Arts & Entertainment

Coronavirus claims iconic LGBTQ playwright Terrence McNally

Succumbed to complications from COVID-19 at the age of 81

The theatre community, already hard hit by the coronavirus pandemic, has been dealt a painful blow with the news that Terrence McNally, the 4-time Tony winning playwright whose work portrayed a rich range of human emotional experience and broke barriers in its depiction of gay life, has succumbed to complications from COVID-19 at the age of 81.

McNally, who was a survivor of lung cancer and lived with chronic COPD, died on Tuesday at the Sarasota Memorial Hospital in Florida.

Born in St. Petersburg, Florida, McNally grew up in Corpus Christi, Texas, where his New York-born parents instilled in him a love for theatre from an early age. After earning a BA at Columbia University in 1960, he developed a relationship with author John Steinbeck, who hired the young playwright to accompany his family on a worldwide cruise as a tutor to his teenage sons. Steinbeck would later enlist McNally to write the libretto for “Here’s Where I Belong,” a musical stage adaptation of the author’s classic novel, “East of Eden.”

During his early years in New York, McNally also developed a relationship with fellow playwright Edward Albee, whom he met when the two shared a cab; the pair were essentially a couple for four years, during the period in which Albee wrote “The American Dream” and “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?,” two of his most important works. It was a romance that would cast a shadow over McNally’s early career, when some critics dismissed him as “the boyfriend” after the premiere of his Broadway debut, “And Things That Go Bump in the Night.” The play, which was McNally’s first effort in three acts, flopped due to poor initial reviews – attributed by author Boze Hadleigh in his book, “Who’s Afraid of Terrence McNally,” to homophobia from conservative New York critics – even after subsequent critical reaction and audience response proved to be more favorable.

After the failure of his initial foray onto the Broadway stage, McNally rebounded with an acclaimed one-act, “Next,” which featured James Coco as a middle-aged man mistakenly drafted into the army and was directed by Elaine May, and was presented Off-Broadway in a double bill with May’s “Adaptation” in 1967. Several other one-acts followed, and the playwright gained a reputation for tackling edgy subject matter with sharp social commentary, biting dialogue, and farcical situations. He also attracted early controversy for featuring onstage nudity (from actress Sally Kirkland) for the entire length of his kidnapping drama, “Sweet Eros.”

Success came his way in the seventies, when he racked up an Obie award for 1974’s “Bad Habits,” and a Broadway hit with “The Ritz,” a risqué farce set in a gay bathhouse where a straight middle-aged business man unwittingly goes into hiding to escape his wife’s murderous mafioso brother. Adapted from his own earlier play, “The Tubs,” it was subsequently turned into a 1976 film version (directed by “A Hard Day’s Night” filmmaker Richard Lester), starring original stage cast members Jack Weston, Jerry Stiller, F. Murray Abraham, and Rita Moreno (reprising her Tony-winning role as bathhouse chanteuse Googie Gomez), as well as featuring a blonde-dyed Treat Williams in an early appearance as an undercover cop.

After another series of career setbacks, McNally rebounded again in the eighties with more Off-Broadway acclaim for his play, “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune,” which starred Kathy Bates and F. Murray Abraham. The playwright has said that it was his first work after becoming sober, telling the New York Times in 2019, “There was certainly a change in my work. It’s hard to know who you are if you’re drunk all the time. It clouds your thinking. I started thinking more about my people — my characters.”

It was in the nineties, however, that McNally blossomed into a master playwright, with plays like “Lips Together, Teeth Apart,” which placed AIDS squarely in the backdrop of its story about two married couples spending a weekend on Fire Island, and “Master Class,” a tour-de-force one-woman show about Maria Callas which featured Zoe Caldwell in a widely acclaimed performance.

It was also during this period that McNally wrote “Love! Valour! Compassion!,” an expansive play about a group of gay friends who spend three successive holiday weekends over the course of a summer together at a lake house in upstate New York. Transferring to Broadway after a successful debut at the Manhattan Theatre Club – with which McNally had a long association, and where he developed several of his important works – in a production directed by Joe Mantello, it was a pastoral, introspective, Chekhovian drama that offered deeply-drawn, non-stereotypical portrayals of gay characters confronting the various issues in their lives and their relationships; it was also a snapshot of life at the height of the AIDS crisis, exploring the ways in which the spectre of the disease was an unavoidable part of day-to-day life that encroached upon every aspect of gay experience. McNally’s script, bolstered by the richly human performances of an ensemble cast that included Nathan Lane, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Anthony Heald, and Justin Kirk, countered the potential for moroseness with warmth and humor, and the play is now widely seen, alongside plays such as Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” and Paul Rudnick’s “Jeffrey,” as one of the most important theatrical works of the AIDS era. A film version in 1997 reunited most of the original stage cast, though the notably straight Jason Alexander replaced Lane in the role of Buzz, the most outwardly flamboyant of the play’s eight gay characters.

It was in the nineties when McNally also established himself as an important figure in the musical genre, contributing the libretto for John Kander and Fred Ebb’s “The Rink” (a short-lived musical drama starring Chita Rivera and Liza Minnelli) before going on to collaborate again with the legendary score composers on “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” their musical version of the Manuel Puig novel about the unlikely friendship that develops between a political revolutionary and a gay window dresser as they share a cell in a Mexican prison. The musical (which also starred Rivera) was a smash hit and won McNally his first Tony (Best Book for a Musical) in 1993.

In 1998, he won another Tony in the same category for the libretto of “Ragtime,” a widely-acclaimed musical adaptation of the E.L. Doctorow novel exploring racism against the backdrop of the turn of the 20th Century with a score by Stephen Flaherty and Lynne Ahrens.

His other two Tonys were for “Love! Valour! Compassion!” and “Master Class,” in 1995 and 1996, respectively.

In his later career, McNally courted controversy once again with “Corpus Christi,” a 1998 “passion play” that queered the biblical story of Jesus and the Apostles by reimagining them as gay men living in modern-day Texas. At the time, the production was met with protests (McNally himself received death threats), although reviewers found its content to be surprisingly uncontroversial, with Jason Zinoman of the New York Times calling it “earnest and reverent” and “more personal than political.”

Other notable dramatic works included “The Lisbon Traviata,”

“It’s Only A Play,” “A Perfect Ganesh,” “The Stendahl Syndrome,” “Mothers and

Sons,” and his last, 2018’s “Fire and Air.” He also wrote librettos for the musicals

“The Full Monty,” “A Man of No Importance,” “Anastasia,” and “The Visit” (also

with Kander and Ebb, and also starring Rivera), and for the operas “Dead Man Walking,”

“Three Decembers,” and “Great Scott.”

He also wrote for television, including an Emmy-winning teleplay for the 1988 AIDS

drama “Andre’s Mother.” For film, he wrote the screenplays for the film

adaptations of his plays, “The Ritz,” “Love! Valour! Compassion!,” and “Frankie

and Johnny at the Clair de Lune” (retitled as simply “Frankie and Johnny”).

Besides his Tony and Emmy wins, he also earned three Drama Desk Awards, two Lucille Lortel Awards, and two Obies, as well as a Pulitzer Prize nomination.

In addition to his four competitive Tonys, he was awarded a Special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2019.

He was also the recipient of two Guggenheim Fellowships and a Rockefeller Grant.

McNally is survived by his husband, Thomas Kirdahy, whom he wed in 2010 after a long relationship. Other survivors include a brother Peter McNally, and his wife Vicky McNally, along with their children and grandchildren; also listed among the survivors are Mother-in-Law Joan Kirdahy, sister/brother-in-laws Carol Kirdahy, Kevin Kirdahy, James Kirdahy, Kathleen Kirdahy Kay, and Neil Kirdahy.

Books

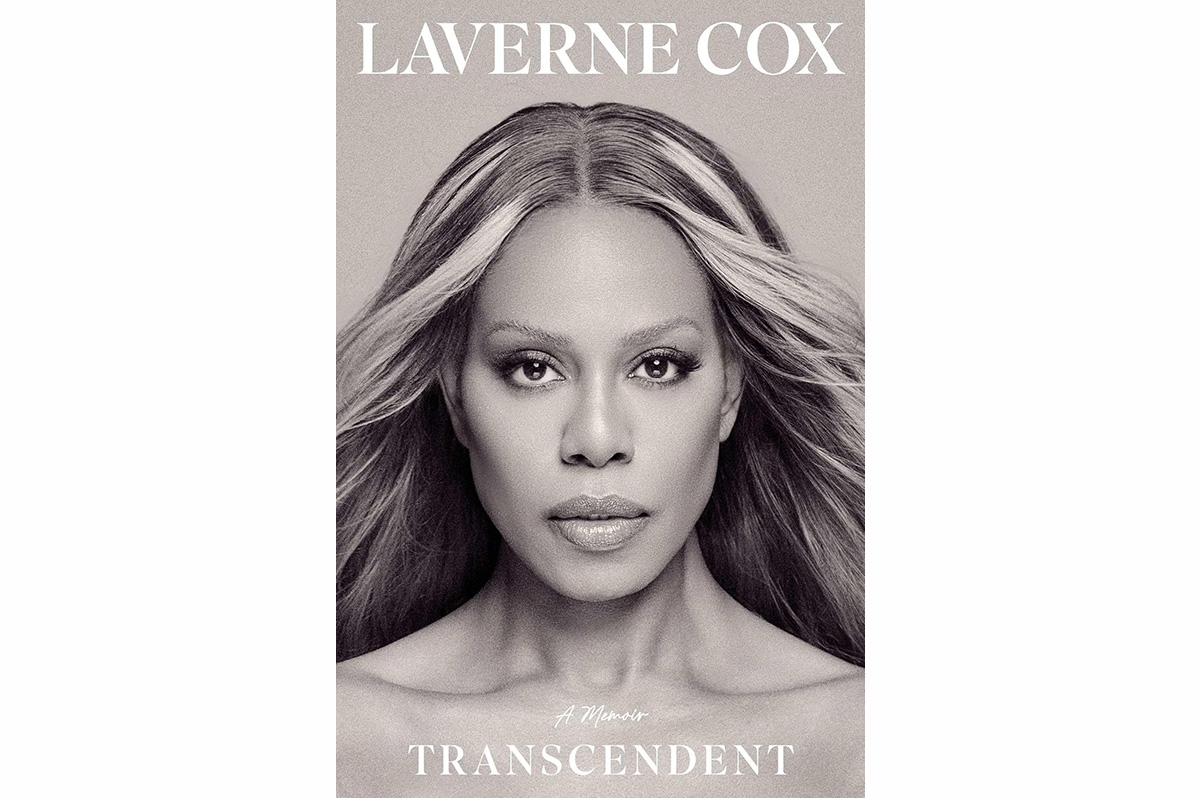

Laverne Cox, Liza Minnelli among authors with new books

A tome for every taste this reading season

Spring is a great time to think about vacations, spring break, lunch on the patio, or an afternoon in the park. You’ll want to bring one (or all!) of these great new books.

So let’s start here: What are you up for? How about a great new novel?

If you’re a mystery fan, you’ll want to make reservations to visit “Disaster Gay Detective Agency” by Lev AC Rosen (Poisoned Pen Press, June 2). It’s a whodunit featuring a group of gay roommates, one of whom is a swoony romantic. Add a mysterious man who disappears and a murder, of course, and you’ve got the novel you need for the beach.

Don’t discount young adult books, if you want something light to read this spring. “What Happened to Those Girls” by Carlyn Greenwald (Sourcebooks Fire, June 30) is a thriller about mean girls and a camping trip that goes terribly, bloodily wrong. Meant for teens ages 14 and up, young adult books are breezier and lighter fare for the busy grown-up reader.

If you loved “Boyfriend Material” and “Husband Material,” you’ll be eager for the next installment from author Alexis Hall. “Father Material” (Sourcebooks Casablanca, June 2) takes Luc and Oliver to the next step. First was dating. Then was marriage. Is it time for the sound of pitter-patter on the kitchen floor?

Maybe something even lighter? Then how about a book of essays – like “The Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Gay” bycomedian and writer Eliot Glazer (Gallery Books, Aug. 11). It’s a book of essays on being gay today, the irritations, the joys, and fitting in. Be aware that these essays may contain a bit of spice – but isn’t that what you want for your reading pleasure anyhow, hmmm?

But okay, let’s say you want something with a little more heft to it. How about a biography?

Look for “Transcendant” by Laverne Cox (Gallery Books, June 9), or “Kids, Wait Till You Hear This” by Liza Minnelli (Grand Central Publishing, March 10), and “Every Inch a Lady” by Audrey Smaltz with Alina Mitchell (Amistad, July 14). Keep your eyes open for “Without Prejudice: My Life as a Gay Judge” by Harvey Brownstone (ECW Press, May 26) or “The Double Dutch Fuss” by Phill Branch (Amistad, June 2).

Then again, maybe you want some history, or something different.

So here: look for “Queer Saints: A Radical Guide to Magic, Miracles, and Modern Intercession” by Antonio Pagliarulo (Weiser, June 1) for a little bit of faith-based gay. Music lovers will want “Mighty Real: A History of LGBTQ Music, 1969-2000” by Barry Walters (Viking, May 12). Activists will want “In the Arms of Mountains: A Memoir of Land, Love, and Queer Resistance in Red America” byformer Idaho state Sen. Cole Nicole LeFavour (Beacon Press, May 26).

And if these books aren’t enough, then be sure to check with your favorite bookseller or librarian. They’ll have exactly what you’re in the mood to read. They’ll find what you need for that patio, beach towel, or easy chair.

Music & Concerts

Gaga, Cardi B, and more to grace D.C. stages this spring

Shake off your winter doldrums at a local concert

D.C. shakes off its winter blues this spring as the music scene pops off. We all know the big star is coming: Lady Gaga will perform at Capital One Arena on March 23. But plenty of other stars, big and small, will grace D.C. stages, including many LGBTQ and ally artists.

March

3/15, 9:30 Club, St. Lucia – Indie electronic music project known for its synth-pop sound, which blends ‘80s influences with electronic and indie rock elements.

3/31, Lincoln Theatre, Perfume Genius – Indie/pop singer/songwriter Mike Hadreas, also known as Perfume Genius, has toured with a full band, but he is stripping things back for this tour.

April

4/8, Capital One, Cardi B. Cardi B, from New York, unapologetic and proud, is the first solo female artist to win the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. This year, she’s on her Little Miss Drama Tour, in support of her second studio album, “Am I the Drama?”

4/13, Lincoln Theatre, The Naked Magicians. Australia’s The Naked Magicians are two performers who deliver live magic and laughs while wearing nothing but a top hat and a smile.

4/18, Capital One, Florence and the Machine. Longstanding indie rock back from Great Britain, much-loved for lead singer Florence’s powerful vocals. On their Everybody Scream Tour.

4/16, Capital One, Demi Lovato. Singer/songwriter from Texas, who came out as nonbinary, is traveling on her “It’s Not That Deep Tour.”

4/21, The Anthem, Calum Scott. Platinum-selling gay singer/songwriter Calum Scott released his latest project, Avenoir, last year. Scott rose to fame in 2015 after competing on Britain’s Got Talent, where he performed a cover of Robyn’s hit “Dancing on My Own“.

4/26, Atlantis, Caroline Kingsbury. American queer pop musician from Los Angeles. She released her debut album in 2021, and has two additional EPs. She’s played Lollapalooza 2025 and All Things Go 2025, as well as gone on a co-headlining U.S. tour with MARIS. Shock Treatment is her latest EP.

4/26, Anthem, Raye. This bisexual artist, known for her current chart-topping “”Where Is My Husband!” single, blends pop, jazz, R&B, and more.

4/30, Union Stage, Daya. This bisexual singer/songwriter is on her “Til Every Petal Drops Tour,” touring the album of the same name that was released last year.

May

5/1, The Anthem, Joost Klein. Eurovision comes to D.C. in Joost Klein: Originally a Youtuber, he was selected to represent the Netherlands at Eurovision in 2024 with his song “Europapa.” He released a new album on New Year’s Day.

5/1, Fillmore, MIKA. MIKA is on his Spinning Out Tour. Born in Beirut and raised in both Paris and London, MIKA sings in multiple languages and has co-hosted Eurovision.

5/7, 9:30 Club, COBRAH. Clara Christensen, is a Swedish singer, songwriter, record producer, and club queen, making electronic dance music.

5/19, Atlantis, Grace Ives. New York-born singer/songwriter, known for her high-energy synth/electronic, bedroom-pop-style music.

June

6/2, The Anthem, James Blake. English crooner got big from his self-titled debut album in 2011. He won two Grammys and just released his 7th album,Trying Times, in March.

It’s surely a sign of the times that this year’s spring preview of upcoming screen entertainment doesn’t hold nearly as much boldly out-and-proud queer content as we would like – but then again, there are only a small handful of noteworthy titles overall – especially on the big screen, where, just like any year, the top-grade content is being saved for summer.

Even so, we’ve managed to put together a list of the movies and shows on the horizon that offer a much-needed taste of the rainbow; a mix that includes returning favorites, “don’t-miss” events, and a few promising big screen crowd-pleasers, it should keep you occupied until the summer season brings a fresh new crop of (hopeful) blockbusters with it.

Scarpetta (Prime Video, March 11). Proving once again that she’s on a quest to accumulate more screen appearances than any other actor in history, Nicole Kidman returns for another star turn by way of this true-crime-ish mystery series, adapted from the bestselling “Kay Scarpetta” novels by lesbian author Patrica Cornwell, as a “brilliant and beautiful” forensic pathologist who uses her knowledge to solve murders. If that’s not enough to draw you in, her co-stars include fellow Oscar-winners Jamie Lee Curtis (as her feisty older sister) and Ariana DuBose (as her nosy lesbian niece), as well as Bobby Cannavale and Simon Baker.

It’s Dorothy! (Peacock, March 13). Filmmaker Jeffrey McHale first won our attention with his fun and insightful “Showgirls” documentary, and now he’s back with a look at perhaps the ultimate queer icon in popular culture: none other than Dorothy Gale, that Kansas farm girl who taught us all that “there’s no place like home” in L. Frank Baum’s classic novel “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” and its sequels – and of course, in a certain movie adaptation starring Judy Garland. Charting the journey of the fictional heroine across a century of cultural reiterations – on the page, the stage, the screen, and beyond – with a mix of archival material, artistic interpretations, and commentary from queer and queer-friendly voices such as John Waters, Rufus Wainwright, and Lena Waithe, it’s sure to be required viewing for every “Friend of Dorothy” – and all of their friends, too.

The 37th Annual GLAAD Media Awards (Hulu, March 21). Sure, it’s already happened and you already knew (or can find out with a few quick taps of your phone screen) who and what the winners were – but, hey, we already know that the Oscars aren’t going to offer much in the way of queer victories (since there are only a small handful of queer nominees), so why not plan to watch the GLAAD ceremony (recorded live on March 5 for later streaming)?

The Comeback: Season 3 (HBO Max, March 22). Another returning gem is this inventive “mockumentary” style sitcom-about-a-sitcom, starring Lisa Kudrow as a “B-list” television star trying to revive her own faltering career. Slow to catch on in its first season (which originally aired in 2005), it won acclaim (and new fans) when it was rebooted in 2014 by Kudrow and collaborator/co-creator Michael Patrick King (former executive producer of “Sex in the City,” and now returns after a 12-year hiatus for another installment, which tracks “never-was” has-been Valerie Cherish through yet another attempt to make stardom happen. If you like cynical, sharp-edged satire, especially when it’s aimed at the behind-the-scenes world of show-biz, then you’ve probably already discovered this one – but if you haven’t, now’s your chance to jump on board.

Heartbreak High: Season 3 (Netflix, March 25). Fans of this imported Australian teen “dramedy” series – itself the “soft reboot” of another popular Australian series from the ‘90s – will be thrilled for the arrival of its third and final installment, which picks up where it left off in the lives (and sex lives) of the students and teachers of a suburban high school. As always, it can be expected to push the envelope (and some buttons) with its irreverent treatment of issues of class, race, and sexuality – and to deliver another season’s worth of the colorful and striking costume designs that have been acclaimed as a highlight of the show. And yes, it includes a refreshingly significant number of variously queer characters, so if you’re not already on board with his hidden gem of a streamer, we suggest you should give it a shot – you can probably even catch up on the first two seasons before this one drops.

Pretty Lethal (Prime Video, March 25). Fresh from a March 13 debut at the SXSW Film and TV Festival, this girl-power fueled action thriller from director Vicky Jewson and writer Kate Freund centers on a troupe of ballerinas who, while en route to a prestigious ballet competition, are stranded by a bus breakdown and must take shelter at a remote roadside inn run by Uma Thurman as a ruthless crime boss. Needless to say, the girls are forced to adapt their dance prowess into combat skills before the night is over. With a cast that includes Maddie Ziegler, Lana Condor, Avantika, Millicent Simonds, and Michael Culkin, our bet is that it’s sure to be campy fun with a feminist twist.

Forbidden Fruits (Theaters, March 27). Adapted from the play “Of the woman came the beginning of sin, and through her we all die” by Lily Houghton (who co-wrote the screenplay with director Meredith Alloway), this comedy/horror film about a group of young witches who operate a “femme cult” out of the basement of a mall store called “Free Eden” looks like another campy treat, full of witchy wiles and bitchy rivalries, but something about its theatrical pedigree tells us it will also be more than that. Even if we’re wrong, though, we’ll be perfectly happy; why would anyone say no to a delicious piece of camp, especially when it has a cast led by Lili Reinhart, Lola Tung, Victoria Pedretti, and Alexandra Shipp, with creator/influencer Emma Chamberlain in her film debut and heavyweight talent Gabrielle Union thrown in for good measure? We’re ready to join the coven.

Club Cumming (WOW Presents Plus, March 30). Queer icon Alan Cumming (currently riding high as host of “The Traitors”) takes us inside his NYC East Village gay bar, nightclub, and showplace for a behind-the-scenes reality series that spotlights the talent, fashion, and fabulously queer vibe that makes the establishment one of queer New York’s most iconic nightspots. Cabaret singer Daphne Always, go-go dancer and drag performer Michelle Wynters, Drag queen Brini Maxwell, Drag king Cunning Stunt, and Comedian Jake Cornell are among the many reasons why this little slice of the queer New York scene is reason enough alone to become a subscriber to World of Wonder’s streaming platform – though if you’re a “Drag Race” superfan, chances are good you already are.

The Boys: Season 5 (Prime Video, April 8). Amazon’s violent superhero satire, complete with its divisive and deliciously challenging emphasis on queer storylines and its in-your-face caricature of contemporary American “culture war” politics, returns for its fifth and final season, along with all the thorny issues of racism, nationalism, and xenophobia it has showcased all along, and an ensemble cast that includes Karl Urban, Jack Quaid, Antony Starr, Erin Moriarty, and the rest of the usual players. A decidedly queer-informed game-changer in the mainstream fan culture, it’s a show that will be sorely missed – but with several spin-offs already in existence (including the even-queerer “Gen V”) and another (“Vought Rising”) on the way, we can take comfort in knowing that its influence will live on.

Euphoria: Season 3 (HBO Max, April 12). The controversial Sam Levinson-created drama that is HBO’s fourth most-watched series of all time is back after a lengthy hiatus, rejoining the lives of its dysfunctional characters – queer struggling addict Rue (Zendaya), trans teen Jules (Hunter Schafer), abusive sexually insecure football star Nate (Jacob Elordi), and the rest – a full five years later, away from the social traumas of high school and settled into what we can only assume is an equally-dysfunctional life as young adults. Renowned for its cinematic visual styling and its no-holds-barred treatment of “triggering” subject matter, this long-awaited return is likely to be at or near the top of a lot of watchlists – and ours is no exception.

Mother Mary (Theaters, April 17). One of the most promising (and queerest) offerings of the season is this psychological thriller set in the world of pop music, helmed by acclaimed filmmaker David Lowery (“A Ghost Story,” “The Green Knight”) and starring Anne Hathaway (“The Devil Wears Prada,” “Les Misérables”) as a pop singer who becomes entwined in a twisted affair with fashion designer Michaela Cole (“I May Destroy You,” “Black Earth Rising”). Besides its two queer-fan-fave stars, it features trans actress Hunter Schafer (“Euphoria”), FKA Twigs, and Jessica Brown Findlay (“Downton Abbey”) in supporting roles, and to top it all off, it includes a soundtrack full of original songs. With a celebrated director behind it and an award-winning pair of leading ladies, this one has all the potential of a future classic.

The Devil Wears Prada 2 (Theaters, May 1). Meryl Streep is back as Miranda Priestley, need we say more? We know the answer to that is “no,” but we still need to remind you that Anne Hathaway, Emily Blunt, and Stanley Tucci are all part of the deal, too, as this hotly anticipated sequel hits the screen just ahead of the summer rush. Along for the ride are Kenneth Branagh, Justin Theroux, Lucy Liu, B.J. Novak, Conrad Ricamora, Sydney Sweeney, Rachel Bloom, Donatella Versace, and Lady Gaga herself. We trust that will be sufficient to ensure that you will show up on opening day – dressed accordingly, of course.

The Sheep Detectives (Theaters, May 8) Rounding out our roundup with a fun-for-the-family treat that blends live action with animation for an inter-species “whodunnit” with an all-star array of talent, this adaptation of Leonie Swann’s 2005 novel “Three Bags Full” centers on a flock of sheep as they attempt to solve the murder of their beloved shepherd. Boasting onscreen performances from Hugh Jackman, Emma Thompson, Nicholas Braun, Nicholas Galitzine, and Molly Gordon, along with character voices provided by Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Bryan Cranston, Chris O’Dowd, Regina Hall, Patrick Stewart, Bella Ramsey, Brett Goldstein, and Rhys Darby, this one might be just the kind of lightweight entertainment we all need as we move deeper into the confounding year of 2026.

And if not, stay hopeful – the films and shows of summer will be here soon enough.

-

Health4 days ago

Health4 days agoToo afraid to leave home: ICE’s toll on Latino HIV care

-

Movies5 days ago

Movies5 days agoIntense doc offers transcendent treatment of queer fetish pioneer

-

Colombia4 days ago

Colombia4 days agoClaudia López wins primary in Colombian presidential race

-

The White House3 days ago

The White House3 days agoTrump will refuse to sign voting bill without anti-trans provisions