis Kelce yet. They’re all famous–each single pill bottle–each capsule I need to swallow with orange juice at night. I get the high pulp kind, now, from Trader Joe’s, that costs around four bucks. Semi pulp doesn’t put the tablets down fast enough. I’ve got every kind of med imaginable since my first episode ten years ago.

Bipolar has never felt so bad. But it’s also never felt so good. The mania that lasted for a year last September has crept away, but its high still remains in my head. At least partly. Partially. Essentially. Basically, it was awesome. I celebrated at every turn. Went walking for hours on end, only to feel my breath creeping into my lungs, and out, past midnight, when I dreamt of fairytales and candy cane land and piles of dollars stacked so high in front of Rick Ross. So high that he forgot he sold coke. I forgot he sold coke. I forgot a lot of that year, Mom.

Iwant to be like Rick Ross one day. I want to star in a song with Drake. Rapping about lemon pepper chicken and taking my celebrity son to French Montessori. I want to be a hustler, a gangster at every turn, a coke warlord just fiending for a kingdom. The kingdom I create is in my mind: it’s ruled by Dostoevsky and Tolstoy and even Pushkin. I named a cat after Pushkin. Russian writers have never felt so real. I want them to come back from the dead and resurrect themselves–all polished and everything. No wax. I remember visiting Tolstoy’s grave with you in Moscow, when henchmen roamed the city at night and CIA officers were prowling the embassy’s corridors. I was scared in Moscow. Scared back then. Scared of my female body. But now it’s a male one, and I’m a son. I’m your son, Mom. But I’m troubled. Very troubled indeed.

I went to a soccer game again. We are named Footyholics. We played near Logan Circle, in the backyard of a school, and I swear the soccer ball was going to kill me. It hit my head, with a bang–not a whimper–and zoomed past some crust on my earlobes. My black stud almost shook for a bit. I clenched the ring you got me on my index finger. You got it from Delhi, and now I’m remembering things back there as well, when you and I lived in India. But there are many things I still can’t remember, Mom. Just trust me on that one. Trust me.

Here’s one thing I do remember, though: getting in that car accident with you. In Delhi. You were all up in the front seat, and Helen and I were in the back. And a motorcyclist went clamp on the right window, and his flesh and blood were splayed all near for us to see. He died that day, and I think that’s the first time I ever saw you cry. I only saw you cry a second time, when Dad was in Kabul, and you missed him like hell, and Phoebe had a tantrum on the National Gallery steps, and you drove us back home, teary-eyed, and you just sat crying that day, in the DC suburbs. And there was not a damn thing I could do about it.

We lost the soccer game. Footyholics lost. But we grabbed a few beers after, at a place near the traffic circle, where expats and missionaries and bankers were fiending for a beer as well, all alike, just as I was fielding for a kingdom in my head. I swear this city is ruled by sociopaths sometimes. They just crawl around here, like ants around a hill, waiting to wreak havoc.

At the bar we were sitting outside, on a wooden table, and we all ordered some beers and some tacos and stuff. And some burritos with chicken. And I swear I shouldn’t drink, but I’m just like your husband–there’s nothing that tastes better than alcohol in this world, Mom. But beer is bad for me. It’s bad for a guy who thinks a soccer ball is going to kill him. At the restaurant, I spotted a street sweeper brushing away leaves. I suddenly fixated on the sweeper: on his crew cut, his black boots, his leather skin. I thought he was manic for leaves. I also thought the waitress hated Jesus until a cross kissed her neck. I thought many things, Mom, and none of them were true.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

El Salvador4 days ago

El Salvador4 days agoGay Venezuelan makeup artist remains in El Salvador mega prison

-

State Department3 days ago

State Department3 days agoHIV/AIDS activists protest at State Department, demand full PEPFAR funding restoration

-

Brazil3 days ago

Brazil3 days agoUS lists transgender Brazilian congresswoman’s gender as ‘male’ on visa

-

District of Columbia4 days ago

District of Columbia4 days agoTwo charged with assaulting, robbing gay man at D.C. CVS store