Health

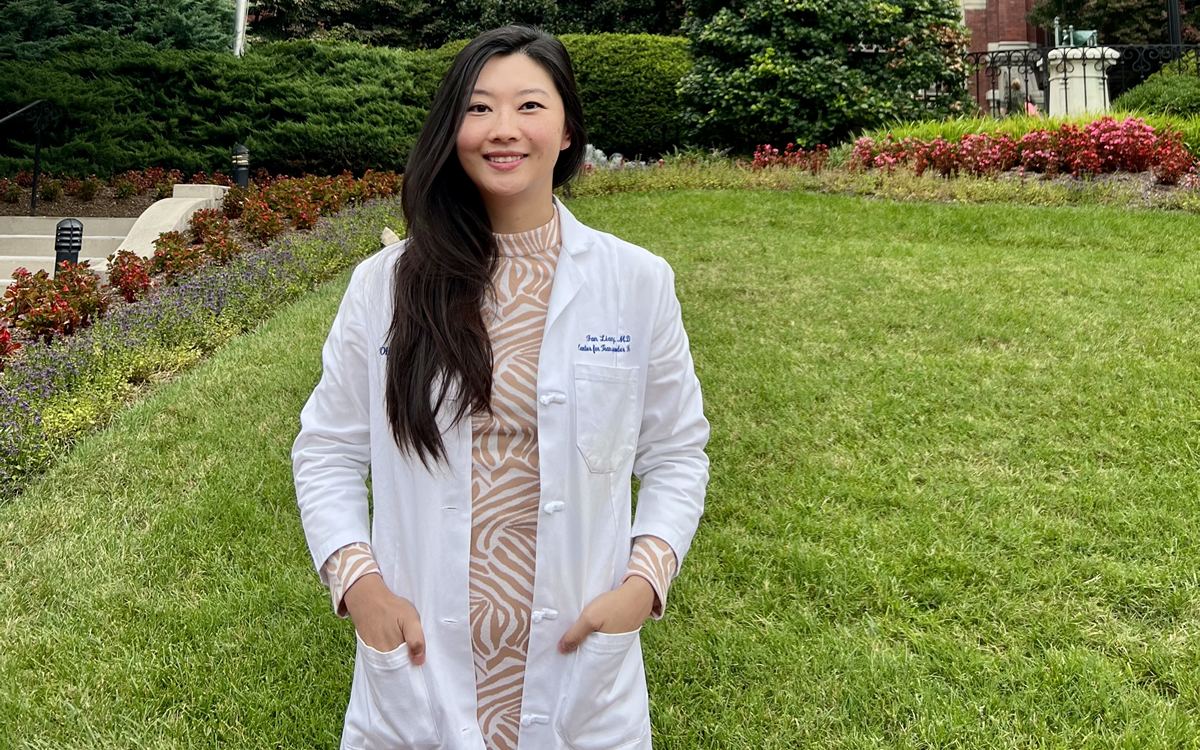

EXCLUSIVE: Meet the director of Johns Hopkins Center for Transgender Health

Dr. Fan Liang on politicizing healthcare, fear among patients

The topic of gender affirming healthcare has never attracted more attention or scrutiny, presenting challenges for both patients and providers, including Dr. Fan Liang, medical director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health and assistant professor of plastic and reconstructive surgery.

Speaking with the Washington Blade by phone last week, Liang shared her perspective on a variety of topics, including her concerns about the ways in which media organizations and others have shaped the discourse about gender affirming care.

Too often, she said, the public is provided incomplete or inaccurate information, framed with politically charged and polarizing language rather than balanced and nuanced reporting for the benefit of audiences who might have little to no familiarity with the topics at hand.

“This is an evolving field that requires input from many different types of specialists,” Liang noted, so one issue comes when providers “start to comment outside of their scope of practice, or extrapolate into everybody’s experience.”

A more intractable and difficult problem, Liang said, is presented by the fact that, “issues with transgender health have really taken center stage with regard to national politics, and as a result of that, the narrative has really been reduced to an unsophisticated representation of what’s going on.”

“I think that is dangerous for patients and for the community that these patients live in and have to work in and survive in because it paints a picture that is really inaccurate,” she said.

Conservative state legislatures across the country have introduced a record number of anti-LGBTQ bills this year, passing dozens, including a slew of anti-trans healthcare restrictions. The Human Rights Campaign reports 35.1 percent of transgender youth now live in states that have passed bans on gender affirming care, many of which carry criminal penalties for providers.

A big part of the Center’s work, Liang told the Blade, involves working closely with trans patients and organizations like Trans Maryland and the Trans Rights Advocacy Coalition “to make sure that the community’s voices are being heard, so that we’re able to represent those interests here.”

She described “a generalized sense of anxiety and fear,” concerns that she said are “pervasive throughout the community,” over “access to surgery and to overall gender healthcare.”

“I get a lot of questions about that,” she said.

While Liang has not yet worked with any patients who traveled to the Center because gender affirming care was banned in the states where they reside, she said, “I do anticipate that will happen in the relatively near future.”

Challenges for clinicians

The political climate “really interferes in physician autonomy and basically using our training and discretion to provide the best therapies that we can,” based on research and evidence-based guidelines from medical organizations on best practices standards of care, Liang said.

“I earnestly believe that people who go into medicine try to do right by their patients and try to provide exceptional care whenever they can,” she said. “When I speak to other providers who are engaged in trans care, the reason they entered the field was because they saw patients that were suffering and had no other providers to go to and they were filling a need that desperately needed to be filled.”

“It is unfortunate that their motives are being misinterpreted, because it is causing significant emotional harm to these providers who are being targeted,” Liang said, noting “there is so much vitriol from the anti-trans side of things,” including “this narrative out there that physicians are providing trans care because of financial reasons or because of some sort of politically motivated, I don’t know, conspiracy.”

The political climate, along with the realities of practicing in this speciality, may threaten to stem the pipeline of new providers whose practice would otherwise include gender affirming care, said Liang, who serves on the interview board for incoming residents who are looking to specialize in plastic surgery.

Many, perhaps even most, she said, are eager to explore transgender care, often because, particularly among young trainees, they are friends with trans and non-binary people. “I don’t know how much of that interest persists as they move through the training pipeline, because — especially if they are at an institution that does provide trans care — they do see a lot of the struggles that physicians encounter in being able to offer these services.”

Liang noted the “significant hurdles from an insurance standpoint” and the “significant prerequisites in order to access surgery,” which require “a tremendous amount of back-end coordination and optimization of the logistics for surgical readiness.”

“And then,” she said, “they see a lot of the backlash in the media against trans providers, and I think that that does discourage residents who otherwise would be interested in the field because physicians, by and large, are a pretty conservative bunch. And having them start their practice where they’re sort of stepping into a political minefield is not ideal.”

Speaking up can be beneficial but risky

“Some physicians feel like they can make the most amount of impact by being advocates for the patient population on a national stage or being more vocal about how anti-trans legislation has been impacting their patients,” Liang said.

“My goal, as the director for the Center for Transgender Health here at Hopkins is really to normalize this care to allow for the open conversation and discussion amongst providers to create a safe space for people to feel comfortable providing this care,” she said.

Destigmatizing gender affirming care and connecting clinicians who practice in this space will help these providers understand they are not “functioning in isolation” and instead are part of “a national effort and a nationally concerted effort toward delivering state-of-the-art health care,” Liang said.

“It’s important,” she said, to “bring the generalized healthcare community to the table in offering these services and have a frank discussion when it comes to education, research and teaching.”

Other providers, however, “do not feel comfortable putting themselves into that place of vulnerability,” Liang said, “and I don’t fault them for it because I personally know people who’ve received death threats and who have been targeted because of what they say to the media,” in many cases because their comments were reported incorrectly or out of context.

In July, Liang participated in an emergency trans rights roundtable on Capitol Hill with representatives from advocacy groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Transgender Law Center, as well as members of Congress including U.S. Reps. Mark Takano (D-Calif.), Barbara Lee (D-Calif.), and Sara Jacobs (D-Calif.).

She told the Blade it was “a really wonderful experience” to “hear the heartfelt stories” of the panelists advocating on behalf of themselves, their friends, and their families, earning the attention of members of Congress.

“I do think advocacy is important,” Liang told the Blade. “I try to make time for it when I can,” she said, “but I have to balance that with all of my other clinical obligations.”

Finding compassion and lowering the temperature

On Aug. 1, The Baltimore Banner reported that the director of the Mayor’s Office of LGBTQ Affairs in Baltimore filed a discrimination complaint with the city’s Office of Equity and Civil Rights against the Hopkins Center for Transgender and Gender Expansive Health. (The story was also published by the Washington Blade, which has a media partnership with the Banner.)

Asked for comment, Liang said “it was an upsetting article to read,” adding, “I was upset that there wasn’t more due diligence done to investigate a little bit further” because instead the article presents “just this one person’s account of things.”

She noted there is “not much I can say from a physician standpoint because everything is contained within HIPAA,” the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which prohibits providers from even acknowledging which patients they may or may not have worked with.

The Banner article underscores the importance of journalists’ obligations to “make sure there is due diligence to confirm sources and make sure things are accurate,” Liang said, including, of course, when covering complicated and politically fraught subjects like gender affirming care.

“On the one hand, it’s really wonderful that there’s a fair amount of press being dedicated to trans issues around the country,” Liang said, but what is “frustrating for me is these conversations always seem to be so loaded and politically charged, and there doesn’t seem to be much space for people to ask earnest and honest questions” without taking heat from either side.

There is “compassion to be offered for patients who are struggling to receive basic health care” as well as for “people who are struggling to understand how this issue is evolving,” those for whom the matter is “uncharted territory” and therefore likely to “cause consternation and fear,” she said.

“Most of the time, the way to overcome” this is to cultivate “relationships with people who do identify as transgender or non-binary” on the grassroots level, she said, while leaving room “for people to ask earnest and honest questions.”

Removing the artificial “us-versus-them” paradigm provides “opportunity for more compassionate interactions,” Liang said.

At the same time, she conceded, amid the heightened polarization and escalation of an anti-trans backlash over the last few years, efforts to fight sensationalization with compassion and understanding have often fallen short, presenting hurdles that have long plagued other areas of science and medicine like abortions and vaccines.

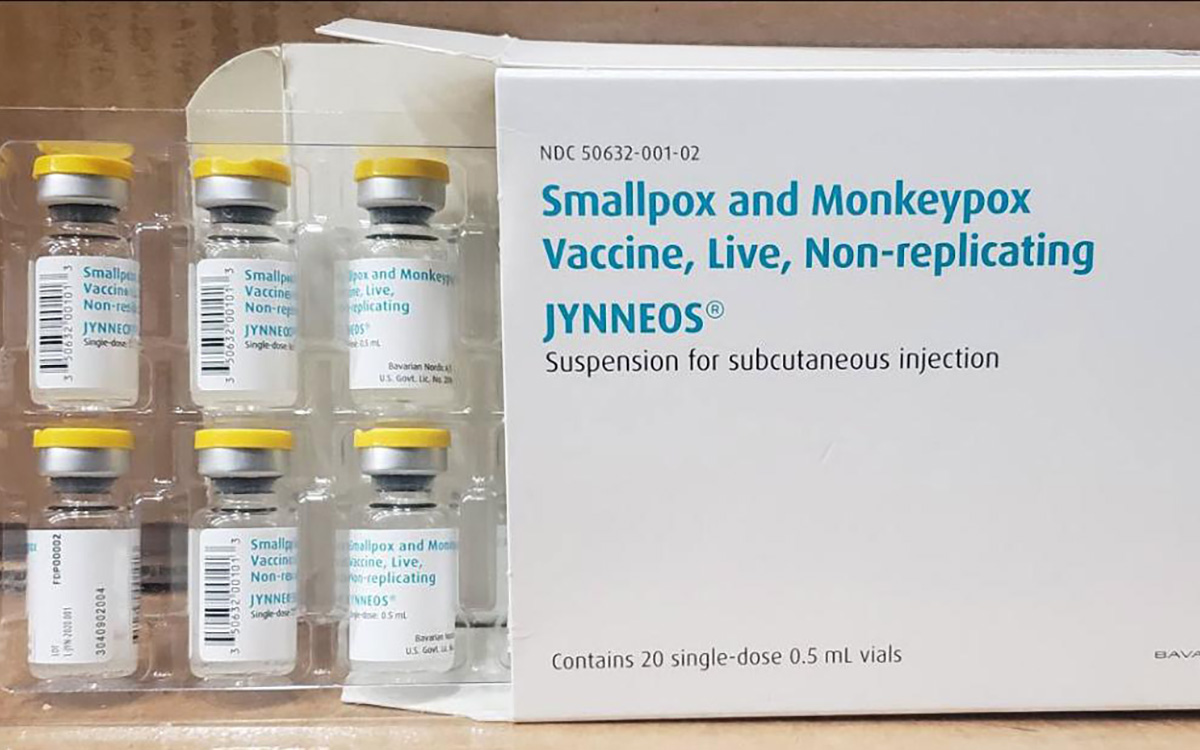

Monkeypox

US contributes more than $90 million to fight mpox outbreak in Africa

WHO and Africa CDC has declared a public health emergency

The U.S. has contributed more than $90 million to the fight against the mpox outbreak in Africa.

The U.S. Agency for International Development on Tuesday in a press release announced “up to an additional” $35 million “in emergency health assistance to bolster response efforts for the clade I mpox outbreak in Central and Eastern Africa, pending congressional notification.” The press release notes the Biden-Harris administration previously pledged more than $55 million to fight the outbreak in Congo and other African countries.

“The additional assistance announced today will enable USAID to continue working closely with affected countries, as well as regional and global health partners, to expand support and reduce the impact of this outbreak as it continues to evolve,” it reads. “USAID support includes assistance with surveillance, diagnostics, risk communication and community engagement, infection prevention and control, case management, and vaccination planning and coordination.”

The World Health Organization and the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last week declared the outbreak a public health emergency.

The Washington Blade last week reported there are more than 17,000 suspected mpox cases across in Congo, Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, and other African countries. The outbreak has claimed more than 500 lives, mostly in Congo.

Health

Mpox outbreak in Africa declared global health emergency

ONE: 10 million vaccine doses needed on the continent

Medical facilities that provide treatment to gay and bisexual men in some East African countries are already collaborating with them to prevent the spread of a new wave of mpox cases after the World Health Organization on Wednesday declared a global health emergency.

The collaboration, both in Uganda and Kenya, comes amid WHO’s latest report released on Aug. 12, which reveals that nine out of every 10 reported mpox cases are men with sex as the most common cause of infection.

The global mpox outbreak report — based on data that national authorities collected between January 2022 and June of this year — notes 87,189 of the 90,410 reported cases were men. Ninety-six percent of whom were infected through sex.

Sexual contact as the leading mode of transmission accounted for 19,102 of 22,802 cases, followed by non-sexual person-to-person contact. Genital rash was the most common symptom, followed by fever and systemic rash.

The WHO report states the pattern of mpox virus transmission has persisted over the last six months, with 97 percent of new cases reporting sexual contact through oral, vaginal, or anal sex with infected people.

“Sexual transmission has been recorded in the Democratic Republic of Congo among sex workers and men who have sex with men,” the report reads. “Among cases exposed through sexual contact in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, some individuals present only with genital lesions, rather than the more typical extensive rash associated with the virus.”

The growing mpox cases, which are now more than 2,800 reported cases in at least 13 African countries that include Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, and prompted the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention this week to declare the disease a public health emergency for resource mobilization on the continent to tackle it.

“Africa has long been on the frontlines in the fight against infectious diseases, often with limited resources,” said Africa CDC Director General Jean Kaseya. “The battle against Mpox demands a global response. We need your support, expertise, and solidarity. The world cannot afford to turn a blind eye to this crisis.”

The disease has so far claimed more than 500 lives, mostly in Congo, even as the Africa CDC notes suspected mpox cases across the continent have surged past 17,000, compared to 7,146 cases in 2022 and 14,957 cases last year.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg when we consider the many weaknesses in surveillance, laboratory testing, and contact tracing,” Kaseya said.

WHO, led by Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, also followed the Africa CDC’s move by declaring the mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern.

The latest WHO report reveals that men, including those who identify as gay and bisexual, constitute most mpox cases in Kenya and Uganda. The two countries have recorded their first cases, and has put queer rights organizations and health care centers that treat the LGBTQ community on high alert.

The Uganda Minority Shelters Consortium, for example, confirmed to the Washington Blade that the collaboration with health service providers to prevent the spread of mpox among gay and bisexual men is “nascent and uneven.”

“While some community-led health service providers such as Ark Wellness Clinic, Children of the Sun Clinic, Ice Breakers Uganda Clinic, and Happy Family Youth Clinic, have demonstrated commendable efforts, widespread collaboration on mpox prevention remains a significant gap,” UMSC Coordinator John Grace stated. “This is particularly evident when compared to the response to the previous Red Eyes outbreak within the LGBT community.”

Grace noted that as of Wednesday, there were no known queer-friendly health service providers to offer mpox vaccinations to men who have sex with men. He called for health care centers to provide inclusive services and a more coordinated approach.

Although Grace pointed out the fear of discrimination — and particularly Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act — remains a big barrier to mpox prevention through testing, vaccination, and treatment among queer people, he confirmed no mpox cases have been reported among the LGBTQ community.

Uganda so far has reported two mpox cases — refugees who had travelled from Congo.

“We are for the most part encouraging safer sex practices even after potential future vaccinations are conducted as it can also be spread through bodily fluids like saliva and sweat,” Grace said.

Grace also noted that raising awareness about mpox among the queer community and seeking treatment when infected remains a challenge due to the historical and ongoing homophobic stigma and that more comprehensive and reliable advocacy is needed. He said Grindr and other digital platforms have been crucial in raising awareness.

The declarations of mpox as a global health emergency have already attracted demand for global leaders to support African countries to swiftly obtain the necessary vaccines and diagnostics.

“History shows we must act quickly and decisively when a public health emergency strikes. The current Mpox outbreak in Africa is one such emergency,” said ONE Global Health Senior Policy Director Jenny Ottenhoff.

ONE is a global, nonpartisan organization that advocates for the investments needed to create economic opportunities and healthier lives in Africa.

Ottenhoff warned failure to support the African countries with medical supplies needed to tackle mpox would leave the continent defenseless against the virus.

To ensure that African countries are adequately supported, ONE wants governments and pharmaceutical companies to urgently increase the provision of mpox vaccines so that the most affected African countries have affordable access to them. It also notes 10 million vaccine doses are currently needed to control the mpox outbreak in Africa, yet the continent has only 200,000 doses.

The Blade has reached out to Ishtar MSM, a community-based healthcare center in Nairobi, Kenya, that offers to service to gay and bisexual men, about their response to the mpox outbreak.

Health

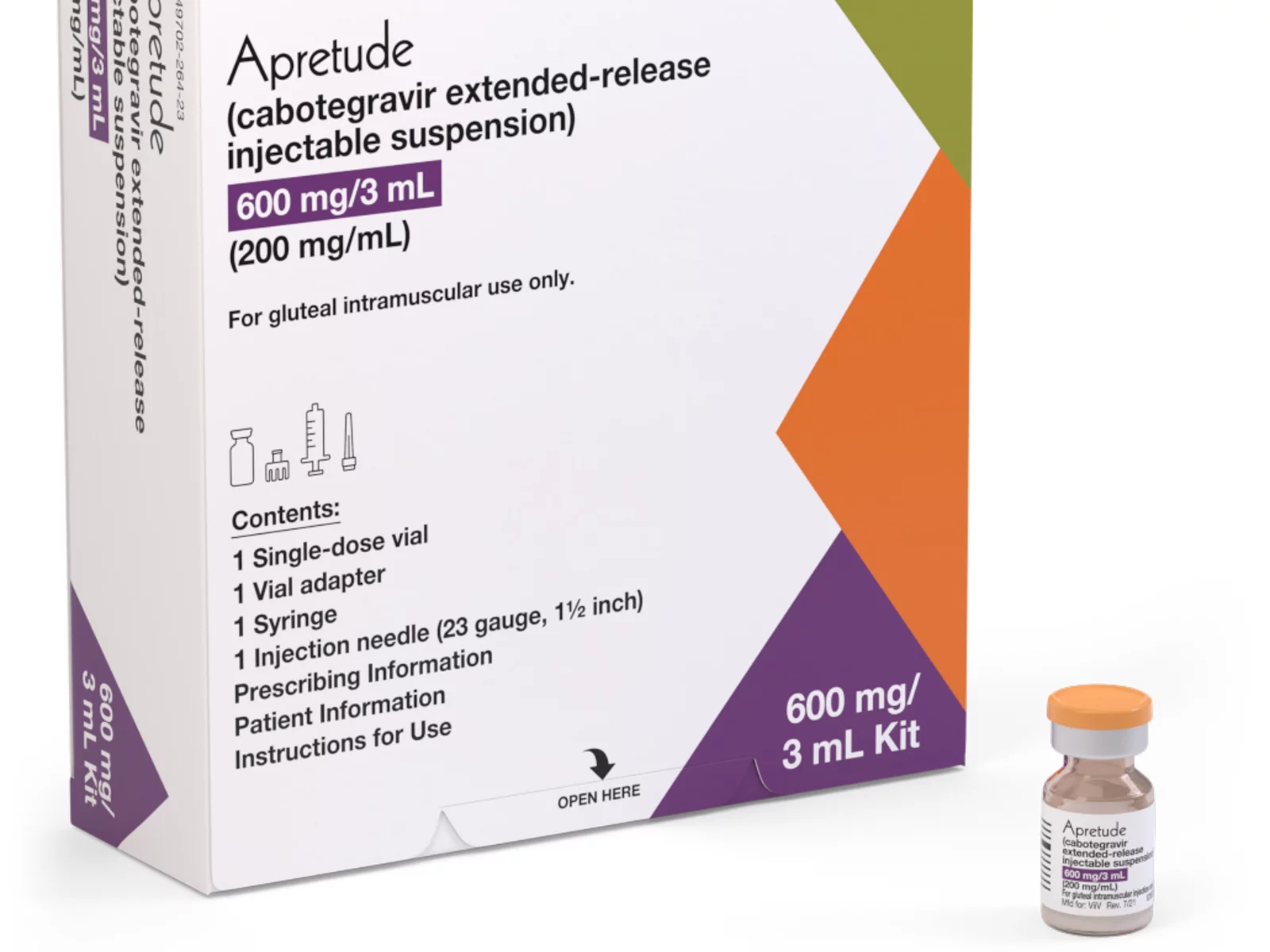

White House urged to expand PrEP coverage for injectable form

HIV/AIDS service organizations made call on Wednesday

A coalition of 63 organizations dedicated to ending HIV called on the Biden-Harris administration on Wednesday to require insurers to cover long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) without cost-sharing.

In a letter to Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the groups emphasized the need for broad and equitable access to PrEP free of insurance barriers.

Long-acting PrEP is an injectable form of PrEP that’s effective over a long period of time. The FDA approved Apretude (cabotegravir extended-release injectable suspension) as the first and only long-acting injectable PrEP in late 2021. It’s intended for adults and adolescents weighing at least 77 lbs. who are at risk for HIV through sex.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updated its recommendation for PrEP on Aug. 22, 2023, to include new medications such as the first long-acting PrEP drug. The coalition wants CMS to issue guidance requiring insurers to cover all forms of PrEP, including current and future FDA-approved drugs.

“Long-acting PrEP can be the answer to low PrEP uptake, particularly in communities not using PrEP today,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute. “The Biden administration has an opportunity to ensure that people with private insurance can access PrEP now and into the future, free of any cost-sharing, with properly worded guidance to insurers.”

Currently, only 36 percent of those who could benefit from PrEP are using it. Significant disparities exist among racial and ethnic groups. Black people constitute 39 percent of new HIV diagnoses but only 14 percent of PrEP users, while Latinos represent 31 percent of new diagnoses but only 18 percent of PrEP users. In contrast, white people represent 24 percent of HIV diagnoses but 64 percent of PrEP users.

The groups also want CMS to prohibit insurers from employing prior authorization for PrEP, citing it as a significant barrier to access. Several states, including New York and California, already prohibit prior authorization for PrEP.

Modeling conducted for HIV+Hep, based on clinical trials of a once every 2-month injection, suggests that 87 percent more HIV cases would be averted compared to daily oral PrEP, with $4.25 billion in averted healthcare costs over 10 years.

Despite guidance issued to insurers in July 2021, PrEP users continue to report being charged cost-sharing for both the drug and ancillary services. A recent review of claims data found that 36 percent of PrEP users were charged for their drugs, and even 31 percent of those using generic PrEP faced cost-sharing.

The coalition’s letter follows a more detailed communication sent by HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute to the Biden administration on July 2.

Signatories to the community letter include Advocates for Youth, AIDS United, Equality California, Fenway Health, Human Rights Campaign, and the National Coalition of STD Directors, among others.

-

Federal Government1 day ago

Federal Government1 day agoHHS to retire 988 crisis lifeline for LGBTQ youth

-

Opinions1 day ago

Opinions1 day agoDavid Hogg’s arrogant, self-indulgent stunt

-

District of Columbia1 day ago

District of Columbia1 day agoD.C. police seek help in identifying suspect in anti-gay threats case

-

Opinions1 day ago

Opinions1 day agoOn Pope Francis, Opus Dei and ongoing religious intolerance