a&e features

Marsha P. Johnson and pal Sylvia Rivera key players in Stonewall legacy

Filmmaker, family, young trans people recall New York LGBT icons

Ten-year-old Xander came out as nonbinary-femme this year to their elementary school. Transgender service member Terece began transitioning to female while still a sailor on active duty. Both recognize their historical debt to Stonewall activist Marsha P. Johnson.

According to many sources and records, Johnson was an African-American self-identified drag queen and regular at New York’s Stonewall Inn, a mafia-owned gay bar catering to a crowd of mostly queer minorities, gender non-conformers and homeless youth.

On June 28, 1969, the bar was raided by police and many reported Johnson and others fought back, resulting in rioting and later a commemorative march that would evolve into modern Pride parades.

Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, a trans woman of color and her friend, would go on to found STAR, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, a charity and shelter for homeless transgender teens.

After decades of activism punctuated by poverty, homelessness and mental illness, Johnson died in 1992 under suspicious circumstances. Rivera would die 10 years later from liver cancer after a lifetime devoted to trans activism.

But it’s a history Millennial and Gen Z genderqueer youth like Terece and Xander have had to learn on their own.

“I have heard of Stonewall,” says Xander, who uses they/them pronouns. “I’m actually reading a book about the Stonewall riots … and I listen to a queer history podcast.”

“I know a little about the Stonewall uprising,” Terece says. “I’m learning on my own. I went to school in the ‘90s … so anything regarding LGBT rights has been self-study in my adult life now.”

Both are aware of its impact on their lives.

“I am aware of Marsha P. Johnson and her role in the Stonewall events,” Terece says. “To me Marsha is a trans woman of color who saw abuse and misjustice within her community and decided to take a stand. She is a figure of which we look to for guidance for how trans people should be treated.”

Xander is just starting to hear about people like Rivera and Johnson. Some previous wrongs are slowly being righted. Johnson’s likeness is front and center on a new YA book called “What Was Stonewall?” by Nico Medina. In 2018, Johnson received a lengthy obit in the New York Times in its “Overlooked” series that supplies obits of those initially overlooked at the times of their deaths.

Albert Michaels, Johnson’s nephew (who’s straight), says Johnson’s legacy and name recognition are sadly uneven.

“I’m finding … especially in her hometown of Elizabeth (N.J.), Marsha’s not really known there,” Michaels says. “Every time something goes on (to commemorate her) I post it to my Facebook page or post it to a community page. I mean, here, nobody really knows about Marsha, straight community, trans community or otherwise. Even when I did an interview the other day in front of Stonewall and I went inside for the first time into the bar, no one really knew about Marsha. There was one guy who knew … and yet they all had these T-shirts and were selling them for Pride. But there would be no Pride or no Stonewall if this whole event didn’t happen.”

Though he was just 8 in 1969, the weight of the loss adds emotion to his voice.

“It’s sad to me. I went there (to Stonewall Inn) for some kind of enlightenment … and I felt very disappointed. … I never saw Marsha in New York and to this day that is one thing that I regret. That I never went to search for Marsha, never walked the streets with Marsha … and to see things through Marsha’s eyes.”

David France, director and producer of the Netflix documentary “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson,” did meet Johnson in New York after moving there in 1981 and deeply appreciated the opportunity.

“The queer community was still a very small and geographically bounded community and all gay life centered on Christopher Street,” he says.

France’s voice lifts as he remembers a happier time as well as “Marsha’s joy.”

“Christopher Street had a number of prominent characters,” he says. “And the most prominent of them was always Marsha. If you got in with Marsha, you felt like you had found a home. She made you feel at home. I was introduced to her in 1981 and not that she and I were friends, but I can say she served as a kind of an ambassador’s role to newcomers as they arrived in the city. And especially to the young people that she took under her wing. And I felt that in a small way she had bestowed some of that attention on me and I especially looked up to and felt grateful for that.”

Michaels also appreciated Johnson’s motherly attention.

“I knew Marsha all my life as a kid,” Michaels says. “When my memories shift of Marsha, I go back to the ‘70s and that 8-year-old kid.”

His early memories of Johnson and the riots add color to the often white, middle-class narratives younger generations like Terece and Xander are reading.

“Marsha was quite blunt and quite frank with me,” Michaels says. “She would talk about harassment from police and people mistreating her and how people were evil to each other. Telling me be true to myself and don’t let anyone change me, and to get my education. Basically, the things that a mother or a father would tell their children, basic things in life to try to get you along.”

She once spoke of getting shot in the butt by a taxi driver. And of being beaten by cops and her “johns.”

“She was straight with me,” he says. “She said you gotta be aware. And that actually helped me. That helped me be who I am today.”

Although he was young and didn’t understand the significance of it at the time, Michaels remembers Johnson coming home shortly after Stonewall frustrated and angry.

“I think she said there was some kind of riot,” he says. “And that she was tired of ‘them pigs’ and they couldn’t take it anymore and they finally stood up for their rights.”

“Half of it went in and half of it went out, but I remember pieces of it,” he says.

France fills in some of the gaps with his own research and personal knowledge.

“Marsha and Sylvia were a partnership,” he says. “Marsha helped raise Sylvia … and they did everything together using different strategies.”

They built one of the first trans empowerment organizations called STAR and embraced the “people power movement” of the ‘60s and ‘70s,” he says. They envisioned it becoming the chief activist trans movement and tried to build community with other iconoclastic groups of the era such as the Black Panthers.

France says Johnson and Rivera helped start “today’s conversation” about gender nonconformity and civil rights.

“They were the first people who conceptualized the idea that the trans community was a distinct community,” he says. “With a deep sense of the unifying goals and needs … they organized specifically around that. I think this had not ever before been conceptualized in that way. In that way I think they were genuine revolutionaries.”

However, France describes a pervasive lack of acceptance even among gays, culminating in Rivera being ostracized from the movement. Some didn’t want “transvestites” seen as part of their efforts. Rivera jumped on the stage at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally (i.e. New York Pride) and argued for trans inclusion in the movement.

France says seeing so much racism, transphobia and trans murders, especially for trans women of color, inspired him to explore Johnson’s death. He was hired by the Village Voice to investigate her murder in 1992 but never solved it.

“I remembered Marsha and her gift and (her death) being a significant tragedy in the community from the early ‘90s. I remember it because I was up there and I knew Marsha,” he says.

“That was a terrible year,” he says, noting he lost a partner to AIDS about the same time. “And I always felt like I had let that story down and had let Marsha down as a result. And I felt that if I could tell her story with some power I could really find a way to bring attention to this new unaddressed epidemic of violence against the trans community … that was my goal when I started the film.”

Johnson’s nephew also felt her death personally. He says the criminal justice system failed her and others in similar situations.

“First thing I knew about her murder,” he says, “is basically from what the police report said. She was going to different community functions … and initially the police had her death down as a suicide. (Later) people were calling our house, trying to get in contact with us. They saw Marsha and (said she) didn’t appear suicidal. So, we were trying to get that report changed.”

Unfortunately, not much progress has been made in the investigation.

“As far as we know, it’s in some kind of limbo,” France says. “Does that mean it is still an active file? They will not report that to us … so, we don’t know if they advanced the investigation.”

Today, Michaels attends Black Trans Lives Matters events “to lend support” on behalf of his slain, pioneering aunt.

“I think Marsha’s legacy is important to all walks of life, no matter what your sexual orientation is and no matter what your gender expression is,” he says. “You always have the people who are trying to lead the way as examples. Marsha and Sylvia, what they started; this is not over. They lit the flame, but this is not over.”

France says modern trans organizations have their origins in Johnson and Rivera’s work.

“We would not be having this discussion today if it were not for them,” he says. “They gave us the framework for this discussion.”

Johnson’s nephew speaks of continuing her legacy.

“I keep in touch with Sylvia Rivera’s adopted daughter, Xenia. We were talking about even starting up another program like STAR, but I’ve never done anything like that before so I have to get in contact with the right people.”

Michaels remains hopeful.

“Xenia is an advocate and she’s been keeping me up to date on what’s been going on,” he says. “And we sort of said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if Sylvia and Marsha kind of rose again?’”

a&e features

Peppermint thrives in the spotlight

In exclusive interview, she talks Netflix show — and the need to resist Trump’s attacks

As an entertainer, there’s not much that Peppermint hasn’t done. She’s a singer, actor, songwriter, reality TV personality, drag queen, podcaster and the list goes on. Most importantly, as an activist she has been an invaluable role model for the trans, queer, and Black communities.

She’s a trailblazer who boasts an impressive list of ‘firsts.’ She is the first out trans contestant to be cast on “RuPaul’s Drag Race” (Season 9). She is the first trans woman to originate a principal musical role for Broadway’s “Head Over Heels.” She was also the first trans woman to compete in the runaway hit series “Traitors,” on Peacock, and she is the ACLU’s first-ever Artist Ambassador for Trans Justice. Her accolades are a true testament of the courage it took for Peppermint to live her authentic self.

We caught up with Peppermint to chat about her activism, taking on bigger roles on screen, our current political and social climate and life beyond the lens. For Peppermint, coming out as trans was not just a moment of strength—it was a necessity.

“It unfolded exactly as I had imagined it in terms of just feeling good and secure about who I am. I was in so much pain and sort of misery and anguish because I wasn’t able to live as free as I wanted to and that I knew that other people do when they just wake up. They get dressed, they walk out the door and they live their lives. Being able to live as your authentic self without fear of being persecuted by other people or by the government is essential to being healthy,” Peppermint tells the Blade in an exclusive interview.

“I was not able to imagine any other life. I remember saying to myself, ‘If I can’t imagine a life where I’m out and free and feeling secure and confident and left alone, then I don’t even want to imagine any kind of a life in the future,’” says Peppermint.

Recently, Peppermint returned for season 2 of Netflix’s comedy “Survival of the Thickest.” She added some spice and kick to the first season in her role as a drag bar owner. This time around, her character moves center stage, as her engagement and wedding become a major plot line in the show. Her expanded role and high-profile trans representation come at just the right time.

“It’s the largest acting role I’ve ever had in a television show, which my acting degree thanks me. It feels right on time, in a day where they’re rolling back trans rights and wanting to reduce DEI and make sure that we are limited from encouraging companies, corporations, industries, and institutions from not only featuring us, but supporting us, or even talking about us, or even referencing us.

“It feels great to have something that we can offer up as resistance. You can try to moralize, but it’s tougher to legislate art. So it feels like this is right on time and I’m just really grateful that they gave me a chance and that they gave my character a chance to tell a greater story.

Peppermint’s expanded role also accompanies a boom in queer representation in Black-powered media. Networks like BET and Starz and producers like Tyler Perry, are now regularly showcasing queer Black folks in main story lines. What does Peppermint think is fueling this increased inclusion?

“Queer folks are not new and queer Black folks are not new and Black folks know that. Every Black person knows at least one person who is queer. We are everywhere. We have not always been at the forefront in a lot of storytelling, that’s true, and that’s the part that’s new. It’s Hollywood taking us from the place where they usually have held us Black, queer folks in the makeup room, or as the prostitute, as an extra—not that there’s anything wrong with sex work or playing a background performer. I’ve played the best of the hookers! But those [roles] are very limiting.

“Hollywood has not historically done and still does not do a very good job of, including the voices of the stories that they make money [on]. And I think they’re realizing [the need] to be inclusive of our stories and our experiences, because for a long time it was just our stories without our actual experiences. It’s also exciting. It’s dramatic. It makes money. And they’re seeing that. So I think they’re just dipping their toes in. I think that they’re going to realize that balance means having us there in the room.”

Peppermint’s activism is tireless. She has raised more than six figures for prominent LGBTQ rights groups, she continues to speak around the nation, appears regularly on major media outlets addressing trans and LGBTQ issues and has been honored by GLAAD, World of Wonder, Out magazine, Variety, Condé Nast and more—all while appearing on screen and onstage in a long list of credits.

Now, under the Trump administration, she doesn’t have time to take a breath.

“I wouldn’t be able to do it if it weren’t second nature for me. Of course, there are ups and downs with being involved with any social issue or conversation and politics. But I am, for now, energized by it. It’s not like I’m energized by like, ‘Ooh, I just love this subject!’ right? It’s like, ‘Oh, we’re still being discriminated against, we gotta go and fight.’

“That’s just what it is. I get energy because I feel like we are quite literally fighting for our lives. I know that is hyperbole in some regards, but they are limiting access to things like housing, healthcare, job security and not having identification. Passport regulations are being put in a blender.”

Peppermint also mentions her thoughts on the unfair mandates to remove trans service members and revoke the rights and resources from the veterans who worked their whole lives to fight for this country.

“When you strip all these things away, it makes it really difficult for people to have a life and I know that that is what they’re doing. When I look around and see that that is what is at stake, I certainly feel like I’m fighting for my life. And that’s energizing.

“The only thing that would be the most rewarding besides waking up in a utopia and suddenly we’re all equal and we’re not discriminating against each other—which probably is not happening this year—is to be able to be involved in a project like this, where we can create that world. It’s also being built by people who are a part of that story in real life and care about it in real life.”

Peppermint is clear on her point that now is the time for all of the letters of the LGBTQ community to come together. Everyone who is trans and queer should be joining the fight against the issues that affect us all.

“Just trust us and understand that our experiences are tied together. That is how and why we are discriminated against in the way[s] that we are. The people who discriminate—just like how they can’t really distinguish between somebody who’s Dominican and somebody who’s African American — you’re Black when you’re getting pulled over. We are discriminated against in much the same way. It’s the same with being trans or queer or gender non-conforming or bi, we all have our own experiences and they should be honored.

“When laws are being created to harm us, we need to band together, because none of y’all asses is gonna be able to stop them from getting rid of marriage equality—which is next. If you roll the tape back to three years ago when somebody was trying to ask me about drag queen bans on readings in school, I was saying they’re coming for trans rights, which comes for bodily autonomy and abortion rights, which comes for gay marriage rights. Those three things will be wiped out.

Peppermint doesn’t take a pause to get fired up and call gay folk out in their obligation to return the favor to the Black trans community.

She shares with us her final thoughts.

“You cis-gender homosexuals need to stand the fuck up and understand that we are standing in front of you. It’s very difficult to understand this and know this, but so many of the rights that we have were hard fought and won by protest and by people fighting very hard for them. And many of those people in every single instance from the suffrage movement, obviously Civil Rights, queer rights, the AIDS and HIV movement—Black queer people have been there the entire time. Trans people have always been a part of that story, including Stonewall. Yes, we are using different terminology. Yes, we have different lenses to view things through, but let me tell you, if you allow us to be sacrificed before you see us go off the side, you will realize that your foot is shackled to our left foot. So, you better stand the fuck up!”

Peppermint for president!

a&e features

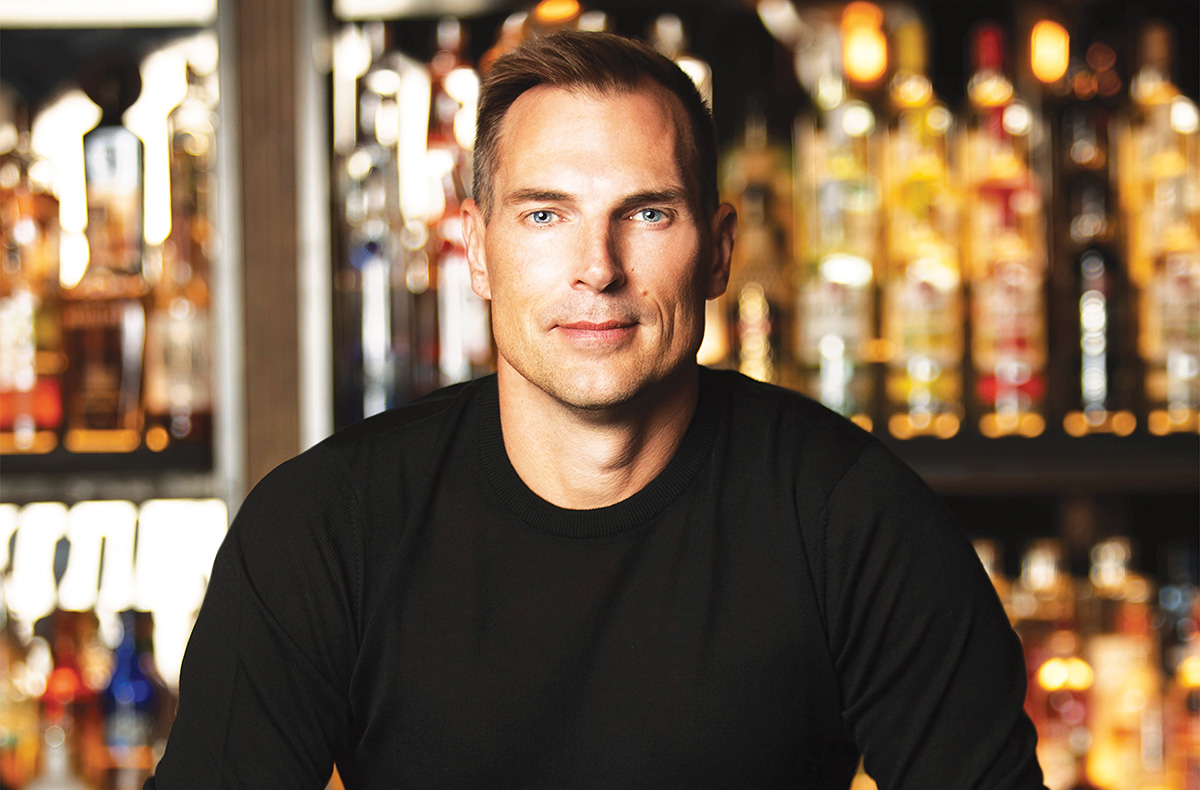

Tristan Schukraft on keeping queer spaces thriving

New owner of LA’s Abbey expands holdings to Fire Island, Mexico

LOS ANGELES — Like the chatter about Willy Wonka and his Chocolate Factory, the West Hollywood community here started to whisper about the man who was going to be taking over the world-famous Abbey, a landmark in Los Angeles’s queer nightlife scene. Rumors were put to rest when it was announced that entrepreneur Tristan Schukraft would be taking over the legacy created by Abbey founder David Cooley. All eyes are on him.

For those of us who were there for the re-opening of The Abbey, when the torch was officially passed, all qualms about the new regime went away as it was clear the club was in good hands and that the spirit behind the Abbey would forge on. Cher, Ricky Martin, Bianca del Rio, Jean Smart, and many other celebrities rubbed shoulders with veteran patrons, and the evening was magical and a throwback to the nightclub atmosphere pre-COVID.

The much-talked-about purchase of the Abbey was just the beginning for Schukraft. It was also announced that this business impresario was set to purchase the commercial district of Fire Island, as well as projects launching in Mexico and Puerto Rico. What was he up to? Tristan sat down with the Blade to chat about it all.

“We’re at a time right now when the last generation of LGBT entrepreneurs and founders are all in their 60s and they’re retiring. And if somebody doesn’t come in and buy these places, we’re going to lose our queer spaces.”

Tristan wasn’t looking for more projects, but he recounts what happened in Puerto Rico. The Atlantic Beach Hotel was the gay destination spot and the place to party on Sundays, facing the gay beach. A new owner came in and made it a straight hotel, effectively taking away a place of fellowship and history for the queer community. Thankfully, the property is gay again, now branded as the Tryst and part of Schukraft’s portfolio with locations in Puerto Vallarta and Fire Island.

“If that happens with the Abbey and West Hollywood, it’s like Bloomingdale’s in a mall. It’s kind of like a domino effect. So that’s really what it is all about for me at this point. It has become a passion project, and I think now more than ever, it’s really important.”

Tristan is fortifying spaces for the queer community at a time when the current administration is trying to silence the LGBTQ+ community. The timing is not lost on him.

“I thought my mission was important before, and in the last couple of months, it’s become even more important. I don’t know why there’s this effort to erase us from public life, but we’ve always been here. We’re going to continue to be here, and it brings even more energy and motivation for me to make sure the spaces that I have now and even additional venues are protected going in the future.”

The gay community is not always welcoming to fresh faces and new ideas. Schukraft’s takeover of the Abbey and Fire Island has not come without criticism. Who is this man, and how dare he create a monopoly? As Schukraft knows, there will always be mean girls ready to talk. In his eyes, if someone can come in and preserve and advance spaces for the queer community, why would we oppose that?

“I think the community should be really appreciative. We, as a community, now, more than ever, should stand together in solidarity and not pick each other apart.”

As far as the Abbey is concerned, Schukraft is excited about the changes to come. Being a perfectionist, he wants everything to be aligned, clean, and streamlined. There will be changes made to the DJ and dance booth, making way for a long list of celebrity pop-ups and performances. But his promise to the community is that it will continue to be the place to be, a place for the community to come together, for at least another 33 years.

“We’re going to build on the Abbey’s rich heritage as not only a place to go at night and party but a place to go in the afternoon and have lunch. That’s what David Cooley did that no others did before, is he brought the gay bar outside, and I love that.”

Even with talk of a possible decline in West Hollywood’s nightlife, Schukraft maintains that though the industry may have its challenges, especially since COVID, the Abbey and nightlife will continue to thrive and grow.

“I’m really encouraged by all the new ownership in [nightlife] because we need another generation to continue on. I’d be more concerned if everybody was still in their sixties and not letting go.”

In his opinion, apps like Grindr have not killed nightlife.

“Sometimes you like to order out, and sometimes you like to go out, and sometimes you like to order in, right? There’s nothing that really replaces that real human interaction, and more importantly, as we know, a lot of times our family is our friends, they’re our adopted family.

Sometimes you meet them online, but you really meet them going out to bars and meeting like-minded people. At the Abbey, every now and then, there’s that person who’s kind of building up that courage to go inside and has no wingman, doesn’t have any gay friends. So it’s really important that these spaces are fun, to eat, drink, and party. But they’re really important for the next generation to find their true identity and their new family.”

There has also been criticism that West Hollywood has become elitist and not accessible to everyone in the community. Schukraft believes otherwise. West Hollywood is a varied part of queer nightlife as a whole.

“West Hollywood used to be the only gay neighborhood, and now you’ve got Silver Lake and you’ve got parts of Downtown, which is really good because L.A., is a huge place. It’s nice to have different neighborhoods, and each offers its own flavor and personality.”

Staunch in his belief in his many projects, he is not afraid to talk about hot topics in the community, especially as they pertain to the Abbey. As anyone who goes to the Abbey on a busy night can attest to, the crowd is very diverse and inclusive. Some in the community have started to complain that gay bars are no longer for the gay community, but are succumbing to our straight visitors.

Schukraft explains: “We’re a victim of our own success. I think it’s great that we don’t need to hide in the dark shadows or in a hole-in-the-wall gay bar. I’m happy about the acceptance. I started Tryst Hotels, which is the first gay hotel. We’re not hetero-friendly, we’re not gay-friendly. We’re a gay hotel and everyone is welcome. I think as long as we don’t change our behavior or the environment in general at the Abbey, and if you want to party with us, the more than merrier.”

Schukraft’s message to the community?

“These are kind of dangerous times, right? The rights that we fought for are being taken away and are being challenged. We’re trying to be erased from public life. There could be mean girls, but we, as a community, need to stick together and unite, and make sure those protections and our identity aren’t erased. And even though you’re having a drink at a gay bar, and it seems insignificant, you’re supporting gay businesses and places for the next generation.”

a&e features

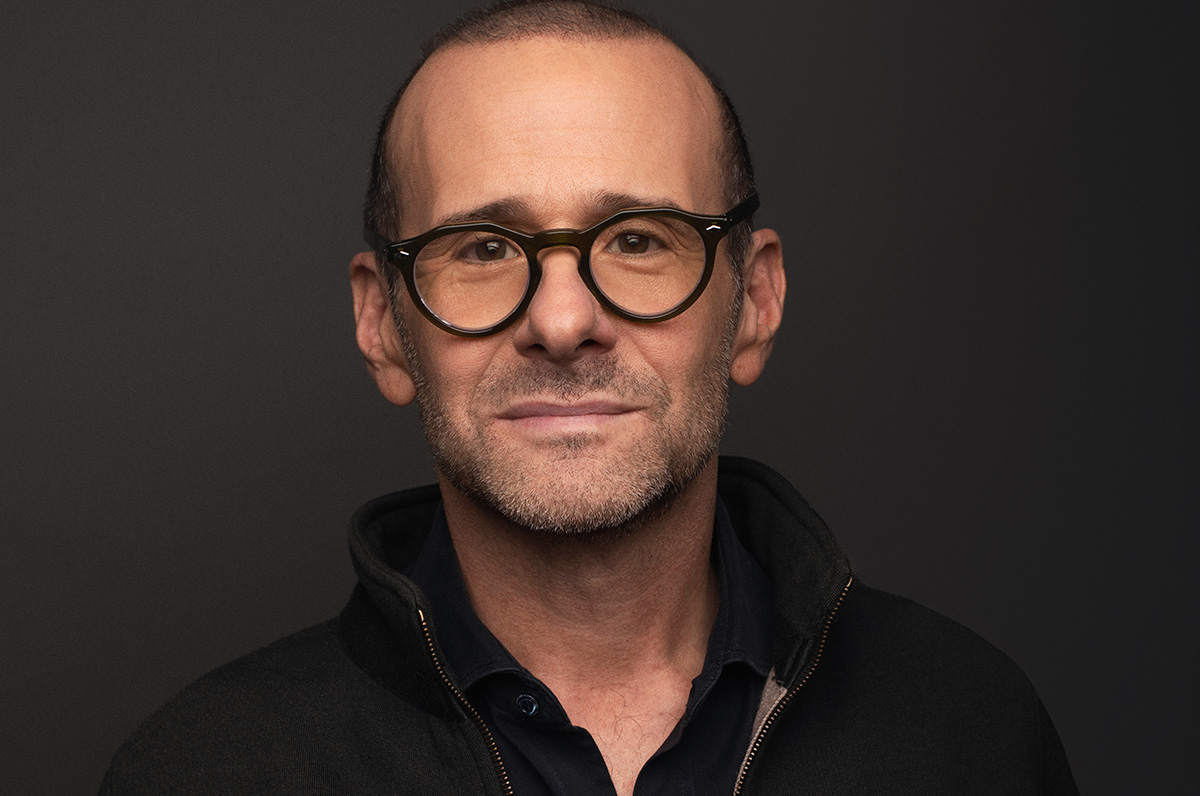

Creator Max Mutchnick on inspirations for ‘Mid-Century Modern’

Real-life friendships and loss inform plot of new Hulu show

It’s been a long time – maybe 25 years when “Will & Grace” debuted – since there’s been so much excitement about a new, queer sitcom premiering. “Mid-Century Modern,” which debuted on Hulu last week, is the creation of Max Mutchnick and David Kohan, the gay men who were also behind “Will & Grace.”

Set in Palm Springs, Calif., following the death of the one of their closest friends, three gay men gather to mourn. Swept up in the emotions of the moment, Bunny (Nathan Lane) suggests that Atlanta-based flight attendant Jerry (Matt Bomer) and New York-based fashion editor Arthur (Nathan Lee Graham) move into the mid-century modern home he shares with his mother Sybil (the late Linda Lavin). Over the course of the first season’s 10 episodes, hilarity ensues. That is, except for the episode in which they address Sybil’s passing. The three male leads are all fabulous, and the ensemble cast, including Pamela Adlon as Bunny’s sister Mindy, and the stellar line-up of guest stars, such as Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Vanessa Bayer, Richard Kind, and Cheri Oteri, keep humor buzzing. Shortly before the premiere of “Mid-Century Modern,” Mutchnick made time for an interview with the Blade.

BLADE: I’d like to begin by saying it’s always a delight to speak to a fellow Emerson College alum. In ways would you say that Emerson impacted your professional and creative life?

MAX MUTCHNICK: I think Emerson was the first place that reflected back to me that my voice, my thoughts were good, and they were worth listening to. I developed a confidence at Emerson that did not exist in my body and soul. It was a collection of a lot of things that took place in Boston, but I mean we can just put it all under the Emerson umbrella.

BLADE: Before “Will & Grace,” you co-created the NBC sitcom “Boston Common,” which starred fellow Emerson alum Anthony Clark. Is it important for you to maintain those kinds of alumni relationships?

MUTCHNICK: Because Emersonians are such scrappy little monkeys and they end up being everywhere in the world, you can’t help but work with someone from Emerson at some point in your career. I’m certainly more inclined to engage with someone from Emerson once I learn that they went to my alma mater. For me, it has much more to do with history and loyalty. I don’t think of myself as one of those guys that says, “Loyalty means a lot to me. I’m someone that really leans into history.” It’s just what my life and career turned out to be. The longer I worked with people and the more often I worked with them, the safer that I felt, which means that I was more creative and that’s the name of the game. I’ve got to be as comfortable as possible so I can be as creative as possible. If that means that a person from Emerson is in the room, so be it. (Costume designer) Lori Eskowitz would be the Emerson version. And then (writer and actor) Dan Bucatinsky would be another version. When I’m around them for a long time, that’s when the best stuff comes.

BLADE: Relationships are important. On that subject, your new Hulu sitcom “Mid-Century Modern” is about the longstanding friendship among three friends, Bunny (Nathan Lane), Jerry (Matt Bomer), and Arthur (Nathan Lee Graham). Do you have a friendship like the one shared by these three men?

MUTCHNICK: I’m absolutely engaged in a real version of what we’re projecting on the show. I have that in my life. I cannot say that I’m Jerry in any way, but the one thing that we do have in common is that in my group, I’m the young one. But I think that that’s very common in these families that we create. There’s usually a young one. Our culture is built on learning from our elders. I didn’t have a father growing up, so maybe that made me that much more inclined to seek out older, wiser, funnier, meaner friends. I mean the reason why you’re looking at a mouthful of straight, white teeth is because one of those old bitches sat across from me about 25 years ago at a diner and said, “Girl, your teeth are a disaster, and you need to get that fixed immediately.” What did I know? I was just a kid from Chicago with two nickels in my pocket. But I found three nickels and I went and had new teeth put in my head. But that came from one of my dearest in the group.

BLADE: Do you think that calling “Mid-Century Modern” a gay “Golden Girls” is a fair description?

MUTCHNICK: No. I think the gay “Golden Girls” was really just used as a tool to pitch the show quickly. We have an expression in town, which is “give me the elevator pitch,” because nobody has an attention span. The fastest way you can tell someone what David (Kohan) and I wanted to write, was to say, “It’s gay Golden Girls.” When you say that to somebody, then they say, “OK, sit down now, tell me more.” We did that and then we started to dive into the show and realized pretty quickly that it’s not the gay “Golden Girls.” No disrespect to the “Golden Girls.” It’s a masterpiece.

BLADE: “Mid-Century Modern” is set in Palm Springs. I’m based in Fort Lauderdale, a few blocks south of Wilton Manors, and I was wondering if that gay enclave was ever in consideration for the setting, or was it always going to be in Palm Springs?

MUTCHNICK: You just asked a really incredible question! Because, during COVID, Matt Bomer and I used to walk, because we live close by. We had a little walking group of a few gay gentlemen. On one of those walks, Matt proposed a comedy set in Wilton Manors. He said it would be great to title the show “Wilton Manors.” I will tell you that in the building blocks of what got us to “Mid-Century Modern,” Wilton Manors, and that suggestion from Matt Bomer on our COVID walks, was part of it.

BLADE: Is Sybil, played by the late Linda Lavin, modeled after a mother you know?

MUTCHNICK: Rhea Kohan (mother of David and Jenji). When we met with Linda for the first time over Zoom, when she was abroad, David and I explained to her that this was all based on Rhea Kohan. In fact, some of the lines that she (Sybil) speaks in the pilot are the words that Jenji Kohan spoke about her mother in her eulogy at the funeral because it really summed up what the character was all about. Yes, it’s very much based on someone.

BLADE: The Donny Osmond jokes in the second episode of “Mid-Century Modern” reminded me of the Barry Manilow “fanilows” on “Will & Grace.” Do you know if Donny is aware that he’s featured in the show?

MUTCHNICK: I don’t. To tell you the truth, the “fanilow” episode was written when I was not on the show. I was on a forced hiatus, thanks to Jeff Zucker. That was a show that I was not part of. We don’t really work that way. The Donny Osmond thing came more from Matt’s character being a Mormon, and also one of the writers. It’s very important to mention that the writing room at “Mid-Century Modern,” is (made up of) wonderful and diverse and colorful incredible humans – one of them is an old, white, Irish guy named Don Roos who’s brilliant…

BLADE: …he’s Dan Bucatinsky’s husband.

MUTCHNICK: Right! Dan is also part of the writing room. But I believe it was Don who had a thing for Donny, and that’s where it comes from. I don’t know if Donny has any awareness. The only thing I care about when we turn in an episode like that is I just want to hear from legal that we’re approved.

BLADE: “Mid-Century Modern” also includes opportunities for the singers in the cast. Linda Lavin sang the Jerome Kern/Ira Gershwin tune “Long Ago (And Far Away)” and Nathan Lane and the guys sang “He Had It Coming” from “Chicago.” Was it important to give them the chance to exercise those muscles?

MUTCHNICK: I don’t think it was. I think it really is just the managers’ choice. David Kohan and I like that kind of stuff, so we write that kind of stuff. But by no means was there an edict to write that. We know what our cast is capable of, and we will absolutely exploit that if we’re lucky enough to have a second season. I have a funky relationship with the song “Long Ago (And Far Away).” It doesn’t float my boat, but everybody else loved it. We run a meritocracy, and the best idea will out. That’s how that song ended up being in the show. I far prefer the recording of Linda singing “I’ll Be Seeing You” over her montage in episode eight, “Here’s To You, Mrs. Schneiderman.” We were just lucky that Linda had recorded that. That recording was something that she had done and sent to somebody during COVID because she was held up in her apartment. That’s what motivated her to make that video and send it. That’s how we were able to use that audio.

BLADE: Being on a streaming service like Hulu allows for characters to say things they might not get away with on network TV, including a foreskin joke, as well as Sybil’s propensity for cursing.

MUTCHNICK: And the third line in the show is about him looking like a “reluctant bottom.” I don’t think that’s something you’re going to see on ABC anytime soon. David and I liked the opportunity to open up the language of this show because it might possibly open the door to bringing people…I’m going to mix metaphors…into the tent that have never been there before. A generation that writes off a sitcom because that language and that type of comedy isn’t the way that they sound. One of the gifts of doing this show on Hulu is that we get to write dialogue that sounds a little bit more like you and I sound. As always, we don’t want to do anything just to do it.

BLADE: It didn’t feel that way.

MUTCHNICK: It’s there when it’s right. [Laughs] I want to have a shirt made with Linda’s line, as her mother always used to say, “Time is a cunt.”

BLADE: “Mid-Century Modern” also utilizes a lot of Jewish humor. How important is it for you to include that at this time when there is a measurable rise in anti-Semitism?

MUTCHNICK: I think it’s important, but I don’t think it’s the reason why we did it. We tried very hard to not write from a place of teaching or preaching. We really are just writing about the stuff that makes us laugh. One of the things that makes something better and something that you can invest in is if it’s more specific. We’re creating a character whose name is Bunny Schneiderman and his mother’s name is Sybil and they made their money in a family-run business, it gets Jewy, and we’re not going to shy away from it. But we’re definitely not going to address what’s going on in the world. That doesn’t mean I don’t find it very upsetting, but I’m writing always from the point of view of entertaining the largest number of people that I can every week.

BLADE: “Mid-Century Modern” has a fantastic roster of guest stars including Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Vanessa Bayer, Billie Lourd, Cheri Oteri, Richard Kind, Rhea Perlman, and Judd Hirsch. Are there plans to continue that in future seasons?

MUTCHNICK: Yes. As I keep saying, if we’re so lucky that we get to continue, I don’t want to do “The Love Boat.” Those are fine comic actors, so I don’t think it feels like that. But if we get to keep going, what I want to do is broaden the world because that gives us more to write about. I want to start to introduce characters that are auxiliary to the individuals. I want to start to meet Arthur’s family, so we can return to people. I want to introduce other neighbors, and different types of gay men because we come in so many different flavors. I think that we should do that only because I’m sure it’s what your life is and it’s what my life is. I’ve got a lot of different types. So, yes, we will be doing more.

BLADE: Finally, Linda Lavin passed away in December 2024, and in a later episode, the subject of her character Sybil’s passing is handled sensitively, including the humorous parts.

MUTCHNICK: We knew we had a tall order. We suffered an incredible loss in the middle of making this comedy. One of the reasons why I think this show works is because we are surrounded by a lot of really talented people. Jim Burrows and Ryan Murphy, to name two. Ryan played a very big role in telling us that it was important that we address this, that we address it immediately. That we show the world and the show goes on. That wasn’t my instinct because I was so inside the grief of losing a friend, because she really was. It wasn’t like one of those showbizzy-type relationships. And this is who she was, by the way, to everybody at the show. It was the way that we decided to go. Let’s write this now. Let’s not put this at the end of the season. Let’s not satellite her in. Let’s not “Darren Stevens” the character, which is something we would never do. The other thing that Jim Burrows made very clear to us was the import of the comedy. You have to write something that starts exactly in the place that these shows start. A set comedy piece that takes place in the kitchen. Because for David and me, as writers, we said we just want to tell the truth. That’s what we want to do with this episode and that’s the way that this will probably go best for us. The way that we’ve dealt with grief in our lives is with humor. That is the way that we framed writing this episode. We wanted it to be a chapter from our lives, and how we experience this loss and how we recover and move on.

-

Federal Government3 days ago

Federal Government3 days agoHHS to retire 988 crisis lifeline for LGBTQ youth

-

Opinions3 days ago

Opinions3 days agoDavid Hogg’s arrogant, self-indulgent stunt

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoD.C. police seek help in identifying suspect in anti-gay threats case

-

Virginia3 days ago

Virginia3 days agoGay talk show host wins GOP nom for Va. lieutenant guv