Movies

The top 10 queer-centric movies of 2023

From ‘Rustin’ to ‘Barbie,’ it was a banner year in cinema

It’s been a great year for movies, we’re glad to say, but that’s made it harder than usual for us to compile our annual list of the 10 best queer-centric films. Still, we’ve made the hard calls necessary, and come up with our picks for the most outstanding of all the movies we’ve covered over the last 12 months.

You all know how these things work, so we won’t waste space with unnecessary explanations. Here, listed in reverse order, are the Blade’s Top Ten Films of 2023:

10. Rustin (Dir: George C. Wolfe)

Biopics face a difficult challenge when it comes to presenting an authentic portrayal of their subject: How do you encapsulate a person’s life into a two-hour story without relying on broad strokes? This frank and inspiring look at Civil Rights hero Bayard Rustin, whose monumental contribution to the movement was all-but-unsung for decades thanks to his open homosexuality, skirts the usual pitfalls by focusing on a specific episode in his career-orchestrating the 1963 March on Washington where MLK delivered his culture-shifting “I Have a Dream” speech – and delivering a behind-the-scenes snapshot of a seminal moment in American history at a time when stories about the triumph of activism feel more urgent than ever. Even so, it makes it onto our list mainly on the strength of star Colman Domingo, whose unapologetically thorny interpretation of the late queer icon is an engrossing – and refreshingly un-romanticized – powerhouse from start to finish.

9. Of An Age (Dir: Goran Stolevski)

What yearly “Best of” list would be complete without one or two under-the-radar gems? This Australian import (made in 2022, but released in the U.S. early this year) qualifies on both counts, but more importantly it’s a reminder that – despite frequent complaints to the contrary – there are great queer romance movies being made. This one is about two teens (Elias Anton and Thom Green) who spend a day together and fall hard for each other, but time and circumstance are not on their side; years later, reunited at a wedding, they find the connection between them has endured, but it may be too late to do anything about it. It’s a simple premise, and not much happens in terms of plot, but the winning authenticity of the love story it tells – and the way it captures unresolvable longing – is infinitely and universally relatable. It’s not a gay love story, it’s a love story between two people who happen to be gay, and that makes all the difference.

8. Rotting in the Sun (Dir: Sebastian Silva)

Even more under-the-radar, perhaps, is this out-of-left-field contender from out Chilean-born filmmaker Silva, who casts himself and real-life social media star Jordan Firstman as fictional versions of themselves in an outrageous, interwoven stream-of-events narrative that savagely satirizes the perpetually distracted state of self-obsessed modern culture while offering a darkly humorous commentary on cultural classism. It’s a lot to juggle in a single movie, but Silva pulls it off audaciously in a movie that does not go where you expect it to go and defies easy categorization by blending absurd farce with heartrending tragedy without missing a single beat. It also features un-simulated queer sex, and the fact that bold move is not the main attraction is itself testament to the power of this film’s unique vision. An MVP performance by veteran Chilean actress Catalina Saavedra is the richly satisfying icing on the cake.

7. Asteroid City (Dir: Wes Anderson)

This might be a controversial choice for us, given that critical response for this quintessentially Wes-Anderson-y think piece has been sharply divided and that the “queer factor” involved is relatively low; nevertheless, we stand by it, and only partly because the existential summer of “Barbenheimer” (more on that later) began with the quirky cult filmmaker’s visually stunning fantasia about a gathering of disparate characters in a kitschy New Mexican town for a government-sponsored “young inventors” competition during the height of 1950s-era “nuclear panic.” True to form, Anderson places meta-layers upon meta-layers by framing his narrative as a real-life theatrical play – penned by a queer playwright (Edward Norton) having a love affair with his leading man (Jason Schwartzman) – being memorialized in a TV documentary. And while this might make it hard for some to keep track of the story or identify with the characters, it also makes this movie into an almost perfect meditation on the way a cultural “zeitgeist” – in this case, the percolating dread that dominated world consciousness in the aftermath of the atomic bomb – manifests itself in our shared public imagination. An all-star cast of players (including Scarlett Johannson, Tom Hanks, Tilda Swinton and a host of others) only sweetens the pot.

6. May December (Dir: Todd Haynes)

It may be no surprise to see the latest film by “new queer cinema” icon Haynes on our list, but rest assured we’re not the only ones to recognize the brilliance of this uncomfortable character study in which a Hollywood actress (Natalie Portman), hired to star in a docudrama about a real-life tabloid sex scandal involving the inappropriate relationship and subsequent marriage between an adult woman (Julianne Moore) and an underage boy, descends on the couple’s household, stirring up long-unaddressed feelings for each of them as she loses herself in the persona of her role. Steeped in the tranquilizing suburban blandness that has always been a hallmark of Haynes’ melancholy, subversively divergent milieu, it’s the kind of movie that feels like a fever dream and leaves you grappling with issues you thought you’d worked out for yourself years ago – and while Portman and longtime Haynes muse Moore both deliver their usual stellar performances, it’s Charles Melton’s unexpectedly nuanced turn as the now-adult object of Moore’s transgressive desires that provides its troubled heart.

5. Oppenheimer (Dir: Christopher Nolan)

OK, there’s not really a specific queer angle to this introspective, epic-length film about the man who built the atom bomb, but the themes and questions it forces us to confront – all tied to the looming specter of effectively instant worldwide annihilation we’ve been living with ever since the nuclear blasts that brought WWII to an abrupt and sobering end – make it essential viewing anyway. Centered on the white-knuckle intensity of Cillian Murphy’s performance in the title role and bolstered by equally invested work from an all-star ensemble of supporting players (Emily Blunt, Robert Downey, Jr., Matt Damon, and more), Nolan’s finely wrought biopic becomes a meditation on responsibility, blame, the madness of mutually assured destruction, and – most significantly of all – living with an omnipresent sense of inevitable doom. Yet as depressing as all that sounds, the film resonates with enough humanity and compassion – even for its most ethically challenging characters – that we can walk away from it with something that feels almost like hope.

4. All of Us Strangers (Dir: Andrew Haigh)

Invading our list from the UK is the latest film from the writer/director who raised the bar for queer romance movies with 2011’s “Weekend,” a haunted (literally) love story in which a lonely London screenwriter (Andrew Scott) communes with the ghosts of his long-deceased parents (Claire Foy, Jaime Bell) while beginning a tentative relationship with a handsome but palpably sad neighbor (Paul Mescal). Based on a novel by Japanese author Taichi Yamada, it’s a ghostly tale more esoteric than supernatural, driven by mood, draped in primary colors, and infused with life through the tenderness between its two fragile lovers, less interested in the details of a hypothetical afterlife than it is in the bonds of love – in all its forms – which connect us to each other beyond time and mortality. Sure, it’s gloomy on the surface, and it brushes up against sorrows that are mercifully unfathomable to many of us, but it somehow manages to leave us uplifted rather than unsettled – and almost as a bonus, the sweet-and-sexy chemistry between its leading men will stick with you long after the final credits roll.

3. Saltburn (Dir: Emerald Fennell)

We’re not going to lie: part of what earns this gnarly, aggressively twisted movie a high place on our list is its audaciousness. In its tale of Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan), a working class lad on scholarship to Oxford whose infatuation with a charismatic and wealthy classmate (Jacob Elordi) leads to a debauched and treacherous summer at the elegantly dilapidated country estate of the title, it turns a vaguely Dickensian story of fate, irony, and social commentary into an escalating wild ride that takes us places we don’t expect to go and never wanted to see, and it makes us love every guilty second of it. Yes, it’s dark and depraved, an over-the-top, starkly satirical look into the casually cruel world of the “ruling class” that forces us to ask just how far we would be willing to go to become a part of it, and it uses our own expectations against us to deliver a bombshell ending that might feel like a slap in the face for those who aren’t paying close attention (and possibly for those who are, too) – but all of that gives us even more reason to laud this second effort from the daring writer/director of “Promising Young Woman” as one of the most thrilling and unforgettable cinematic experiences of the year.

2. Killers of the Flower Moon (Dir: Martin Scorsese)

Like “Oppenheimer,” there’s no direct queer thread to be found in this late-career masterpiece from one of America’s most accomplished cinema artists, but its exploration of the deeply embedded racism that has been woven throughout our nation’s history has obvious resonance for anyone whose status as an “other” places them at risk of exploitation, oppression, and worse in a culture that is stacked against them. Based on the non-fiction book by David Gann, it chronicles a conspiracy in 1920s Oklahoma in which the indigenous Osage community, made rich by the oil fields under its tribal land, was robbed of its wealth by local white business leaders through a systematic campaign of marriage and murder, and the efforts of the then-fledgling FBI to bring the perpetrators to some kind of justice. With career-highlight performances from Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert DeNiro, as well as a revelatory turn from indigenous actor Lily Gladstone, there’s more than enough great acting to keep us mesmerized throughout its three-and-a-half-hour runtime – and the same understanding of the pathology of corruption that Scorsese deployed in his classic sagas about organized crime breathes powerful insight into a story that has just as much to say about the America we live in today as the one in which it takes place.

1. Barbie (Dir: Greta Gerwig)

When we first predicted this would be the movie of the year, our tongue may have been firmly planted in our cheek – but we’re not sorry to be able to say we were right. Not just a campy fantasy about a doll, it’s a truth bomb delivered in a candy-colored Trojan Horse, in which an unexpected existential crisis (do we detect a running theme in this year’s movies?) sends Barbie (Margot Robbie) into the human world looking for answers and ends up turning her own world upside down as Ken (Ryan Gosling), having seen the glories of “the patriarchy”, tries to remake Barbieland in his own image. It’s a premise that gives Gerwig (and partner Noah Baumbach, with whom she co-wrote the screenplay) plenty of fodder to skewer contemporary culture, and she takes aim at all the usual targets as she gleefully spreads the kind of progressive, humanitarian, pro-feminist, socially ethical messaging that conservative pundits like to fall over themselves dismissing as “woke” propaganda. But that’s not the endgame in this transcendent wonder of a movie, because Gerwig and company take things beyond the dualistic dogmas that stymie us in our quest for a more equitable world to ask some much deeper questions, creating a piece of absurdist cinema with as much intellectual weight as any film you’re ever likely to see. Of course, viewers hung up on the “culture war” talking points being batted around from every direction might not notice, any more than they are likely to notice the comprehensive array of nods and tributes she pays along the way to the iconic movies that inspired her, but one of the many joys of “Barbie” is that it reveals more with each repeat viewing – so there’s always hope they’ll catch on, eventually.

Oh, and even if the only queer content it contains comes in the form of deliciously unsubtle innuendo, there’s something quintessentially queer about it – and we’re not just talking about the color palette.

Movies

‘Outstanding’ doc brings overdue spotlight to lesbian activist Robin Tyler

‘Whatever they do to us, they need to know that there will be consequences’

In the new Netflix documentary “Outstanding: A Comedy Revolution” – now streaming on the Netflix platform – filmmaker Page Hurwitz takes viewers behind the scenes of a landmark 2022 performance featuring an all-star lineup of queer stand-up comedians. She also reveals the powerful queer activism that has been pushing mainstream boundaries over the past five decades and beyond through a collection of out-and-proud comics that reads like a “who’s who” of queer comedy icons.

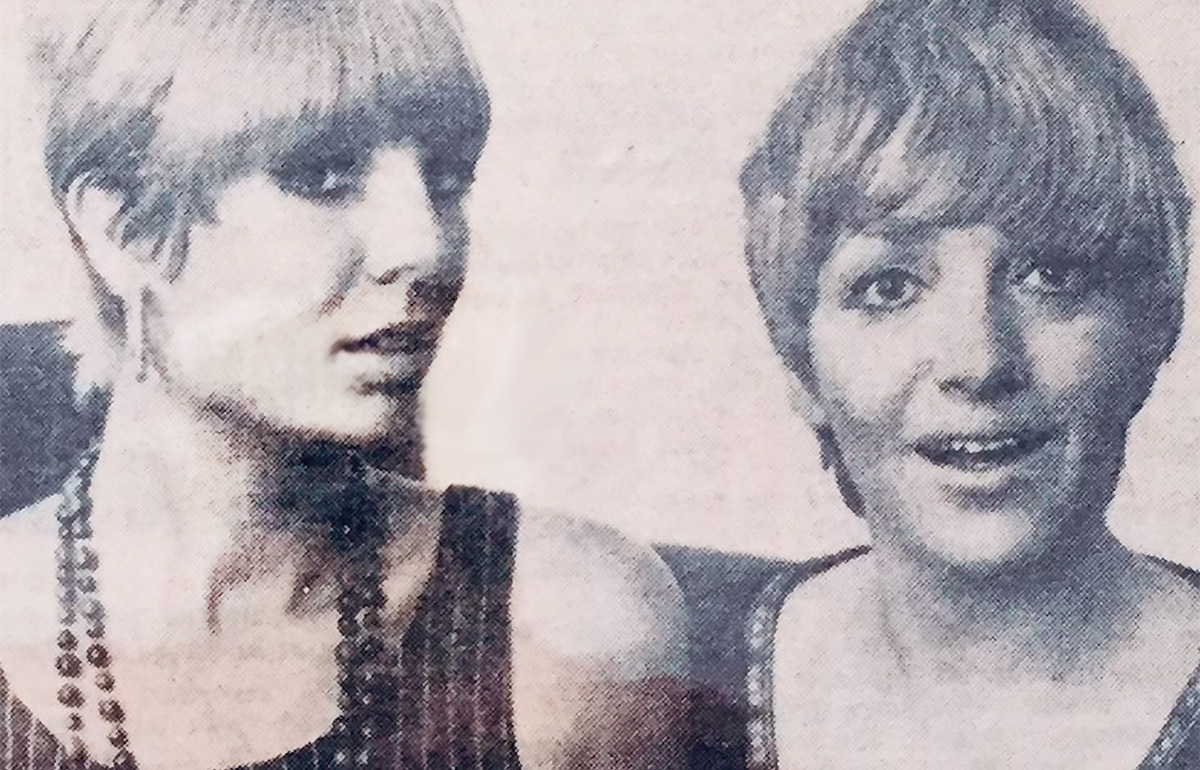

In doing so, its spotlight inevitably lands on Robin Tyler, who – after becoming the first lesbian comic to come out on national television and co-starring in a network series with her partner, Pat Harrison – incurred the wrath of sponsors (after an on-air remark aimed at notorious anti-LGBTQ mouthpiece Anita Bryant) and wound up unceremoniously dropped by the network.

Tyler persisted, and her passion led her to activism, where her contributions are likely well known to many Blade readers. She organized and produced the first three national marches on Washington for LGBTQ rights, including 1987’s “mock wedding” of hundreds of queer couples; she and her future wife (the late Diane Olsen) were the first couple to sue the state of California for the right to be married — leading to the seven-year legal battle that culminated in marriage equality. If you are currently in a same-sex marriage in the United States, you have her to thank.

We spoke to her about the film and her legacy, and, as always, she pulled no punches. Our conversation is below.

BLADE: ‘Outstanding’ highlights your removal from “prime time” as a setback for queer visibility, but do you still think of it as a setback for your career?

ROBIN TYLER: You know what? Everybody says, “Oh, she gave up this career, she could have been a star,” but what they mean is I could have gotten mainstream acceptance. It’s like saying to Richard Pryor: “If you didn’t tell the truth, maybe white people would have loved you.” The best thing that happened to us is that we didn’t get picked up, because then we could go and be free. It takes your life away, having to live a lie. We gained our freedom and lost nothing.

I don’t care about mainstream acceptance, if it means being in the closet. Don’t forget, 75 million Americans are MAGA supporters. To me, that’s the mainstream.

BLADE: As an organizer, you spearheaded the fight for marriage equality. How did that happen?

TYLER: In 1987, two men from L.A. wanted me to do the “mock wedding” as part of the ‘87 march on Washington. I took it to the board – there’s always this board of 68 people, it’s different people, but the same attitude, with every march – and they voted it down. They said, ‘no one’s interested in marriage,” and I said “fine.” And I did it anyway, and 5,000 people came. Obviously it was an issue we were interested in.

It was also interesting that a march board would try to decide what people want or not. Well, we did want it, and we got it, now.

BLADE: And yet, it seems we’re still fighting for it.

TYLER: I agree, and I think with this Supreme Court we’re in trouble – but passion is much better than Prozac, so we need to keep aware and be ready to get into the streets again. We can’t just be “armchair activists” on the internet, you know? Because then we’re just reading to each other.”

BLADE: It does seem that the internet has made it easier for us to live in our comfortable bubbles.

TYLER: Yeah, but I’m an organizer, and it’s wonderful for that. I was the national protest coordinator when we stopped Dr. Laura [Schlesinger, the anti-LGBTQ talk radio “psychotherapist” whose transition to television was successfully blocked by community activism in the early 2000s], and we did all the demonstrations locally. We worked with a guy who knew the internet, and we were able to send out information all over the country for the first time. I remember when we just had to go to parades and bars and baseball fields and had to leaflet everyone. This is easier. Less walking.

BLADE: Still, social media has become a space where “cancel culture” seems just to divide us further.

TYLER: That term was created by the right. They can go ahead and say anything they want, but we get to not be called names anymore. At least we have a way to fight back. They call it “cancel culture” and we call it “defending our rights.”

And you know what? Even today, people like Dave Chappelle are doing homophobic jokes, and it’s not just that they’re doing it, it’s that these people sitting in the audience are still laughing at it. They still think they can get away with ridiculing us. You can always punch down and get a laugh. And why is it so bad, with people like Chappelle or Bill Maher? Because anytime you dehumanize anybody, when you snicker at them because you don’t understand, you’re giving other people permission to attack them. They’re attacking these people that are being brutally murdered, and they’re using humor as the weapon.

We didn’t accept it in the ‘70s, so why are we accepting it now? And why aren’t we calling out Netflix for giving it a platform? It’s not enough to put out “Outstanding” and showcase pro-gay humor. If a comic says something racist, their career is over, yet it’s OK for Chappelle to do homophobic stuff? What if I stood up and changed what he’s saying to make it about race instead of transgender people?

And it’s not just about “right” vs. “left” anyway. Even with the Democrats in, they never deliver. Since 1970, they promised us a “gay civil rights bill,” and we still don’t have one. Why not? Democrats have held power in Congress, the Senate, the presidency, and they never pushed it through. We still can’t rent in 30 states, we can get fired; the United States is not a free country for queer people, and we must hold the government accountable. We have to fight for marriage separately, we have to fight for this and that, separately – and all it would take is one bill!

It’s been 54 years. Isn’t it time? We have to look at who our friends are – but don’t get me wrong, I’m still voting for Biden.

BLADE: So, how do we fix it?

TYLER: Here’s what I believe in: a woman walks into a dentist office, and he’s about to drill her teeth when she grabs him by the balls and says, ‘We’re not going to hurt each other, are we?’ I believe in that approach. Whatever they do to us, they need to know that there will be consequences.

And, also, at Cedars-Sinai they have just one channel in the hospital, and it’s comedy, because laughter is healing. Maybe we should we end on that?

Movies

Gender expression is fluid in captivating ‘Paul & Trisha’ doc

Exploring what’s possible when you allow yourself to become who you truly are

Given the polarizing controversies surrounding the subject of gender in today’s world, it might feel as if challenges to the conventional “norms” around the way we understand it were a product of the modern age. They’re not, of course; artists have been exploring the boundaries of gender – both its presentation and its perception – since long before the language we use to discuss the topic today was ever developed. After all, gender is a universal experience, and isn’t art, ultimately, meant to be about the sharing of universal experiences in a way that bypasses, or at least overcomes, the limitations of language?

We know, we know; debate about the “purpose” of art is almost as fraught with controversy as the one about gender identity, but it’s still undeniable that art has always been the place to find ideas that contradict or question conventional ways of viewing the world. Thanks to the heavy expectation of conformity to society’s comfortable “norms” in our relationship with gender, it’s inevitable that artists might chafe at such restrictive assumptions enough to challenge them – and few have committed quite so completely to doing so as Paul Whitehead, the focus of “Paul & Trisha: The Art of Fluidity,” a new documentary from filmmaker Fia Perera which enjoyed a successful run on the festival circuit and is now available for pre-order on iTunes and Apple TV ahead of a VOD/streaming release on July 9.

Whitehead, who first gained attention and found success in London’s fertile art-and-fashion scene of the mid 1960s, might not be a household name, but he has worked closely with many people who are. A job as an in-house illustrator at a record company led to his hiring as the first art director for the UK Magazine Time Out, which opened the door for even more prominent commissions for album art – including a series of iconic covers for Genesis, Van der Graaf, Generator, and Peter Hammill, which helped to shape the visual aesthetic of the Progressive Rock movement with his bold, surrealistic pop aesthetic, and worked as an art director for John Lennon for a time. Moving to Los Angeles in 1973, his continuing work in the music industry expanded to encompass a wide variety of commercial art and landed him in the Guinness Book of World Records as painter of the largest indoor mural in the world inside the now-demolished Vegas World Casino in Las Vegas. As a founder of the Eyes and Ears Foundation, he conceived and organized the “Artboard Festival”, which turned a stretch of L.A. roadway into a “drive-through art gallery” with donated billboards painted by participating artists.

Perera’s film catches up with Whitehead in the relatively low-profile city of Ventura, Calif., where the globally renowned visual artist now operates from a combination studio and gallery in a strip mall storefront. Still prolific and producing striking artworks (many of them influenced and inspired by his self-described “closet Hinduism”), the film reveals a man who, far from coming off as elderly, seems ageless; possessed of a rare mix of spiritual insight and worldly wisdom, he is left by the filmmaker to tell his own story by himself, and he embraces the task with the effortless verve of a seasoned raconteur. For roughly the first half of the film, we are treated to the chronicle of his early career provided straight from the source, without “talking head” commentaries or interview footage culled from entertainment news archives, and laced with anecdotes and observations that reveal a clear-headedness, along with a remarkable sense of self-knowledge and an inspiring freedom of thought, that makes his observations feel like deep wisdom. He’s a fascinating host, taking us on a tour of the life he has lived so far, and it’s like spending time with the most interesting guy at the party.

It’s when “Art of Fluidity” introduces its second subject, however, that things really begin to get interesting, because as Whitehead was pushing boundaries as an in-demand artist, he was also pushing boundaries in other parts of his life. Experimenting with his gender identity through cross-dressing since the 1960s, what began tentatively as an “in the bedroom” fetish became a long-term process of self-discovery that resulted in the emergence of “converged artist” Trisha Van Cleef, a feminine manifestation of Whitehead’s persona who has been creating art of her own since 2004. Neither dissociated “alter ego” nor performative character, Trisha might be a conceptual construct, in some ways, but she’s also a very authentic expression of personal gender perception who exists just as definitively as Paul Whitehead. They are, like the seeming opposites of yin and yang, two sides of the same fundamental and united nature.

Naturally, the bold process of redefining one’s personal relationship with gender is not an easy one, and part of what makes Trisha so compelling is the challenge she represents to Paul – and, by extension, the audience – by co-existing with him in his own life. She pushes him to step beyond his fears – such as his concerns about the hostile attitude of the shopkeeper next door and the danger of bullying, brutality, and worse when Trisha goes out in public – and embrace both sides of his nature instead of trying to force himself to be one or the other alone. And while the film doesn’t shy away from addressing the brutal reality about the risk of violence against non-gender-conforming people in our culture, it also highlights what is possible when you choose to allow yourself to become who you truly are.

As a sort of disclaimer, it must be acknowledged that some viewers may take issue with some of Whitehead’s personal beliefs about gender identity, which might not quite mesh with prevailing ideas and could be perceived as “problematic” within certain perspectives. Similarly, the depth of his engagement with Hindu cosmology might be off-putting to audiences geared toward skepticism around any spiritually inspired outlook on the world. However, it’s clear within the larger context of the documentary that both Paul and Trisha speak only for themselves, expressing a personal truth that does not nullify or deny the personal truth of anyone else. Further, one of the facets that gives “Art of Fluidity” its mesmerizing, upbeat charm is the sense that we are watching an ongoing evolution, a work in progress in which an artist is still discovering the way forward. There’s no insinuation that any aspect of Paul or Trisha’s shared life is definitive, rather we come to see them as a united pair, in constant flux, moving through the world together, as one, and becoming more like themselves every step of the way.

That’s something toward which we all would be wise to aspire; the acceptance of all of our parts and the understanding that we are always in the process of becoming something else would certainly go a long way toward making a happier, friendlier world.

Movies

New Cyndi Lauper doc brings overdue spotlight to queer ally

‘Let the Canary Sing’ captures a unique, era-defining star

Every era in our cultural memory has given rise to popular artists that helped to define them, but few can be said to have made as definitive an impact as Cyndi Lauper in the early ‘80s. Splashing onto our airwaves and across our television screens (courtesy of the newly minted MTV) with a defiantly upbeat and colorful blast of society-shifting energy, her proclamation that “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” caught the world off guard with a feminist anthem disguised as a good-time party song, and her sense of quirky punk style became an iconic influence over the “look” of an entire decade. In some ways, you could almost say Cyndi Lauper was the ‘80s.

For many people who grew up or came of age during her rise from unknown girl singer to pop music phenomenon, that might be the extent of their knowledge of her life and career. Despite the success (and Grammy Award) she achieved with her first few hits, the ever-roving eye of public attention inevitably moved on to the next new superstar, and her later efforts – while not exactly ignored – never managed to garner as much attention.

That doesn’t mean she has been inactive, though, as her die-hard fans (and there are many) well know; this is especially true in the queer community, where she has long been recognized and celebrated as a staunch ally – which is why it seems apt that Pride month should coincide with the release of “Let the Canary Sing,” a new documentary profile of Lauper that premieres on Paramount Plus this week.

Directed by Emmy-winning documentarian Alison Ellwood, “Canary” takes its name from a comment made by the judge in a legal case that opened the door for Lauper’s stardom – no spoilers here, you’ll have to watch the movie to find out more. It undertakes the telling of a well-rounded and comprehensive life story to cast that stardom in a new light. Maintaining a comfortable sense of chronology, it begins with Lauper’s childhood, growing up in Brooklyn (and later, Queens) in a close-knit family as the middle child of three with a divorced single mother, and follows the trajectory of her life – rebellious, risk-taking teen to driven, passionate artist and activist – through her love of music, her rise to fame, her struggle to evolve in an industry that rewards predictable familiarity, her emergence as an LGBTQ advocate, and her expansion into a genre-leaping artist whose reach has extended beyond pop culture to earn her renown for her versatility. It also covers her accomplishment as the first woman to win a Tony Award as sole composer of the music and lyrics of “Kinky Boots,” the Harvey Fierstein-scripted drag-themed Broadway musical which made a star of Billy Porter – and nabbed her another Grammy (for its Original Cast Recording), to boot. Bolstered by extensive current interview footage with Lauper herself, as well as elder sister Elen, younger brother Fred, and other important figures from her personal and professional life, it finds an arc that reveals its subject as an authentic and uncompromising visionary dedicated to “lifting up” the entire human race.

That would sound hyperbolic – and probably more than a little disingenuous – if Lauper did not come across so palpably on camera. Whether it’s footage from a decades-old Letterman show or newly filmed commentary shot specifically for the film, her “true colors” come shining through (forgive us for that one, we couldn’t resist) to provide ample evidence that, even if she didn’t always know where she was going, she always knew it would be the direction of her own choosing. Indeed, as the movie makes clear, much of the reason behind Lauper’s fade from the pop spotlight was the result of her refusal to repeat herself, to compromise her own path by delivering pale copies of the formula that had made her an “overnight success” after 15 years of trying. Although the documentary doesn’t insinuate this, it’s impossible for us not to suspect that homophobic backlash following her public embrace and advocacy of the queer community – something surely intertwined with her close bond to sister Elen, an out lesbian who is positioned in Ellwood’s film as a key pillar of both emotional and artistic support in Lauper’s life – may have had something to do with the mainstream music industry’s ambivalence toward her as she pursued her artistic impulses beyond the flashy appeal of her debut album.

In any case, “She’s So Unusual,” as a debut album title, proved to be an ironic foreshadowing of the very reasons she was unable to “stay in her own lane” well enough to remain in the good graces of a public (or, perhaps more truthfully, of record executives) that only wanted more of the same. Lauper has never been one to conform, and it’s made her vulnerable, like so many other unrelenting female voices both before and after her, to the mainstream insistence on reinforcement of the comfortable over the breaking down of boundaries.

“Let the Canary Sing” captures all of this succinctly, yet with layered and sophisticated nuance, as it pays its tribute to a pop icon whose seminal work has continued to resonate after more than 40 years. Unavoidably, perhaps, it sometimes feels like a “Behind the Music” episode or a “puff piece” for an artist about to launch a new project – indeed, Lauper announced a “farewell tour” of 23 cities, as well as a “companion piece” greatest hits album release, on the eve of the movie’s streaming debut – but it pushes past such irrelevant comparisons thanks to the palpable sincerity conveyed onscreen, not only from her, but from all the people in her orbit whose comments about her are included in the film.

Of course, it must be said that anyone who’s not a “Cyndi Lauper fan”, whether by virtue of generational gaps or personal tastes, will probably not be drawn to watch a filmic love letter to her, and that’s a shame. It (and she) has the power to make viewers into true believers not only in her talent, but in her message of acceptance, inclusion, and unconditional love. Part of that, hinges on Ellwood’s skill as a filmmaker and teller of real-life stories, but the lasting impact rests on the persona of the star herself, who exudes a genuine air of transcendence and makes us not only feel instantly comfortable, but completely “seen” and validated, no matter who we are or which spectrum we might be on.

It’s hard to fake the kind of sincerity that makes that possible, and nothing about “Canary” suggests that Cyndi Lauper has any interest in being fake, anyway.

-

Canada1 day ago

Canada1 day agoToronto Pride parade cancelled after pro-Palestinian protesters disrupt it

-

Theater4 days ago

Theater4 days agoStephen Mark Lukas makes sublime turn in ‘Funny Girl’

-

Baltimore3 days ago

Baltimore3 days agoDespite record crowds, Baltimore Pride’s LGBTQ critics say organizers dropped the ball

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoHaters troll official Olympics Instagram for celebrating gay athlete and boyfriend