Books

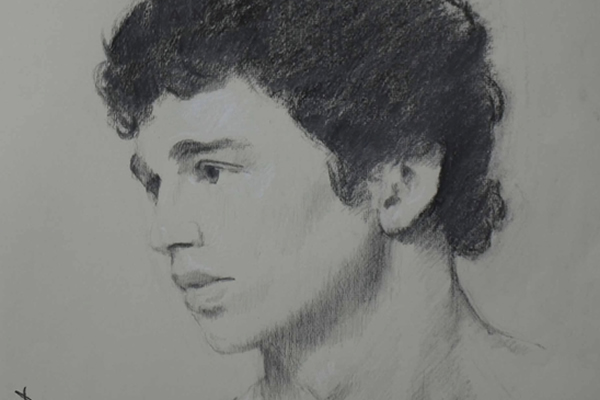

A worthy sequel to ‘Maurice’ revisits classic love story

After going to war, couple reunite in intriguing ‘Alec’

‘Alec’

By William di Canzio

c.2021, Farrar, Straus & Giroux

$27/336 pages

A sequel that’s nearly as good as the original! An intriguing queer love story! What more could you ask for as summer ends?

Today, on and off the page, queers fall in love, have sex, couple up, marry – embrace polyamory – as frequently and openly as politicos trade insults.

But, until recently, you rarely found LGBTQ+ characters in books. With few exceptions, when you encountered queer people in fiction, they were sick, dying, or in jail.

It’s hard to overstate how revolutionary it was for queers when “Maurice” by the queer, British writer E.M. Forster was posthumously published in 1971.

For many of us, it was the first time we read a love story in which queer lovers ended up alive – unrepentant and unpunished.

Forster, who died at 91 in 1970, began writing “Maurice” in 1913 and finished it in 1914. Yet, he felt it couldn’t be published during his lifetime.

Forster’s novels (especially, “A Passage to India” and “Howards End”) were critically acclaimed.

Forster lectured in England and the United States. Listeners heard him on the radio as he read his acclaimed 1939 essay “What I Believe.”

In this essay, Forster spoke of his belief in personal relations, endorsed the humanistic values of “tolerance, good temper and sympathy” and decried authoritarianism.

His assertion in “What I Believe, that “if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend I hope I should have the guts to betray my country,” has been a credo for many.

Yet, because being queer was illegal in the United Kingdom for most of his lifetime, Forster didn’t want to publish “Maurice” while he was alive.

Homosexuality wasn’t decriminalized in the United Kingdom until 1967.

Though he was out to some of his friends, Forster couldn’t be openly gay because of the homophobia of his time.

“Maurice,” which Forster dedicated “To a Happier Year,” doesn’t just have LGBTQ characters. Its two gay male lovers, Cambridge-educated, upper-class Maurice, and Alec, a gamekeeper, end up happily.

We may worry about what obstacles they’ll run into while living in such a repressive time. But we know that they’ve gone off together.

“A happy ending was imperative,” Forster writes in a 1960 “Terminal Note” on “Maurice,” “I shouldn’t have bothered to write otherwise.”

“I was determined that in fiction anyway,” he adds, “two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows, and in this sense Maurice and Alec still roam the greenwood.”

Forster’s legacy has had a reemergence in this century. “On Beauty,” the 2005 novel by Zadie Smith is an homage to “Howards End.”

Matthew Lopez’s play “The Inheritance,” which ran on Broadway, is, also, in part, an homage to “Howards End.”

Many sequels, no matter how well-intended, aren’t good. This is even more true when classic novels like “Maurice” are involved.

Yet, in “Alec,” distinguished, gay playwright di Canzio has pulled off an engrossing, lively, moving feat of the imagination.

In “Maurice,” we see things from Maurice’s perspective. On a visit to his friend Clive, a country squire, he meets Alec, Clive’s game keeper.

We know that Alec and Maurice, after both trying to blackmail each other, fall in love. But we learn little about Alec except that he loves Maurice.

In “Alec,” we view things from Alec’s eyes. Alec, in di Canzio’s reimagining, is a three-dimensional character with feelings, ambitions and a back story.

Born in Dorset, England in 1893 to working class parents, Alec loves to read. He knows, because of his class, that he won’t be able to go to college.

But he soaks up as much literature as he can at the library.

He enjoys reading about classic Greek myths and looking at pictures of art depicting the hunky, mythic heroes.

Early on, Alec knows that he likes boys and men. Though there’s no way he can be openly gay, he’s fine with his sexuality.

“It kept him out of trouble with girls,” di Canzio writes.

Following his father in his line of work, doesn’t appeal to Alec. His dad is a butcher. He doesn’t want to become a servant to rich people if he’d have to be at their beck and call inside their house. Knowing that he has to do some type of work, Alec becomes a gamekeeper for Clive, a country squire.

He and Maurice meet when Maurice visits Clive. As in “Maurice,” the lovers, after much angst and bungled blackmail attempts, go off together.

Up to this point, di Canzio is following the plot of “Maurice” – even quoting some of the dialogue from the novel.

In lesser hands, this might seem too plodding or too derivative. But di Canzio’s retelling the story, though a bit slow, is fresh. You want to keep reading.

The lovers live together happily for a time. They can’t be openly gay. Yet, they find people like themselves and LGBTQ-friendly folk in salons, clubs, and other underground queer spaces.

World War I shatters their happiness. Serving under horrific conditions in separate places, Alec and Maurice don’t know if they’ll survive or find each other after the war.

“How many of our stories have been expunged – from history, from memory?” a friend asks the couple.

You’ll keep turning the page to discover how Alec and Maurice’s story ends.

Books

How one gay Catholic helped change the world

‘A Prince of a Boy,’ falls short of author’s previous work

Brian McNaught, the pioneering gay activist and author of 1986’s “On Being Gay” and 1993’s “Gay Issues in the Workplace,” has written a personal account about his Catholic faith and homosexuality. It is a memoir without much substance.

“A Prince of a Boy: How One Gay Catholic Helped Change the World” (Cascade Books) is a strong personal statement by McNaught. He helped change family relationships. He helped change attitudes about homosexuality. He helped change workplaces, but the world?

In January 2023, the Catholic News Service reported that Pope Francis announced that, “being homosexual is not a crime.” In December 2023, NPR reported that Pope Francis approved “Catholic blessings for same-sex couples, but not for marriage.” Francis died Monday at age 88. Although Catholics may not see homosexuality as a crime, they see sex outside of marriage as a sin. They see same-sex marriage as a sin.

In 2021, Gallup reported that membership in the Catholic Church had declined 20 percent since 2000. In 2025, the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study found that nearly 40 percent of Americans identified as Protestant, while the same study found that only 19 percent identified as Catholic.

McNaught devotes much of his book to his life as a gay Catholic. It is challenging to read about his personal struggle. Some readers may find it interesting. Others might find it boring. Catholic readers may find it more compelling than Protestant readers.

As the above statistics prove, McNaught has much more work to do to change the Catholic Church’s views about homosexuality. We should be glad for his contribution to the debate within the Catholic Church. We should pray for full acceptance of gays in the Catholic Church.

“A Prince of a Boy” becomes more interesting when McNaught describes his work as an educator on LGBTQ issues. He has had an impact on workplace policies, academic programs, and public education, and his lectures, books, and other materials are widely used.

Based on my experience in the federal government and volunteering with LGBTQ organizations from the Bay Area to Washington, D.C., I believe McNaught’s work as an educator has improved LGBTQ lives, careers, and families. During the Clinton administration, I gave many copies of “Gay Issues in the Workplace” to personnel directors. I felt their staff could benefit from reading it. I thought it would help the lives and careers of my federal LGBTQ colleagues.

McNaught’s “A Prince of a Boy” was released in December 2024. Anti-gay crusader Anita Bryant died the same month. Bryant campaigned against a gay rights law in Florida. She began a national campaign against gays.

When Bryant successfully reversed a gay rights ordinance in Dade County, Florida, McNaught wrote the important essay “Dear Anita, Late Night Thoughts of an Irish Catholic Homosexual.” The essay is not in “A Prince of a Boy”; however, McNaught mentions Bryant.

In his training programs, McNaught describes homosexuals as journeying from confusion to denial to acceptance to pride. “Anita Bryant and AIDS brought Gay people to identity pride very quickly,” McNaught writes. San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk (1930-1978) and other activists reached similar conclusions about Bryant’s vicious anti-gay campaign.

McNaught helped change the LGBTQ world and brought pride to many people’s lives. McNaught walks in pride, works in pride, and educates others in pride.

“A Prince of a Boy” is a disappointing book. It provides small details about Brian McNaught’s large, proud life. A meaningful biography about this great gay leader is long overdue.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

Books

‘Pronoun Trouble’ reminds us that punctuation matters

‘They’ has been a shape-shifter for more than 700 years

‘Pronoun Trouble’

By John McWhorter

c.2025, Avery

$28/240 pages

Punctuation matters.

It’s tempting to skip a period at the end of a sentence Tempting to overuse exclamation points!!! very tempting to MeSs with capital letters. Dont use apostrophes. Ask a question and ignore the proper punctuation commas or question marks because seriously who cares. So guess what? Someone does, punctuation really matters, and as you’ll see in “Pronoun Trouble” by John McWhorter, so do other parts of our language.

Conversation is an odd thing. It’s spontaneous, it ebbs and flows, and it’s often inferred. Take, for instance, if you talk about him. Chances are, everyone in the conversation knows who him is. Or he. That guy there.

That’s the handy part about pronouns. Says McWhorter, pronouns “function as shorthand” for whomever we’re discussing or referring to. They’re “part of our hardwiring,” they’re found in all languages, and they’ve been around for centuries.

And, yes, pronouns are fluid.

For example, there’s the first-person pronoun, I as in me and there we go again. The singular I solely affects what comes afterward. You say “he-she IS,” and “they-you ARE” but I am. From “Black English,” I has also morphed into the perfectly acceptable Ima, shorthand for “I am going to.” Mind blown.

If you love Shakespeare, you may’ve noticed that he uses both thou and you in his plays. The former was once left to commoners and lower classes, while the latter was for people of high status or less formal situations. From you, we get y’all, yeet, ya, you-uns, and yinz. We also get “you guys,” which may have nothing to do with guys.

We and us are warmer in tone because of the inclusion implied. She is often casually used to imply cars, boats, and – warmly or not – gay men, in certain settings. It “lacks personhood,” and to use it in reference to a human is “barbarity.”

And yes, though it can sometimes be confusing to modern speakers, the singular word “they” has been a “shape-shifter” for more than 700 years.

Your high school English teacher would be proud of you, if you pick up “Pronoun Trouble.” Sadly, though, you might need her again to make sense of big parts of this book: What you’ll find here is a delightful romp through language, but it’s also very erudite.

Author John McWhorter invites readers along to conjugate verbs, and doing so will take you back to ancient literature, on a fascinating journey that’s perfect for word nerds and anyone who loves language. You’ll likely find a bit of controversy here or there on various entries, but you’ll also find humor and pop culture, an explanation for why zie never took off, and assurance that the whole flap over strictly-gendered pronouns is nothing but overblown protestation. Readers who have opinions will like that.

Still, if you just want the pronoun you want, a little between-the-lines looking is necessary here, so beware. “Pronoun Trouble” is perfect for linguists, writers, and those who love to play with words but for most readers, it’s a different kind of book, period.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

‘The Cost of Fear’

By Meg Stone

c.2025, Beacon Press

$26.95/232 pages

The footsteps fell behind you, keeping pace.

They were loud as an airplane, a few decibels below the beat of your heart. Yes, someone was following you, and you shouldn’t have let it happen. You’re no dummy. You’re no wimp. Read the new book, “The Cost of Fear” by Meg Stone, and you’re no statistic. Ask around.

Query young women, older women, grandmothers, and teenagers. Ask gay men, lesbians, and trans individuals, and chances are that every one of them has a story of being scared of another person in a public place. Scared – or worse.

Says author Meg Stone, nearly half of the women in a recent survey reported having “experienced… unwanted sexual contact” of some sort. Almost a quarter of the men surveyed said the same. Nearly 30 percent of men in another survey admitted to having “perpetrated some form of sexual assault.”

We focus on these statistics, says Stone, but we advise ineffectual safety measures.

“Victim blame is rampant,” she says, and women and LGBTQ individuals are taught avoidance methods that may not work. If someone’s in the “early stages of their careers,” perpetrators may still hold all the cards through threats and career blackmail. Stone cites cases in which someone who was assaulted reported the crime, but police dropped the ball. Old tropes still exist and repeating or relying on them may be downright dangerous.

As a result of such ineffectiveness, fear keeps frightened individuals from normal activities, leaving the house, shopping, going out with friends for an evening.

So how can you stay safe?

Says Stone, learn how to fight back by using your whole body, not just your hands. Be willing to record what’s happening. Don’t abandon your activism, she says; in fact, join a group that helps give people tools to protect themselves. Learn the right way to stand up for someone who’s uncomfortable or endangered. Remember that you can’t be blamed for another person’s bad behavior, and it shouldn’t mean you can’t react.

If you pick up “The Cost of Fear,” hoping to learn ways to protect yourself, there are two things to keep in mind.

First, though most of this book is written for women, it doesn’t take much of a leap to see how its advice could translate to any other world. Author Stone, in fact, includes people of all ages, genders, and all races in her case studies and lessons, and she clearly explains a bit of what she teaches in her classes. That width is helpful, and welcome.

Secondly, she asks readers to do something potentially controversial: she requests changes in sentencing laws for certain former and rehabilitated abusers, particularly for offenders who were teens when sentenced. Stone lays out her reasoning and begs for understanding; still, some readers may be resistant and some may be triggered.

Keep that in mind, and “The Cost of Fear” is a great book for a young adult or anyone who needs to increase alertness, adopt careful practices, and stay safe. Take steps to have it soon.

The Blade may receive commissions from qualifying purchases made via this post.

-

Federal Government2 days ago

Federal Government2 days agoHHS to retire 988 crisis lifeline for LGBTQ youth

-

Opinions2 days ago

Opinions2 days agoDavid Hogg’s arrogant, self-indulgent stunt

-

District of Columbia2 days ago

District of Columbia2 days agoD.C. police seek help in identifying suspect in anti-gay threats case

-

Opinions2 days ago

Opinions2 days agoOn Pope Francis, Opus Dei and ongoing religious intolerance