National

Locked up in the Land of Liberty: Part IV

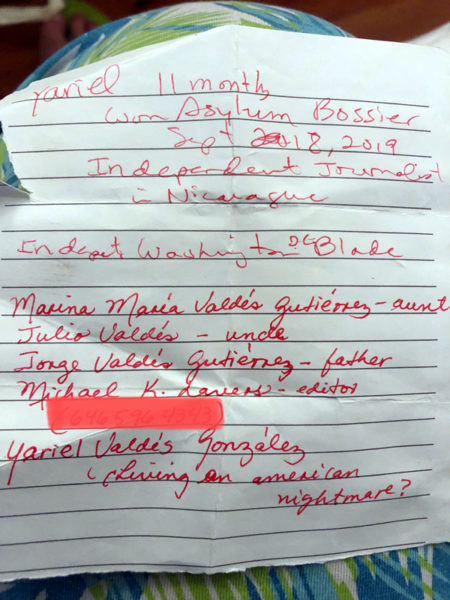

Yariel Valdés González remained in ICE custody until March 4, 2020

Editor’s note: Washington Blade contributor Yariel Valdés González fled his native Cuba to escape persecution because of his work as an independent journalist. He asked for asylum in the U.S. on March 27, 2019. He spent nearly a year in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody until his release on March 4, 2020.

Valdés has written about his experiences in ICE custody that the Blade has published in four parts. The Blade has already published parts I, II and III.

Bossier vs. River (Jan. 13, 2020)

Only a few days outside Bossier confirmed my suspicions: I was being held at a military academy. The disciplinary regime and, above all, the treatment of those officers seemed more like training for a “Marine” than rules of an immigration detention center. I think that, together with many other negative aspects, precipitated our release from that prison. Previous inspections should have raised a red flag about Bossier.

My current detention center surpasses the previous one in every way. The food, for example, is much more abundant, better prepared and varied. I almost cried with joy when I saw a large quantity of chicken on my tray. At Bossier they only gave us a few shreds of chicken drowned in a dark peppery sauce.

There is also a thermos with constant soda and a cooler that never runs out. But that’s not the best thing. They gave me sneakers, socks, flip flops, gloves, pants, two blankets, a towel, a pillow, underwear, two sheets and a complete hygiene kit that includes soap, shaving cream, shampoo, toothpaste, brush and deodorant when I arrived.

My comrades here say that I can request a toiletry item whenever I want. I don’t have to go to the small window under the television through which an officer watches us 24 hours a day. What you had to buy at abusive prices at Bossier is totally free here.

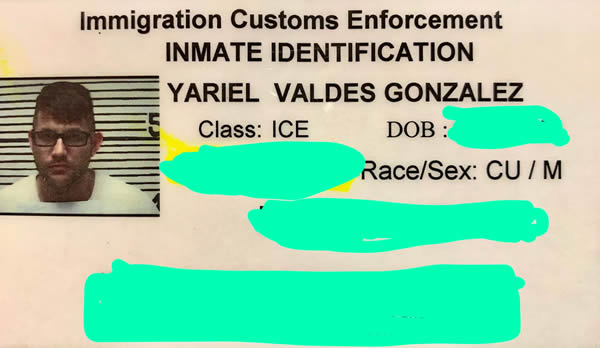

They also provide us razors. To request it, you just have to hand over your ID, and they will not return it to you until you return the blade in perfect condition. The Imperial Regional Detention Facility in Calexico, the first detention center to which I was transferred, had the same rule.

It is wonderful to be able to remove unwanted hair from your face again with the ease of a razor whenever you need it. I was forced to shave with commonly used clippers for months. Laundry service is every day and commissary prices are substantially lower.

But one of these benefits in particular left me totally stunned. We can order pizza and food from restaurants, an unthinkable option in Bossier and one that I had never experienced in previous prisons.

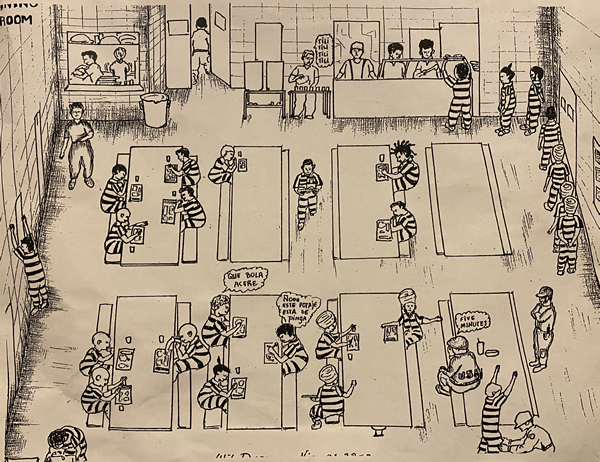

Those who clean the pod are paid $1 a day, as are barbers. Kitchen work is reserved for common prisoners, who reside in pods outside the main building, but within the prison itself.

Living conditions are considerably better, although the pod is much smaller and a bit overcrowded. The cable television has an infinite number of channels, and some of them are even in Spanish. A curtain provides some privacy from the bedroom to shared showers, and a fragrance tablet in the urinals maintains a pleasant smell in that area.

There are three microwaves for heating or cooking food that are available from 5 a.m. until midnight. Telephones and television are available during the same hours. The only thing I miss are the tablets and the screens where I could receive video calls, text messages and photos. River, instead, offers the possibility of having visits from lawyers, family or friends, a right prohibited in Bossier that they were probably violating.

My new comrades tell me access to the yard is one hour almost everyday, unless there is some inconvenience such as bad weather or another issue. It is spacious, with basketball and volleyball courts and a covered seating area.

I went there for the first time yesterday. I jogged for several minutes while listening to radio stations in the area. The radios in River, by the way, are free with a couple of batteries. A tiny radio at Bossier cost $35 and the two batteries were not included. They had to be purchased at a cost of $2.80. Luckily, I still have my radio in good condition. It is a door to the outside world that I can open whenever I want.

The migrant population is made up of Chinese, Cameroonians, Central Americans, Armenians, Nepalese and, of course Cubans. The atmosphere so far is quite calm. I have only made a few friends in the dorm. I was placed in Alpha, the first of the dorms, however, my closest friends were placed in Charlie.

The rest of the immigrants who remained in Bossier upon our departure were also relocated here. I already sent the warden a request to change pods and he came to see me today. He was not very committed to the move, but I still hope that in the next few days it will be possible. My only company so far is loneliness.

This afternoon I joined an exercise group in a corner of the pod in the hope that I would make some new friends. I sometimes play cards with some Central Americans, but it is not the same here. I miss the bullshitting nonsense too much and the level of empathy we had built.

There is also the possibility of a new transfer. Older residents say that immigrants whose cases have been appealed are quickly sent to another detention center because this place is reserved for those who are still attending court hearings.

Many of the judges who handled the cases at Bossier have jurisdiction here as well; including the dreaded Crooks, Brent Landis, Cole (the judge who granted me asylum) and a magistrate named Angela Manson. River is Bossier’s twin for immigration processes with a low rate of asylum attained and bail granted. Parole is still denied. What does make a huge difference is the treatment of the officers. Civilians, not policemen, guard us. There is an atmosphere of respect, kindness and even humor. The officers, men and women, joke and laugh with us as if we were their friends.

Parole: Truth or myth? (Jan. 20, 2020)

This day started with an order that three ICE officers who unexpectedly killed the stillness of the morning slumber at 8 a.m. repeated. They invited us all to get up and listen to the information about parole they brought.

They gave us a notice about parole requests. They made us sign and place our right thumbprint on that document. They insisted that we all had to sign it, even those of us who were not entitled to it. They needed proof that they had informed us of the latest news concerning parole, a right they themselves had crushed.

“On Sept. 5, 2019, a federal district court ruled that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) through its Regional Office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement of New Orleans (NOLA-ICE) must ensure that all persons who are subject to that directive and who have been denied parole prior to Sept. 5, 2019, and are applying for parole are processed from according to various procedures,” the document reads.

We had already seen the same document in Bossier a few weeks before, but the situation had not changed. We viewed the announcement at the time as an institutionalized mockery of us.

The paper said we had a right to parole that a federal court had upheld, but ICE refused to release anyone under that directive. This could be another diversionary strategy to make us believe that they are following the federal court’s orders. Over the last few days, however, I have heard that several immigrants here in Louisiana have been released on parole.

The lawsuit the Southern Poverty Law Center filed against ICE is apparently bearing some fruit. According to the information, the immigrants who have been released are in the appeals process, like me. I want to be positive about this news and I hope it doesn’t fade away, like so many others that have come to raise our spirits for a few hours.

I am right now trying to contact my attorney to submit a request for redetermination of my parole, denied a few days after my “credible fear” interview in Tallahatchie last April. I have letters of support from my family in this country, from my colleagues at the Blade and from other people and institutions who will support me and ensure my well-being if I manage to get out of this confinement.

Victory in my asylum appeal is the other way for my release. Today marks two months since the transcript of my final hearing was sent. I have waited 60 days for a decision from the Virginia court (the Board of Immigration Appeals), which generally takes that long or less to send a decision.

A friend a few days ago told me the answer is positive when an order takes longer than usual to be issued. I honestly don’t know what to believe, but the tension builds in my mind every day as I try to survive pessimism. I check the phone information system every afternoon in desperate search for a phrase that would once again bring me comfort, but nothing.

“Pending,” says the metallic voice through the earpiece and my heart sinks.

An ICE officer with whom I discussed my case a few days ago gave me the same answer yesterday.

“What has your lawyer done for you?” the officer with Asian features asked me.

I replied that I have no right to bail, that parole was closed in this state and I could only wait for the appeals court’s decision.

The officer suggested that my attorney should request a determination of my parole, now that new winds are blowing. The truth is that parole is presented to me with more signs of myth than reality. I no longer know if I am living in a fantasy world or in the real world.

Hugs between brothers (Feb. 1, 2020)

Michael came to see me as soon as he found out that he could visit me in my new “home.” Bossier, my previous detention center, blocked all physical contact with family and friends during the seven months I was there. It only allowed legal visits. They told us that we had video calls when we asked about the reason for the ban. Those were our visits, as if the screen of a tablet could be comparable to physical contact. The video calls did have their advantages, but they could never replace the warm hug of someone who loves you well.

Michael arrived for the afternoon visit between 1-3 p.m. The other visitation hours are between 8-10 a.m., always from Tuesday to Sunday. I did absolutely nothing. The procedure is usually very simple and accessible. They only require an ID from the visitor and that they come on the days and times available.

An officer searched me for anything illegal, including two envelopes with documents, which I intended to give to Michael, as I left the pod. The place for visits is a fairly large room with metal tables and benches, identical to the ones we have inside the pod.

It is decorated with two paintings on the walls: A poorly done lake scene was in front of me and a rather simple reproduction of the Last Supper was to my right. There are two vending machines with candy and soft drinks, which the visitor can buy for the person who they come to see, in one corner.

The room is near one of this prison’s three courtrooms and is also used to enter and leave. Michael was waiting for me at one of the benches. He received me with open arms and his eyes clouded with sadness. I have suffered through this confinement, and he has also experienced it as his own.

We greeted each other with a hug of brothers, because that is what we have become during this time. He is the older brother I never had and our ties are getting stronger every day. The excitement over the meeting exploded in him as he hugged me. I felt his sobs on my shoulder, while at the same time his strength made me feel like we were family again.

“It’s okay, it’s okay,” I told him, and we sat down to talk.

We spoke under the protection of that complicity that has always united us and under the guise an Latina officer. I think she is Puerto Rican. She sat close enough to us to eavesdrop on the conversation. She brought a notebook and wrote observations in it.

This is only the second time we’ve met in person. The first was in Tijuana more than a year ago, when we worked together in Baja California for the Blade. I met him at the pedestrian gate on the Mexican side of the border and this time I received him in a prison on the American side. I never imagined that our friendship would take such a dramatic turn, but what I always knew was that I had added an incredible human being to my life.

He updated me on my family, our mutual friends and mine who have followed every step of my process. He held my hands tightly when my emotions got the better of me. I don’t know how, but I could feel the pounding of his heart.

“I’m here. Everything will be fine. We will win this battle soon,” he said encouragingly.

This meeting also made me smile, even though it brought tears to my eyes. Michael came ready to make me smile with his witty ideas. He told me that he had already made plans with some of his friends in Miami for after my release, including a big celebration. I really need a big party after all of this. I am, however, a realist and I don’t get too excited because disappointments can hurt more. First things first: Get out of ICE custody.

I brought him as a gift a custom-made bracelet made of black and white nylon because he came dressed in a black sweater over a white shirt. I also brought him a small handmade shoe that some comrades make here with bags of goodies. This one was specifically made with Maruchan soup wrappers of various flavors. It came out as a colorful souvenir, which he said will be an ornament on his Christmas tree.

I adore every detail that I gave him, which can never be compared with all the unconditional and selfless help from him. River officials did not allow him to take with him the two envelopes with the manuscripts of these chronicles and other articles. The spy officer was extremely efficient and had already consulted with her supervisor. They luckily allowed him to keep the shoe, the bracelet and a copy of the photo that they took of me when I arrived at this prison. I half-hid it so that my family and friends could see me, although the truth is more scary than pleasant.

We talked about me getting a tattoo in reference to this period in my life. Something so profound to push me to leave a permanent mark on my skin has not happened to me before. I have always believed that tattoos should be inspired by a significant event in someone’s life. It has arrived without a doubt.

I plan to write on my body the phrase “always be free” or something similar with rainbow colors, although my terror of needles still slows me down a bit. Michael, coincidentally, told me that he too wanted to get one with a reference to “freedom.” I learned in a call two days after his visit that he had the word “libertad” or “freedom” in Spanish tattooed on one of his arms in New Orleans.

I never thought he would do it so quickly. That tattoo is yet another proof of how important I am to him. The two-hour visit was too short. Time slipped through my fingers and I very quickly saw myself saying goodbye to my brother as I received him: With a sincere, deep hug and with the hope that it would be the last visit behind bars.

Locked Up with Homophobia (Feb. 10, 2020)

Perhaps the most commonly word in my pod is “faggot,” as crude as it sounds. It was in Bossier and continues to be in the River. The word has no borders. It manages to cross languages, cultures and countries. Everyone, without distinction, learns it and uses it excessively, almost always as a “joke” between comrades.

Homophobia, however, is behind that “harmless” joke. I have personally never felt slighted for being gay in these detention centers, but the comments and conversations I hear on a daily basis are clear evidence of a less than tolerant environment.

When they say “faggot” to someone, it is with the intention of insulting them, as though being gay was the worst thing that could happen to someone. Some in here prefer to be rude, confrontational, vulgar and even a thief than a homosexual. While most say they have nothing against gays, their attitudes sometimes reveal otherwise.

There is even a Honduran in his 30s who pretends to be gay all-day long. He creates, at least for me, a completely offensive character. He uses specific phrases and imitates effeminate behaviors. It is sheer joy for the rest of them, especially when they talk about the “maricavirus,” a prison strain of the coronavirus pandemic that originated in China and is spreading everyday throughout the United States and around the world.

Someone may have been infected with the “maricavirus” if they are not “macho” enough. They say the danger of catching it inside here is high.

One can file a discrimination complaint in situations like this one. These institutions generally act by moving the aggressor to a different pod or they can take other actions, depending on the incident’s magnitude. I have made several friends who have been direct victims of homophobia, the evil from which they have been fleeing in their native countries. They find it ingrained here in some immigrants, especially those who are of Latino descent.

I have also met comrades who pretend to be gay for their asylum cases, and suffer from deep homophobia. They take advantage of the fact that they have arrived in a country where everyone’s rights — and especially where the freedoms and achievements of the LGBTQ community are respected after an intense struggle — are protected.

Just as there are people who despise us, others take advantage of our preference. Some believe that being gay means we are willing to provide “sexual favors” because of the stark isolation into which this confinement forces them. I have luckily never found myself in such a situation, but it happens. I treat everyone with great respect and receive the same from my comrades. I can only let my guard down with a few of them because we have a certain confidence with each other and joke about gay issues. One cannot always be so boring.

I lack a true friend with whom I can speak openly, although I have comrades with whom I have been for many months. I am too careful and I don’t usually expose my life or my feelings so easily.

They placed my gay friends in other pods once we arrived in River. They did not grant my request to live in the same pod with them. Most of them today are no longer in this detention center. They have been transferred as part of their deportation processes, while I feel more and more alone in this fight for my freedom that seems to never end.

A horrible possibility lurks on Monday (Feb. 24, 2020)

Nothing significantly important has happened to me during the approximately 15 days since I last wrote. My appeal remains “pending,” as does my life, frozen in this concrete cage, isolated from everything and everyone. Some things have changed over these days.

ICE granted parole to three people in this pod: A Cameroonian, a Cuban and a Mexican embraced probation to continue their process with their families, a possibility that is forbidden for me because, as my lawyer has explained to me, the cases that are on appeal always don’t qualify to obtain this benefit. It doesn’t matter that I won my case and I don’t have a deportation order.

ICE is simply not interested and will keep me here until I get a response from Virginia. I must definitely adapt to that idea. They are not going to release me when they themselves do not consider that I deserve asylum. It will not happen.

My lawyer during her visit with me on Sunday asked my permission to propose the Southern Poverty Law Center file a lawsuit against ICE because of the injustice they are committing against me and other immigrants.

ICE’s own statutes, according to Lara, state an immigrant who is entitled to asylum must be released immediately, even if the government later requests that the Board of Immigration Appeals review the case. They are violating their own policies, but I am not surprised because they had done it before with parole and they are beginning to see some results after several months of legal battles. I can’t expect a short-term result from that lawsuit and I most likely won’t benefit from it, but it can help prevent future injustices. I will not refuse to cooperate.

I certainly never thought America was like this. The champion of human rights, fighter of injustices throughout the world, closes it’s doors to those confined within its borders, all because of the hatred and xenophobia that Donald Trump’s administration has imposed against us. It is doing everything possible to expel us from here, and nothing to help us.

Another development over the last few days came via a communication with Farook Sha, a Pakistani friend who is in the same situation as me. He learned through a brief exchange of messages that a friendly correctional officer facilitated that the Virginia court denied him asylum. He must once again go before a judge for a new decision in his case. He also let me know it is possible that he is eligible for protection in this country under the U.N. Convention Against Torture or a withholding of deportation, since, as I understood him, he cannot be sent back to his country of origin.

The news obviously shattered him and further deepened the fear of failure. It has now been three months after the delivery of the arguments of my appeal and there is still no decision. This uncertainty is wearing me down every day.

I check the automatic case reporting system in the morning and in the afternoon for some consolation, but the answer remains the same. I will be in detention for 11 months in a few days. It is easy to say, but it has been one of the most terrifying experiences of my life that I do not wish on the worst of my enemies, if I have any.

Lara has prepared me for the worst possible scenario: I lose the appeal and face deportation to Cuba, where the situation is increasingly suffocating for independent journalists. She said we would have to file another appeal at the federal level in that case and we will continue the fight. She must have seen my face of horror because she immediately stopped in her tracks to say, “of course if you are willing to continue.” I didn’t know how to answer her, I still don’t know. I try not to think about that horrible possibility.

Hopelessness and hope for a weekend (Feb. 28, 2020)

The phone system for detained immigrants finally gave a different phrase today. By pressing the appeal box, the respondent informs me that “there is no information about any appeal in your case.” (She previously stated that my appeal was “pending.”) The box on the judge’s decision also says “pending.” (The phone before today indicated that the magistrate had ordered my release.)

That change set off my alarms. It made me think of thousands of possibilities. The Board of Immigration Appeals had already made its ruling, but the phone system did not specify it. The information was extremely ambiguous, yet I began to think about the possibility of my release.

I contacted Michael to find my attorney, the only one who could shed some light on the situation. I received her interpretation a few hours later. Lara said the news was not very promising. That to her meant that the Virginia court agreed with some of the arguments DHS presented in reviewing my case.

The news, through Michael’s muffled voice, completely broke me. All my hopes were shattered and I felt as though darkness took hold of me. I was shattered when I hung up and my mind once again began to betray me, thinking of the worst: A deportation order. My attorney would meet with me tonight to talk more calmly about next steps.

Lara confirmed her suspicions during our visit, but she could not assure anything with absolute certainty because she had not received the board’s letter with the final decision.

“We can’t know anything for sure without that document,” she said, trying to reassure me.

She recommended that I calm down a bit until we see the document, which should arrive early next week.

Even so, I couldn’t hold back my tears after I heard her words. My world was once again reeling and it could perhaps be the final shock that would bring about a tragic ending. But all was not lost and I clung to that hope to overcome the days ahead, although my body could not completely erase that feeling of defeat. My head threatened to explode and at times I felt my heart beating like a wild colt. I lost count of how many painkillers I ingested in my desperation to silence the pounding of my brain, which was constantly agitated.

Despite everything, I received an unexpected visitor on Sunday who managed to cheer me up a bit. An immigrant support group came to rescue me from depression. My lawyer in a previous meeting had asked me to receive them. I honestly didn’t think they were coming so quickly. A woman named Elisabeth Grant-Gibson opened her arms to me, giving me a warm welcome. Feeling that a stranger gives you their affection so spontaneously is something that I did not expect these days, much less in this place.

“I’m not a lawyer, I’m not from ICE, I’m just human,” she said when she introduced herself, a phrase that made me realize how restorative this meeting would be.

I told her about my situation, about my family, about my fears in Cuba and she was shocked by everything through which I have been. She told me about this humanitarian work that she does with many other people in order to bring us a little familiarity and understanding.

The group to which Elisabeth belongs visits detention centers to talk with immigrants, providing them with emotional support and fighting alongside with non-profit organizations that fight to make sure our rights are not trampled on.

I fell apart while talking with Elisabeth, although her visit was an injection of energy and love that I did not expect, but one for which I was crying out. I left that place with a smile on my lips and with a recommendation that she left me at farewell.

“Stay healthy from the body, but especially from here,” she said, pointing to her head, as she saw my despair.

Maybe she doesn’t know how much good she did; making me feel supported, loved and welcomed in this country. She gave me a little confidence in this nation and its people.

Justice delayed … but it comes (March 2, 2020)

A piece of mail with my name on it arrived. You have to leave the pod dressed in the green striped uniform to receive it. An officer outside opened the correspondence in front of me and I could see that it was the envelope with the Board of Immigration Appeals’ decision. My heart rate began to increase. Zero hour arrived. It was the moment of truth.

I hardly understood what I read on the first page, but the word “removed” left me in shock.

“It can’t be, it can’t be,” I told myself and moved on to the rest of the document. The second sheet is more enlightening and contains the verdict, which states the DHS appeal has been dismissed.

“We contribute and affirm the decision of the immigration judge (…) Contrary to the arguments of the DHS appeal, we conclude that the favorable credibility found by the immigration judge that the applicant (that is me) is eligible for asylum as he has established that he has suffered past persecution and has a well-founded fear of persecution.”

It was all I needed to read. My legs began to shake and my heart wanted to jump out of my chest. I asked the officer if I could sit down because I felt that my legs couldn’t hold me for much longer. I reread the document. I could not believe it. It confirmed that DHS had lost the fight in my case and there could no longer be any doubts about my asylum.

The nightmare finally came to an end after a 5-month long appeals process and a total of 11 months in unjust ICE detention. Justice takes time, but it always comes for those who deserve it. I gave my captors 150 more days, but I will not focus my energies on that. I must look forward, although it will of course be impossible to forget everything I have gone through to finally be free.

I will be eternally grateful to this nation for protecting me from the Cuban dictatorship, even if it put me through hell first. Americans are a tough breed to crack. I understand that they must be very careful with those who they allow to cross their borders, but I disagree with their methods.

My old comrades came over to congratulate me once I reached the dorm. I could see sincere joy on their faces and that this news renewed their hope in their particular cases. I began to call my aunt and uncles to give them the good news, the news for which we had waited so long, but they did not answer the phone.

I managed to speak with Michael and I could hear how the emotion overwhelmed him, how the tears of joy barely let him speak and we began to make the plans that we had postponed for so long. He will come to rescue me from this prison and take me to my family in Miami.

I was able to speak with my aunt and uncles a few hours later. It took them a bit to understand, because I had told them the opposite a few days. I felt my voice crack when I managed to understand.

“We won, we won!” I repeated to them and I imagine that everyone exploded with joy on the other end of the line.

I would let my parents know and I recommended they, like Michael, not post anything on social media until he finally saw me breathing freedom on the outside. It has been an exhausting fight, one that has been frustrating at times and one that has inflicted a few emotional wounds that I trust will heal very soon. I still have to get used to the idea that I will have won my asylum twice and that I will soon start my new life.

Epilogue of a victory (March 4, 2020)

I approached three ICE officers visiting the pods after I read to my attorney over the phone the contents of the letter from Virginia and verified that they were not my hallucinations. The officers — two men and a woman — arrived that morning and I showed the document that showed their defeat.

“What do you want me to do with this?” asked the officer, half annoyed after looking at the board’s order.

“I wanted to know when I’m getting out,” I said.

“Do you want to go?” she asked ironically.

“Of course,” I responded quickly

“Well, it seems that you have not read what the paper says in this part below,” she said

I began to get nervous. I sensed another dirty ruse to block my release. The officer said that my case had to go back to court with the judge who granted me asylum. It seemed completely absurd to me, because the Virginia court had agreed with Cole’s ruling and a change of decision was not necessary. But it is apparently the final step of my case, the closing of a long and harrowing process. ICE would prepare all the paperwork for my release with the judge’s order. One of the officers said the process could take a week or more.

I returned indignant and fearful, as is often the case every time I confront them. Those exchanges always leave me in a very bad mood. They returned a few minutes later to take my personal information: Future address, telephone numbers to contact me and to find out how I would get out of detention. I found out that the officers had, once again and this time for my benefit, lied to me.

An officer urgently asked for me while I was taking my last shower in prison. She said they were asking for me because I had a very important call. I thought it was Michael, who was on his way to pick me up, but no. They rushed me out of the pod, for I shouldn’t keep such a distinguished call waiting.

I suddenly found myself sitting in front of the immigration judge, who was in the same room where I had won asylum five months earlier. Lara, my lawyer, was on the phone and the voice in the background belonged to the government prosecutor in my case. It was like deja vu when a cyclical nightmare returns. The judge claimed to have received Virginia’s ruling, which upheld his sentence from months ago. He turned to the government attorney, who claimed not to have been notified of his defeat in the appeals court.

The DHS representative did nothing but stall until the last minute, but His Honor affirmed that everything was ready for my release. He asked if the officers had processed my exit documents and he wished me good luck before ending the hearing. I could perceive a certain feeling of joy in the judge, because his work was impeccable. I thanked him once again and breathed easy as I left the hearing.

Practically all of the belongings that I would take with me were packed when I returned to the pod. I had given things that I would not need to friends, especially those who still had a few months of anguish left. I was scheduled to leave at 2 p.m., and it happened.

Some Cuban and other friends came over to say goodbye when they came for me. It is highly unlikely that our paths will cross again. This time it was me who could see in their faces the joy intertwined with the pain of staying in confinement. They smiled, hugged me and congratulated me … it felt sincere.

It had been raining mercilessly outside from the early hours of the morning. Through the pod’s tiny windows I had seen how the grass could not soak up so much water from the storm, but nothing could darken this day, not even those clouds that turned the afternoon gray and threatened to soak me. I didn’t care!

The check-out process was easy. The officer in charge of my release gave me a laminated ID card with my personal information. The first photo they took of me when I entered this country 11 months ago was on the back. I asked about my passport, but that ID was the only thing ICE would give me with which I could travel. It would have to do! I finally shed that infamous green and white striped jumpsuit and felt human again when I adjusted my pants and long-sleeved shirt.

The clothes literally danced on my body. It was an unmistakable symptom of famine and all kinds of deprivation. I went through a door that I had never even approached and arrived at a small reception area where an officer verified my data. Everything was in order. My phone was dead, I couldn’t tell if it had survived the tragedy. The downpour outside the walls continued unabated, preventing me from running to be free for which I had so often longed.

My only option was to wait for Michael and I had to be patient. He told me during one of our telephone calls to confirm the details of my release that he had fallen in the morning. He was in the hospital with a broken arm, but insisted that nothing would stop him from rescuing me.

I hadn’t been waiting long when I saw him arrive. A giant t-shirt, which made it a bit difficult for him to walk, covered his arm.

We almost collided at the door. The storm outside had blinded him and we hugged tightly for a few seconds when he realized that I was the one who received him. We laughed and got excited. I finally crossed River’s threshold, never to return. We ran through the heavy downpour, which felt like a hurricane, until we reached the car. Michael started the car and I took a giant breath of air that tried to calm me down. I was free once and for all. I still didn’t believe it.

Federal Government

Expert warns Trump’s drastic cuts to HHS will have far-reaching consequences

HRC’s HIV and LGBTQ health policy advocate shared his concerns with the Blade

Ten years ago, as the opioid epidemic ripped through communities across the United States, the recreational use of oxymorphone with contaminated needles led to an explosion of new HIV infections in southern Indiana’s Scott County.

In places like Austin, a city with about 4,000 residents, the rate of diagnoses quickly ballooned to levels seen in some of the hardest-hit nations of sub-Saharan Africa, more than 50 times higher than the national average.

Thankfully, by 2020, NPR reported that the area was rebounding from what was the most devastating drug-fueled HIV epidemic that rural America had ever experienced, with three-quarters of patients managing the disease so well with antiretroviral therapies that their viral loads were undetectable.

Five years after officials called a public health emergency over the outbreak in Scott County, Austin had opened new addiction treatment centers, support groups, and syringe exchanges.

Initially, Indiana’s response was sluggish. The state’s governor at the time, Mike Pence, opposed clean needle exchanges for 29 days before ultimately signing an executive order allowing for a state-supervised program.

The administration in which he would go on to serve as vice president, however, launched an ambitious initiative designed around the objective of ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S. by the end of the decade, using proven public health strategies including syringe exchanges.

NPR further noted “the administration’s HIV goals were championed” by Pence along with Trump’s U.S. Surgeon General, Jerome Adamsthe, who was Indiana’s health commissioner during the outbreak in Austin.

Still, the news service warned, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention determined that 220 U.S. counties were vulnerable to outbreaks of HIV and other blood borne infectious diseases like hepatitis C.

“When you have these outbreaks, they affect other states and counties. It’s a domino effect,” Dr. Rupa Patel, an HIV prevention researcher at Washington University in St. Louis, told NPR. “We have to learn from them. Once you fall behind, you can’t catch up.”

Trump’s approach to public health, including efforts to prevent, detect, mitigate, and treat outbreaks of infectious diseases, looks radically different in his second term.

‘I don’t know why they hate public health so much’

The Washington Blade spoke with Matthew Rose, senior public policy advocate for the Human Rights Campaign, during a recent interview about the the administration’s dramatic cuts and mass layoffs that will totally reshape the way America’s health agencies are run under Trump’s secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

“They’re dismantling all the things around” the first Trump administration’s Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. effort, he said, eliminating key positions and offices within America’s health agencies that support this effort, including by tracking progress toward — or movement away from — the 2030 goalposts.

Rose said there is no evidence to suggest the initiatives combatting HIV that were begun when Trump was in office the first time were ineffective, either in terms of whether their long term cost-savings justified the investment of government resources to administer them or with respect to data showing measurable progress toward ending the epidemic within the decade.

Therefore and in the absence of an alternative explanation,, Rose said he is left with the impression that the Trump-Vance administration does not care about Americans’ public health, especially when it comes to efforts focused on disfavored populations, such as programs supporting access to PrEP to reduce the risk of HIV transmission through sex.

The outbreak in Scott County “can happen over and over again, if we don’t have CDC surveillance,” he warned. “We’re still having a fentanyl crisis in the country that we don’t seem to really want to deal with, but you end up with outbreaks that bloom and bloom very quick and very fast.”

Rose added, “The really crazy thing is that they got rid of disease intervention and branch and response,” referring to the CDC’s National Center for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and Tuberculosis Prevention, specifically its Division of HIV Prevention, and the various branches within that division that are responsible for different aspects of HIV prevention, care, and research. They include HIV Research, Behavioral and Clinical Surveillance, and Detection and Response.

“These are literally the disease detectives that chase down outbreaks,” Rose added. “When there’s a syphilis outbreak in an area, when COVID came along and we had to trace COVID outbreaks, like, those folks are the folks who do this.”

If (or perhaps when) communities experience an outbreak, “We wouldn’t truly know what’s going on until probably 10 years later, when those folks’ CD4 counts finally crash to an AIDS diagnosis level,” he said, at which point “they’re very, very sick.”

“They’ll start looking like we haven’t seen people look since probably 30, 40 years ago,” Rose said, a time well before the advent of highly effective medicines that from the perspective of many patients turned HIV from a death sentence to a manageable disease.

Additionally, “every person that we lose to follow up and care, if they don’t know their status, that’s where the majority of new diagnoses come from,” he said, noting that without the CDC’s work “bringing people back into care,” there is “no way of tracking that.” HIV positive people will continue to potentially transmit the disease to others as “their own health deteriorates at levels that it doesn’t need to deteriorate at,” Rose said, “so, we make it worse.”

Along with the breakthroughs in drug discovery that led to the introduction of highly efficacious and well tolerated antiretrovirals, the use of PrEP by those who are HIV-negative to drastically reduce the risk that they may contract the virus through sex has put the goal of eliminating the epidemic within reach.

“One of the things we learned from things like the PROUD study,” Rose said, referring to randomized placebo-controlled HIV trials conducted in the U.K. in 2016 “ is that if you can get to the highest impacted folks, the most vulnerable folks, for every one person you get on PrEP, you’re getting anywhere from 16 to 23 infections averted.”

Disparities in health outcomes are likely to worsen

Rose noted that “we’re finally starting to stabilize” the disproportionately high rate of new infections among gay and bisexual Black men who have sex with men thanks in large part to the federal government’s work by employees and divisions that were cut by Kennedy’s restructuring of HHS, initiatives like culturally competent public health messaging campaigns for vulnerable populations, addressing subjects like PrEP, other prevention methods, the importance of regular HIV/STI screenings, and the availability of treatments for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

There is no way of knowing if any intervention was effective in the absence of “surveillance units” to monitor the disease’s spread through communities and track mitigation efforts, he said, adding that the gutting of these positions comes as “Latin men have actually been catching [up to] Black men in terms of new diagnoses” while rates among Black and Latina trans women remain high.

Along with NCHHSTP’s Prevention Communication Branch, the health secretary’s near 20 percent cut to CDC staff also eliminated the center’s Division of Behavioral & Clinical Surveillance Branch, its Capacity Development Branch, its Quantitative Sciences Branch, and its HIV Research Branch.

As a result, Rose said “You’re going to see these populations get hit hardest again,” communities that have long suffered disproportionately from the HIV epidemic due to factors like racial or income-based disparities in access to testing and treatment.

Broadly, the CDC is distinguished from other agencies because the Atlanta-based agency’s remit is focused to a significant extent on the population level implementation of public health interventions, endeavoring to change health outcomes, he explained. With respect to PrEP, for example, once the drug was shown safe and effective in clinical research and the evidence supported its use as a critical tool in the federal government’s effort to stop the epidemic, the CDC is responsible for work like making sure at-risk populations who are disinclined to use condoms can stick with (or are sticking with) the medication regimen.

The administration’s cuts encompass programs on the research side as well as the implementation side, Rose said. For example, he pointed to the “decimation” of divisions within the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which conducts studies on HIV interventions from the preclinical basic science stage to double blind clinical trials such as those that led to the introduction of injectable PrEP, which can be administered once every other month after the first two doses.

In fact, Rose said he worked alongside Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, who succeeded Dr. Anthony Fauci as head of NIAID, on the Microbicide Trials Network board looking for behaviorally congruent HIV prevention products for populations that might not wish to take an oral or injectable formulation of PrEP. He added that she is a “brilliant scientist” who helped him better understand the vaginal microbiome as well as the ways in which “we fall short on women’s health and women’s sexual health, and what that means in the context of HIV prevention.”

Together with other top officials like Dr. Jonathan (“Jono”) Mermin, who led the NCHHSTP, on or around April 1, Marrazzo was reportedly offered the chance to either be placed on administrative leave or relocate to Indian Health Service outposts in rural American Indian or Native Alaskan communities located in states like Montana, Oklahoma, and Alaska.

Infectious disease related risks and benefits of research extend beyond HIV

Rose stressed the risks presented by the administration’s decision to shutter divisions within NCHHSTP that were responsible for communications, education and behavioral studies around tuberculosis, especially provided how the disease is underdiscussed as a public health issue within U.S, borders — where rates of infection are elevated in certain communities, like unhoused and incarcerated populations, where queer folks are disproportionately represented.

The restructuring of NCHHSTP and NIAID also raises the chances of outbreaks of viral and bacterial infections spread through sex that these public health workers could have prevented or better contained, Rose said.

Instead, “for some reason, someone thought it was a good idea to get rid of labs at the Division of STIs,” at a time when “we’ve had increases in STIs for the last, like, six years,” including rising rates of congenital syphilis, “the one that kills babies” and increased diagnoses of the disease among gay men.

Additionally, Rose noted disparities in health outcomes for people living with hepatitis C are likely to worsen by the cessation of federal government initiatives to slow the spread of the disease — which co-infects one of every four patients with HIV and can be fatal if untreated because the virus can cause cirrhosis, cancer, failure of the liver — because direct acting antivirals that cure 95 percent of all cases are covered by most insurance plans only when the policyholder has already sustained severe liver damage.

Broadly, “the fact that we’re like, getting rid of the labs to test people means that we’re literally choosing to go backwards, stick our heads in the sand, and hope that no one has the ability to want to say anything,” he added.

Even populations who are less susceptible to infection with diseases like HIV stand to benefit from basic and clinical science research into the disease, Rose said.

He pointed to such examples as the drug discovery studies targeting a vaccine for HIV that ultimately led to the identification of combinations of antivirals that were capable of curing most cases of hepatitis C, the inclusion of participants with HIV in clinical trials that led to the introduction of Ebola vaccines, and breakthroughs in the biomedical understanding of aging that were reached through research into why patients with untreated HIV age more rapidly.

“We continuously find new scientific endeavors that are able to help the general population, but also able to help the LGBTQ population,” Rose said, as “the things that happen in the HIV space spill over to other places.”

“From the LGBTQ health perspective, and especially from the research side,” he said, “we have just, in the last decade, started to really think about what interventions those populations need — not just [with respect to] HIV, but [other health issues like] smoking, alcohol and substance use and abuse,” including “crystal meth, which is always the number two drug in most major cities.”

Likewise, as large swaths of America’s public health infrastructure are unraveled under the direction of the president and his health secretary, the dissolution of each position or each division should not be considered in isolation given (1) the interdisciplinary nature of the work in which these individuals and entities are engaged and (2) the administration’s efforts elsewhere to restrict access to healthcare, especially for disfavored populations like trans and gender-diverse communities.

“There’s first the attack on the research pipeline,” Rose said, such as the HIV Vaccine Trials Network’s identification of an urgent or unmet need (behaviorally congruent methods of HIV prevention for women) and its discovery of a new intervention through research and clinical trials (a ring worn inside the vagina that releases an antiretroviral drug to stop the virus from entering the body during sex).

“Then there’s the destruction of key health interventions,” he said. For example, “STI testing is a public health intervention. It keeps people healthy, and we’re able to reduce the amount of STI floating in populations” through regular testing and monitoring of new diagnoses. “Getting rid of programs that look at and support these [efforts] is really, really bad,” Rose said.

He noted that the administration has endeavored to restrict healthcare access along a variety of fronts, especially when it comes to transgender medicine for youth, Rose said, from working to pass regulations circumscribing the scope of the ACA’s coverage mandate to gutting the HHS Office of Civil Rights such that vulnerable populations have less recourse when they are denied access to care or experience unlawful discrimination in healthcare settings, and conditioning the government’s federal funding for providers and hospital systems on their agreement not to administer guideline directed, evidence based interventions for the treatment of gender dysphoria in youth.

“Last year, CDC documented that we had reduced new HIV infections by 6% and by 23% and 26% in counties that were in the Ending the Epidemic jurisdictions,” Rose said.

In the face of these challenges shortly into the president’s second term, he said, “we will stand up to a scientific rigorous process every time, because we’ve done it every time, and every time we’ve done it, the world has been better for it.”

National

National resources for trans and gender diverse communities

Amid attacks, help is available from wide range of organizations

The Trump administration has launched a series of executive orders and other initiatives restricting the rights of the transgender community since taking power in January, targeting military service, affirming healthcare, and participation in sports.

Though many executive orders are being challenged in court, it’s an uncertain time for a community that feels threatened. Despite the uncertainty, there are resources out there to help.

From legal assistance to mental health support, here’s a list of nonprofits and organizations dedicated to improving the everyday livelihood of trans and gender diverse people. These are mostly national organizations; there are many additional groups that work in local communities across the country. Some of these national groups will connect those in need of help to a local organization.

LEGAL HELP

President Trump issued an executive order declaring there are only two genders –– male and female –– which applies to legal documents and passports. The order doesn’t recognize the idea that one can transition their gender at birth to another gender.

Ash Lazarus Orr filed to renew his passport with a gender marker reflecting his identity. That was in January, and he still hasn’t received it. He refused to accept a passport without an accurate identification of who he is, so he filed a lawsuit with the ACLU in what is now known as Orr v. Trump.

Orr told the Washington Blade that not receiving his passport back has taken away his freedom of visiting family in Canada and receiving gender-affirming care from a trusted provider in Ireland.

The one thing getting him through this uncertain time is knowing who he’s fighting for –– the trans community, his loved ones, and himself.

“I’m trying to be that person that those younger parts of me needed growing up,” Orr said. Check out a couple of legal support organizations below:

Transgender Law Center

The Transgender Law Center (TLC) provides legal resources and assistance. TLC has a list –– called the Attorney Solidarity Network –– of attorneys that can provide advice or representation for trans people.

The organization also has a legal information help desk that answers questions regarding laws or policies impacting trans people.

Website: transgenderlawcenter.org

Phone: 510-587-9696

Email: [email protected]

Advocates For Trans Equality

With a variety of different programs tailored toward legal assistance and advocacy work, Advocates For Trans Equality’s reach is wide.

The non-profit offers the Name Change Project, which provides pro bono legal name change services to low-income trans, gender-non-conforming and nonbinary people by utilizing its partnerships with law firms and corporate law departments.

Advocates For Trans Equality also has departments and programs dedicated to increasing voter engagement, educating lawmakers on trans issues and offering litigation assistance to a small number of cases.

Website: transequality.org

Phone: 202-642-4542

General email: [email protected]

To contact a specific department or program, visit its website above.

ADVOCACY

Looking to take action and get involved? Act now.

American Civil Liberties Union

The ACLU is a national nonprofit organization that mobilizes local communities and advocates for national causes.

Getting involved is as easy as filling out letters to representatives or signing petitions. One live petition is to “defend trans freedom.”

You can also join its People Power platform, where you serve as a volunteer in your community to “advance civil liberties and civil rights for all.” ACLU has different chapters across the country, so visit its website for more information.

Website: aclu.org

Phone: 212-549-2500

MILITARY AND VETERANS

Trump signed an executive order in January banning transgender service members from serving, stating their identity “conflicts with a soldier’s commitment to an honorable, truthful and disciplined lifestyle, even in one’s personal life.”

Though the order has been legally challenged and struck down by a judge, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Rae Timberlake said it’s created an uncertain atmosphere for themself and other troops.

“All of the transgender service members I know have served with honor and integrity for many years…[and we’re] targeted for removal and not subject to any kind of review based on merit,” Timberlake, who joined the Navy at age 17, said. “There’s kind of just this cloud looming over our organizations and our units, because we know any day our transgender shipmates could no longer be on the team.”

But Timberlake’s message to any service member struggling because of the executive order was one of compassion and truth: “There’s no policy that can take away what you’ve accomplished and what you’ve done.”

Here are some organizations that support service members and veterans:

SPARTA Pride

SPARTA is a peer-support group composed of active duty, veteran and “future warrior” service members.

The group also engages in advocacy work and has helped change policies on gender neutral uniforms and reducing the time a trans service member would have to wait to return to their duties during their transition.

Contact SPARTA to learn more about joining its support network.

Website: spartapride.org

Email: [email protected]

Modern Military Association

Modern Military supports service members and veterans through advocacy, legal assistance and mental health support.

It tracks LGBTQ+ and HIV discrimination through reports made on its website, and offers guidance and advice to whoever submitted the report.

It also supports the mental health of LGBTQ+ veterans and their families through its Resilient Heroes Program. By signing up, you’ll receive virtual peer support and case management services with a mental health coordinator.

Website: modernmilitary.org

Phone: 202-328-3244

Email: [email protected]

CRISIS & MENTAL HEALTH SUPPORT

If you have a more urgent matter, or just need someone to listen, here are some organizations you can reach out to:

The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project offers 24/7 counseling services. Calling, texting or chatting is free and confidential, and you’ll get to speak with someone specialized in supporting LGBTQ youth.

The organization also focuses on public education by hosting online LGBTQ suicide prevention trainings. It advocates for policies and laws that contribute to supporting queer youth.

Website: thetrevorproject.org

Crisis hotline: 1-866-488-7386

General inquiry phone number: 212-695-8650

Trans Lifeline

Trans Lifeline is a hotline run and operated by trans people. Whether you’re questioning if you’re trans or are a trans person just wanting to talk, someone will be there to help. It’s free and confidential, and there won’t be any non-consensual active rescue, such as calling the emergency services.

The line is not 24/7, however. Check out its website for hours within your time zone.

Website: translifeline.org

Phone: 877-565-8860

Here are other organizations that offer support to the trans community:

TransFamilies (support): Support for families with a gender diverse child.

TransLatina Coalition (advocacy): Advocates for the specific needs of the transgender, gender expansive and intersex communities in the U.S.

TransAthlete (information): Provides informative resources about trans athletes.

Campaign for Southern Equality’s Trans Youth Emergency Project (healthcare support): A fund to help trans youth access lifesaving healthcare.

TransTech Social (economic empowerment): Dedicated to discovering and empowering the career-ready skills of LGBTQ+ people.

World Professional Association For Transgender Health (health): Resources, symposiums and research dedicated to improving transgender health.

Sylvia Rivera Law Project (legal): Legal programs and services for marginalized communities.

Gender Spectrum (support): Resources and support groups for trans youth and families.

The Okra Project (support): Creates and supports initiatives that provide resources for the Black Trans community.

The White House

White House does not ‘respond’ to reporters’ requests with pronouns included

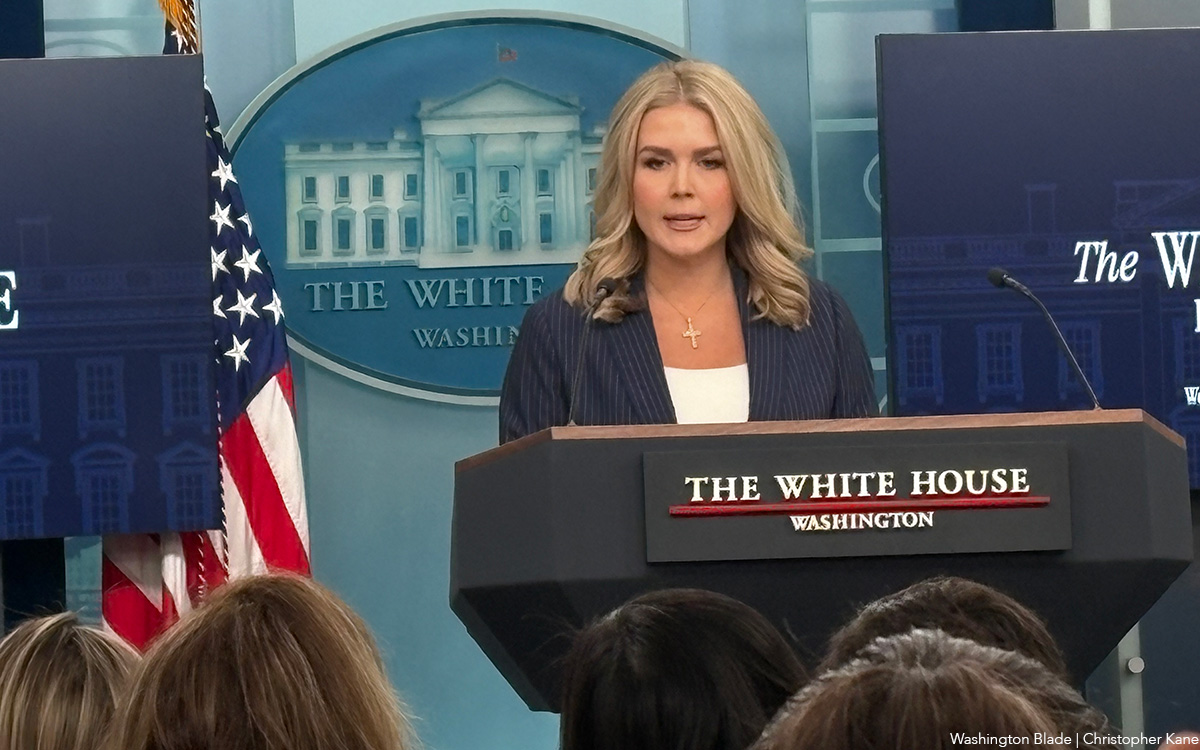

Government workers were ordered not to self-identify their gender in emails

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt and a senior advisor in the Department of Government Efficiency rejected requests from reporters who included their pronouns in the signature box of their emails, each telling different reporters at the New York Times that “as a matter of policy,” the Trump-Vance administration will decline to engage with members of the press on these grounds.

News of the correspondence between the journalists and the two senior officials was reported Tuesday by the Times, which also specified that when reached for comment, the White House declined to “directly say if their responses to the journalists represented a new formal policy of the White House press office, or when the practice had started.”

“Any reporter who chooses to put their preferred pronouns in their bio clearly does not care about biological reality or truth and therefore cannot be trusted to write an honest story,” Leavitt told the Times.

Department of Government Efficiency Senior Advisor Katie Miller responded, “I don’t respond to people who use pronouns in their signatures as it shows they ignore scientific realities and therefore ignore facts.”

Steven Cheung, the White House communications director, wrote in an email to the paper: “If The New York Times spent the same amount of time actually reporting the truth as they do being obsessed with pronouns, maybe they would be a half-decent publication.”

A reporter from Crooked media who got an email similar to those received by the Times reporters said, “I find it baffling that they care more about pronouns than giving journalists accurate information, but here we are.”

The practice of adding pronouns to asocial media bios or the signature box of outgoing emails has been a major sticking point for President Donald Trump’s second administration since Inauguration Day.

On day one, the White House issued an executive order stipulating that the federal government recognizes gender as a binary that is immutably linked to one’s birth sex, a definition excludes the existence of intersex and transgender individuals, notwithstanding the biological realities that natal sex characteristics do not always cleave neatly into male or female, nor do they always align with one’s gender identity .

On these grounds, the president issued another order that included a directive to the entire federal government workforce through the Office of Personnel Management: No pronouns in their emails.

As it became more commonplace in recent years to see emails with “she/her” or “he/him” next to the sender’s name, title, and organization, conservatives politicians and media figures often decried the trend as an effort to shoehorn woke ideas about gender (ideas they believe to be unscientific), or a workplace accommodation made only for the benefit of transgender people, or virtue-signaling on behalf of the LGBTQ left.

There are, however, any number of alternative explanations for why the practice caught on. For example, a cisgender woman may have a gender neutral name like Jordan and want to include “she/her” to avoid confusion.

A spokesman for the Times said: “Evading tough questions certainly runs counter to transparent engagement with free and independent press reporting. But refusing to answer a straightforward request to explain the administration’s policies because of the formatting of an email signature is both a concerning and baffling choice, especially from the highest press office in the U.S. government.”

-

The White House5 days ago

The White House5 days agoWhite House does not ‘respond’ to reporters’ requests with pronouns included

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoReenactment of 1965 gay rights protest at White House set for April 17

-

Hungary2 days ago

Hungary2 days agoHungarian MPs amend constitution to ban public LGBTQ events

-

Maryland2 days ago

Maryland2 days agoFreeState Justice: Transgender activist ‘hijacked’ Moore’s Transgender Day of Visibility event