Arts & Entertainment

Netflix revisits ‘The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez’ in harrowing but essential docuseries

The name of Gabriel Fernandez still hangs heavy over the City of Los Angeles.

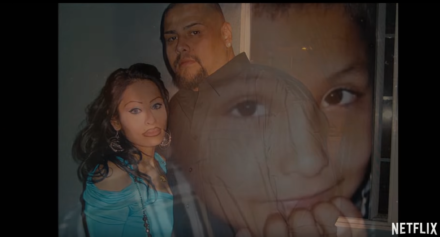

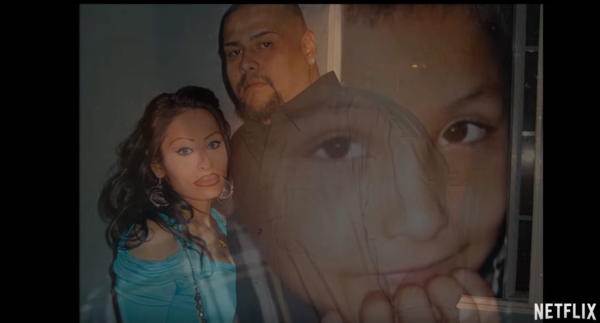

From the day the 8-year-old was found by Fire Department personnel on the floor of his Palmdale home after they responded to a 911 call from his mother, his story loomed large in the daily news. The paramedics had found Gabriel badly bruised and unresponsive, with profound injuries – broken ribs, a cracked skull, missing teeth, burnt skin, and BB bullets imbedded in his lungs and groin – that didn’t fit with the explanation they had been given for his condition. His mother, Pearl Sinthia Fernandez, and her boyfriend, Isauro Aguirre, claimed the boy had been injured by falling over a dresser and hitting his head. Gabriel was pronounced brain dead at the hospital on that same day, May 22, 2013; he was taken off life support and passed away two days later.

That tragic incident was the beginning of a seven-year ordeal for Gabriel’s family, his community, and the city itself. The child had been the victim of horrific and systematic abuse, perpetrated by his mother and Aguirre and allegedly motivated at least partly by Aguirre’s belief that the boy was gay; worse yet, other family members, as well as Gabriel’s teacher, had notified Children and Family Services multiple times over concerns that he was being mistreated, yet social workers had found, in every case but one, that their reports were unfounded – despite what seemed in retrospect to be clear indications to the contrary.

Fernandez and Aguirre were charged with first-degree murder in the death of Gabriel, with a special circumstance for torture, and in an unprecedented move, county prosecutors also charged four county social workers with one felony count each of child abuse and falsifying records.

The case dominated headlines as the ensuing investigation and court proceedings revealed ever more disturbing details about Gabriel’s short life and cruel death. The prosecution sought the death penalty for both of the perpetrators, who admitted to killing the child but claimed it had not been a pre-meditated act. Finally, in 2018, Aguirre was found guilty of the first degree changes and sentenced to death; Fernandez avoided the death penalty by agreeing to plead guilty.

In January of 2020, the charges against the four social workers were thrown out by a three-justice panel of the 2nd District Court of Appeal.

Now, Netflix is set to unveil “The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez,” a six-part docuseries which examines the case as it was laid out by LA County prosecutors, as well as chronicling journalistic efforts to track the weaknesses within the government agencies devoted to children’s welfare that permitted such a heartbreaking act to take place. Directed by documentarian Brian Knappenberger (“Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press”), it’s a gripping (and grim) deep dive into the case that may well be the most intense and upsetting true crime series the streaming network has produced so far.

Casting lead prosecutor Jon Hatami in the role of avenging hero, Knappenberger’s chronicle of the court case carefully avoids straying into sensationalism without shying away from the gruesome facts of Gabriel’s life. Through trial footage, interviews, and footage shot specifically for the show, we are given as comprehensive a look at the story as is possible in six hours of television, with the benefit and clarity of hindsight to assist in offering an overarching view of not only what happened, but of the systemic problems that led to a failure by those charged with protecting at-risk children to prevent the worst from happening to Gabriel. Perhaps most effectively, it repeatedly reminds us, through photos, footage, and the words of those who knew him, that Gabriel was a kind, loving, and gentle child who deserved much better treatment at the hands of those who should have been his caretakers.

As for the assertion that homophobia was a factor in Aguirre’s brutal beating and killing of his de-facto stepson, it doesn’t offer a lot of detail – prosecutors chose not to pursue a hate crime charge for strategic reasons, so that angle was only supplemental in proving a case for pre-meditation based solely on factual evidence – but it makes sure we hear about it in both through Hatami’s court statements and from the mouths of family members, who assert that Gabriel had been taken by the couple from his uncle and same-sex partner (previously given custody when his mother “didn’t want him” at birth) because they didn’t approve of a child being raised by gay parents. By all reports, Gabriel experienced the happiest and most supportive environment of his short life when he lived with them.

The Netflix series spends considerable time hammering home the shocking reality of the violence suffered by little Gabriel (described by Los Angeles Judge George G. Lomeli at Aguirre’s sentencing as “horrendous, inhumane and nothing short of evil”), and rightly so; to do anything less would be a disservice to his memory. Once it has done that, however, it sets its sights on the deeply shrouded county bureaucracy of Child and Family Services, the uniquely autonomous and powerful agency that oversees child welfare, and paints perhaps an even more disturbing picture of an organization overworked, understaffed, hamstrung by the financial priorities of privatization, and cloistered in a stubborn veil of secrecy that resisted not just inquiries from the press but from prosecutors as well. It also makes clear that law enforcement officials were well aware of the prior history of reported abuse in the Fernandez home before that fateful day when Gabriel’s life came to an end.

At the same time, Knappenberger takes care to offer a balanced view of the more complex ethical issues at the core of the case. His coverage of the four accused social workers, singled out in the minds of many as scapegoats by county officials looking for a means of damage control, is fair and compassionate, offering a glimpse at the daunting pressure and moral quandaries that face such civil servants; that it never quite lets them off the hook for the choices they made in handling Gabriel’s situation before it was too late is more testament to the journalistic integrity to which the series aspires.

Though the case of Gabriel Fernandez made the news nationwide, many outside of Los Angeles itself will likely only have passing familiarity with what happened. With “The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez,” Netflix is ensuring that Gabriel’s heartbreaking story will be known by millions – and while some may be hesitant to watch due to the disturbing nature of its conflict, it’s a show that demands to be seen. It reminds us, in no uncertain terms, that there are monsters in the world; but it also reminds us that for every Isauro Aguirre or Pearl Fernandez, there is also a Jon Hatami – someone who will stand up to fight for justice in the name of those who have suffered at their hands. Perhaps most important, it reminds us there is still much work to be done in perfecting the systems we have in place to serve our children – and that unrelenting, powerful journalism is still the best tool we have for holding those systems accountable.

“The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez” premieres on Wednesday, February 26, on Netflix. You can watch the trailer below.

The Gay Men’s Chorus of Washington perform “The Holiday Show” at Lincoln Theatre (1215 U St., N.W.). Visit gmcw.org for tickets and showtimes.

(Washington Blade photos by Michael Key)

Santa will be very relieved.

You’ve taken most of the burden off him by making a list and checking it twice on his behalf. The gift-buying in your house is almost done – except for those few people who are just so darn hard to buy for. So what do you give to the person who has (almost) everything? You give them a good book, like maybe one of these.

Memoir and biography

The person who loves digging into a multi-level memoir will be happy unwrapping “Blessings and Disasters: A Story of Alabama” by Alexis Okeowo (Henry Holt). It’s a memoir about growing up Black in what was once practically ground zero for the Confederacy. It’s about inequality, it busts stereotypes, and yet it still oozes love of place. You can’t go wrong if you wrap it up with “Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore” by Ashley D. Farmer (Pantheon). It’s a chunky book with a memoir with meaning and plenty of thought.

For the giftee on your list who loves to laugh, wrap up “In My Remaining Years” by Jean Grae (Flatiron Books). It’s part memoir, part comedy, a look back at the late-last-century, part how-did-you-get-to-middle-age-already? and all fun. Wrap it up with “Here We Go: Lessons for Living Fearlessly from Two Traveling Nanas” by Eleanor Hamby and Dr. Sandra Hazellip with Elisa Petrini (Viking). It’s about the adventures of two 80-something best friends who seize life by the horns – something your giftee should do, too.

If there’ll be someone at your holiday table who’s finally coming home this year, wrap up “How I Found Myself in the Midwest” by Steve Grove (Simon & Schuster). It’s the story of a Silicon Valley worker who gives up his job and moves with his family to Minnesota, which was once home to him. That was around the time the pandemic hit, George Floyd was murdered, and life in general had been thrown into chaos. How does someone reconcile what was with what is now? Pair it with “Homestand: Small Town Baseball and the Fight for the Soul of America” by Will Bardenwerper (Doubleday). It’s set in New York and but isn’t that small-town feel universal, no matter where it comes from?

Won’t the adventurer on your list be happy when they unwrap “I Live Underwater” by Max Gene Nohl (University of Wisconsin Press)? They will, when they realize that this book is by a former deep-sea diver, treasure hunter, and all-around daredevil who changed the way we look for things under water. Nohl died more than 60 years ago, but his never-before-published memoir is fresh and relevant and will be a fun read for the right person.

If celeb bios are your giftee’s thing, then look for “The Luckiest” by Kelly Cervantes (BenBella Books). It’s the Midwest-to-New-York-City story of an actress and her life, her marriage, and what she did when tragedy hit. Filled with grace, it’s a winner.

Your music lover won’t want to open any other gifts if you give “Only God Can Judge Me: The Many Lives of Tupac Shakur” by Jeff Pearlman (Mariner Books). It’s the story of the life, death, and everything in-between about this iconic performer, including the mythology that he left behind. Has it been three decades since Tupac died? It has, but your music lover never forgets. Wrap it up with “Point Blank (Quick Studies)” by Bob Dylan, text by Eddie Gorodetsky, Lucy Sante, and Jackie Hamilton (Simon & Schuster), a book of Dylan’s drawings and artwork. This is a very nice coffee-table size book that will be absolutely perfect for fans of the great singer and for folks who love art.

For the giftee who’s concerned with their fellow man, “The Lost and the Found: A True Story of Homelessness, Found Family and Second Chances” by Kevin Fagan (One Signal / Atria) may be the book to give. It’s a story of two “unhoused” people in San Francisco, one of the country’s wealthiest cities, and their struggles. There’s hope in this book, but also trouble and your giftee will love it.

For the person on your list who suffered loss this year, give “Pine Melody” by Stacey Meadows (Independently Published), a memoir of loss, grief, and healing while remembering the person gone.

LGBTQ fiction

For the mystery lover who wants something different, try “Crime Ink: Iconic,” edited by John Copenhaver and Salem West (Bywater Books), a collection of short stories inspired by “queer legends” and allies you know. Psychological thrillers, creepy crime, cozies, they’re here.

Novel lovers will want to curl up this winter with “Middle Spoon” by Alejandro Varela (Viking), a book about a man who appears to have it all, until his heart is broken and the fix for it is one he doesn’t quite understand and neither does anyone he loves.

LGBTQ studies – nonfiction

For the young man who’s struggling with issues of gender, “Before They Were Men” by Jacob Tobia (Harmony Books) might be a good gift this year. These essays on manhood in today’s world works to widen our conversations on the role politics and feminism play in understanding masculinity and how it’s time we open our minds.

If there’s someone on your gift list who had a tough growing-up (didn’t we all?), then wrap up “I’m Prancing as Fast as I Can” by Jon Kinnally (Permuted Press / Simon & Schuster). Kinnally was once an awkward kid but he grew up to be a writer for TV shows you’ll recognize. You can’t go wrong gifting a story like that. Better idea: wrap it up with “So Gay for You: Friendship, Found Family, & The Show That Started It All” by Leisha Hailey & Kate Moennig (St. Martin’s Press), a book about a little TV show that launched a BFF-ship.

Who doesn’t have a giftee who loves music? You sure do, so wrap up “The Secret Public: How Music Moved Queer Culture from the Margins to the Mainstream” by Jon Savage (Liveright). Nobody has to tell your giftee that queer folk left their mark on music, but they’ll love reading the stories in this book and knowing what they didn’t know.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Theater

Studio’s ‘Mother Play’ draws from lesbian playwright’s past

A poignant memory piece laced with sadness and wry laughs

‘The Mother Play’

Through Jan. 4

Studio Theatre

1501 14th St., N.W.

$42 – $112

Studiotheatre.org

“The Mother Play” isn’t the first work by Pulitzer Prize-winning lesbian playwright Paula Vogel that draws from her past. It’s just the most recent.

Currently enjoying an extended run at Studio Theatre, “The Mother Play,” (also known as “The Mother Play: A Play in Five Evictions,” or more simply, “Mother Play”) is a 90-minute powerful and poignant memory piece laced with sadness and wry laughs.

The mother in question is Phyllis Herman (played exquisitely by Kate Eastwood Norris), a divorced government secretary bringing up two children under difficult circumstances. When we meet them it’s 1964 and the family is living in a depressing subterranean apartment adjacent to the building’s trash room.

Phyllis isn’t exactly cut out for single motherhood; an alcoholic chain-smoker with two gay offspring, Carl and Martha, both in their early teens, she seems beyond her depth.

In spite (or because of) the challenges, things are never dull in the Herman home. Phyllis is warring with landlords, drinking, or involved in some other domestic intrigue. At the same time, Carl is glued to books by authors like Jane Austen, and queer novelist Lytton Strachey, while Martha is charged with topping off mother’s drinks, not a mean feat.

Despite having an emotionally and physically withholding parent, adolescent Martha is finding her way. Fortunately, she has nurturing older brother Carl (the excellent Stanley Bahorek) who introduces her to queer classics like “The Well of Loneliness” by Radclyffe Hall, and encourages Martha to pursue lofty learning goals.

Zoe Mann’s Martha is just how you might imagine the young Vogel – bright, searching, and a tad awkward.

As the play moves through the decades, Martha becomes an increasingly confident young lesbian before sliding comfortably into early middle age. Over time, her attitude toward her mother becomes more sympathetic. It’s a convincing and pleasing performance.

Phyllis is big on appearances, mainly her own. She has good taste and a sharp eye for thrift store and Goodwill finds including Chanel or a Von Furstenberg wrap dress (which looks smashing on Eastwood Norris, by the way), crowned with the blonde wig of the moment.

Time and place figure heavily into Vogel’s play. The setting is specific: “A series of apartments in Prince George’s and Montgomery County from 1964 to the 21st century, from subbasement custodial units that would now be Section 8 housing to 3-bedroom units.”

Krit Robinson’s cunning set allows for quick costume and prop changes as decades seamlessly move from one to the next. And if by magic, projection designer Shawn Boyle periodically covers the walls with scurrying roaches, a persistent problem for these renters.

Margot Bordelon directs with sensitivity and nuance. Her take on Vogel’s tragicomedy hits all the marks.

Near the play’s end, there’s a scene sometimes referred to as “The Phyllis Ballet.” Here, mother sits onstage silently in front of her dressing table mirror. She is removed of artifice and oozes a mixture of vulnerability but not without some strength. It’s longish for a wordless scene, but Bordelon has paced it perfectly.

When Martha arranges a night of family fun with mom and now out and proud brother at Lost and Found (the legendary D.C. gay disco), the plan backfires spectacularly. Not long after, Phyllis’ desire for outside approval resurfaces tenfold, evidenced by extreme discomfort when Carl, her favorite child, becomes visibly ill with HIV/AIDS symptoms.

Other semi-autobiographical plays from the DMV native’s oeuvre include “The Baltimore Waltz,” a darkly funny, yet moving piece written in memory of her brother (Carl Vogel), who died of AIDS in 1988. The playwright additionally wrote “How I Learned to Drive,” an acclaimed play heavily inspired by her own experiences with sexual abuse as a teenager.

“The Mother Play” made its debut on Broadway in 2024, featuring Jessica Lange in the eponymous role, earning her a Tony Award nomination.

Like other real-life matriarch inspired characters (Mary Tyrone, Amanda Wingfield, Violet Weston to name a few) Phyllis Herman seems poised to join that pantheon of complicated, women.