Movies

Miyazaki caps career with masterful ‘Boy and the Heron’

A treatise on the need for harmony between man and nature

If anyone can be said to rival the impact of Walt Disney on the field of animated films, it’s Hayao Miyazaki. Co-founder of Studio Ghibli, his work in Japan’s anime genre is legendary, with films like “My Neighbor Totoro,” “Kiki’s Delivery Service,” “Howl’s Moving Castle,” and the Oscar-winning “Spirited Away” – which held the record as the highest-grossing film in Japanese history for 19 years – expanding his popularity and helping to build a global entertainment empire that, like Disney’s, includes merchandise, licensing, and even a theme park.

Millions of fans worldwide – many of them queer – have grown up loving his movies not just for their unique blend of the fanciful, the poignant, and the profound but for the sublime visual artistry and masterful storytelling with which they are rendered.

Now 83, the revered animator announced his retirement from making feature films in 2013 – only to start work, three years later, on another one. Seven years afterward, that project reached fruition with “The Boy and the Heron,” released in its native Japan last summer. And if any proof is needed to stand as testament to Miyazaki’s popularity, it can be found in the fact that, in spite of a deliberately minimal promotion strategy (the film was released with no teasers, trailers, or fanfare besides a single poster image), it had the biggest opening weekend of any Studio Ghibli film to date, going on to become the first original anime film (and the first film by Miyazaki) to achieve number one status at the box office in both Canada and the U.S.

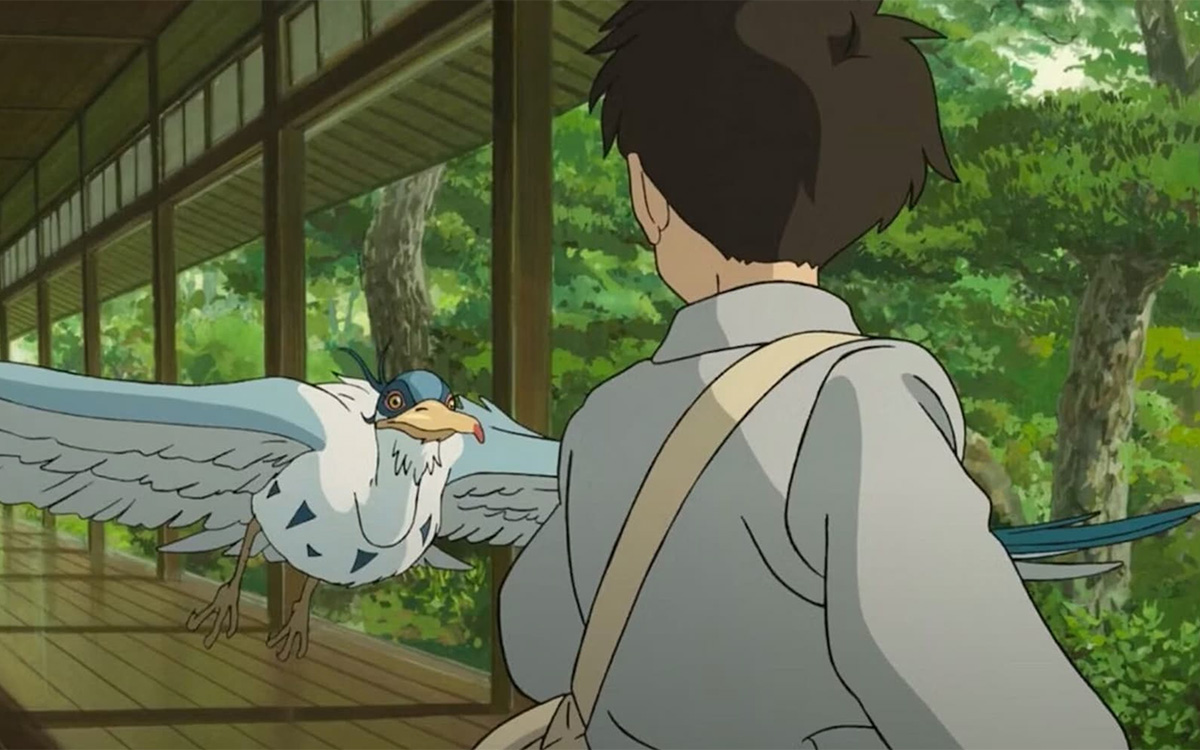

Initially released in the latter country on Dec. 8, and still in theaters in the wake of its Golden Globe win and Oscar nomination as Best Animated Film of 2023, “Heron” – written and directed by Miyazaki and inspired by (though otherwise unrelated to) Genzaburō Yoshino’s 1937 novel “How Do You Live?” – is an autobiographically leaning story centered on young Mahito (Soma Santoki / Luca Padovan in the English dubbed version), a boy growing up in Tokyo during World War II. Following the death of his mother in a hospital fire, his industrialist father (Takuya Kimura / Christian Bale) soon remarries, with his late wife’s younger sister (Yoshino Kimura / Gemma Chan) as his new bride, and Mahito finds himself living at her family’s estate in the rural countryside. There, a mysterious – and persistent – heron (Masaki Suda / Robert Pattinson) seems to take interest in him, and he begins to feel taunted by its attentions – but when his new stepmother disappears into the surrounding forest, the bird leads him into an overgrown tower, where a seemingly all-powerful lord (Shōhei Hino / Mark Hamill) rules over a hidden underworld, and he embarks on an epic quest through its mystical landscape to rescue her, helped along the way by a swashbuckling fisherwoman (Ko Shibasaki / Florence Pugh) and a guardian fire spirit (Aimyon / Karen Fukuhara) – discovering the secrets of a magical family history stretching back across generations as he goes.

Considering its unmistakable parallels to Miyazaki’s real-life childhood (his father, like Mahito’s, was an industrialist working for a company that manufactured war planes, allowing him an affluent and somewhat sheltered upbringing in a devastated Japan), it’s impossible not to see his latest movie as a “swan song.” Indeed, it was widely branded as such by journalists ahead of its release, and the director himself declared it his “last,” though that has since been recanted by Studio Ghibli with the announcement that he is working on another. Still, while it may not be his final manifesto, it would certainly be a worthy one.

Infused with the filmmaker’s signature recurring themes – the need for harmony between man and nature, the paradoxical absurdities of technology, the value of traditional lifestyles and the importance of craft and artistry, the conflict between pacifist ideals and violence that dominates human affairs – and weaving a mythic tale that postulates a deeper reality where life and death are forever intertwined in a realm of impermanent permanence, “Heron” feels as much like a statement of belief as it does a fantasy. One might even sense that there’s an insistence that it can be both, and that life itself is a sort of fantasy, capable of being shaped by things that exist only within our imaginations, and that, of course, is the source of its power.

Such cosmic speculations aside, however, Miyazaki’s movie hooks us not with its esoteric metaphysics, but with its meditations on loss, grief, and the challenge of finding peace in a world that often seems dominated by chaos and indiscriminate destruction. Artfully framed to suggest that the “fantasy” elements of its plot either might or might not exist only within its youthful protagonist’s delirious, wounded mind, it touches us to the heart with the harsh realities of Mahito’s young life; the opening sequence, depicting the fire that kills his mother, is horrific, leaving its shadow on the rest of the film even as it does on Mahito’s soul, and his grief, compounded and left unreconciled by his loving-but-ham-handed father’s seeming refusal to address or even acknowledge it, resonates on a universal wavelength simply because it is so fundamentally human. It’s in grappling with these elements of life – the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” to which Shakespeare refers in “Hamlet,” a play which is, perhaps not coincidentally, echoed in an inverted form within the structure of Miyazaki’s narrative – that the movie brings a sense of truth to the magical realism it embraces. The comforts it offers do not feel like hollow platitudes; rather, they point us toward wisdom, much in the way of a riddle told by a Zen Master, and a way of looking at the world that is comfort enough in itself.

Yet “The Boy and the Heron” is not made of the kind of late-career introspection that robs it of its sense of fun. Full of adventure, action, and the filmmaker’s signature blend of gorgeously animated realism with adorable absurdity inspired by Kawaii (Japanese “cute culture”), it offers as much spirited adventure and comedic flair as expected from a Miyazaki film– and it’s populated with just as many whimsically grotesque creatures and characters, to boot.

Needless to say, perhaps, it’s also a stunning film to behold, evoking a classic Japanese woodcut brought to life and infused with a powerful spirit of its own; though enhanced and aided by modern technology, the animation – as with all of Miyazaki’s work – is hand-drawn, making its visual perfection even more breathtaking. Add to all this the beautiful score by longtime friend and collaborator Joe Hisaishi, and the result is irresistible.

Given that “The Boy in the Heron” is likely a top contender for the win at this year’s Oscars, it’s likely to be accessible on the big screen – in some markets, at least – for a while before it becomes available for streaming. Whether or not you can see it now, keep it on your radar – we don’t use the word “masterpiece” lightly, but we suggest this one might qualify, and you owe it to yourself to watch it so that you can decide for yourself.

We’re pretty sure you’ll agree.

Movies

An ‘Indian Boy’ challenges family tradition in sweet romcom

Refreshing look at what is possible when a family is willing to make changes

For queer audiences hungry for representation, nothing says “I feel seen” quite as much as a good queer romcom.

Perhaps it’s because love stories are universal, differing from culture to culture in the surface details only, and therefore have the potential for helping straight audiences understand a different kind of love a little better; or perhaps, in seeing our kind of love displayed so publicly, we feel a sense of validation. Whatever the reason, it rings our bell.

Maybe that’s why the quest for the first “great gay romcom” has continued to be a driving factor in the ongoing history of queer cinema, setting up an expectation in the mainstream that has, perhaps inevitably, fallen short of creating it. Fortunately, there are some efforts that have risen above the pressure to simply be what they are, instead of being the answer to everybody’s prayers for acceptance, and in so doing have managed to come close.

“A Nice Indian Boy” is just that kind of movie. Adapted from a play by Madhuri Sheka (by Eric Randall, whose screenplay made Hollywood’s buzzy “Black List” of un-produced scripts in 2021) and directed by Canadian-born Indian filmmaker Roshan Sethi, it might come closer to presenting an entirely successful gay romcom than most of the other overthought efforts that have come before.

It centers on Naveen (Karan Soni), a 30-something gay doctor, whose South Asian Indian family has long since accepted and supported his orientation but still struggles to reconcile it with their traditional beliefs. Enter Jay (Jonathan Groff), a white freelance photographer who grew up as an adoptee to Indian parents, and of course it’s love at first sight. A whirlwind courtship leads to a proposal, but there are a lot of considerations that must be met before the smitten couple can achieve the “big Indian wedding” of their dreams. The one that looms largest is gaining the approval of Naveen’s progressive-but-devout Hindu parents (Harish Patel and Zarna Garg) – not to mention his discontented sister (Sunita Mani) – whose confusion over his new fiancé’s ethnicity is just one of many obstacles they face in making their dream nuptials a reality. Intensifying that challenge – frequently to comedic effect – is Naveen’s struggle with his own insecurities, which threaten to derail not only the wedding plans but his relationship with the emotionally open and unreservedly passionate Jay, too.

It’s a sweet and clearly heartfelt affair, with a few laugh-out-loud moments to be found, as well as the wry introspection of its neurotic lead character, whose self-questioning turmoils feel like a connecting thread to the work of Woody Allen – indeed, “Annie Hall” is even name-dropped in the film, suggesting a spirit of homage that can be traced in a reflection of that classic Oscar-winner’s title character through Jay’s quirkily unconventional personality.

At the same time, the movie marries its diverse cultural influences by drawing just as heavily from a love of “Bollywood” cinema, and one of its movies in particular, which both of its protagonists adore. That allows it to maintain an aura of lush, larger-than-life romanticism that counterpoints the amusingly endearing self-deprecation of its main protagonist; it also reflects in the movie’s colorful, lively visual aesthetic and its choice to share focus on an entire family of characters for a more sweeping perspective.

As for its handling of the subject of race, despite its clear (and queer) twist on the “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?” trope of a family’s surprise over a bi-ethnic romance in its midst, “Indian Boy” doesn’t spend much time worrying about a love connection shared across racial divides; and while it gets considerable comic mileage out of Naveen’s parents’ well-intentioned but clueless efforts to show their acceptance of their gay son, the queerness of his relationship is not really an issue in itself. Rather, the conflict comes – for all of the movie’s primary characters, not just for the couple in the middle – from the difficulty of finding harmony between old customs and a new world that no longer fits within their boundaries.

Admittedly, Sethi’s movie sometimes feels a little too sentimental to be believed; it paints an aspirational picture – a true-love romance between a successful doctor and a rising artist – and tugs even harder on our heartstrings with its depictions of clumsy-but-sincere acceptance from the family around them; and while we don’t want to spoil any surprises, when it comes time for the big finale, it pulls out all the feel-good stops. Cynics in the audience might fail to be as enchanted as it wants them to be.

And yet, it all works wonderfully, largely because of its cast. Soni and Groff have an instantly tangible chemistry, and their differing personalities complement each other perfectly. Individually, they take us with them on their personal journeys with just as much clarity and conviction, and the movie would fall flat without the strength of their performances at its core.

Equally superb, however, are Patel and Garg, whose discomfort over the preparations for their son’s wedding never feel like they come from anywhere but love and a desire to share in his happiness; and Suri, whose considerable comedic talents contrast to great effect with the brewing discord within her character, lends a much-needed weight to the mix while still managing to glow alongside all her costars.

Combined with the sharp, funny, and insightful script and the generosity of Sethi’s directorial approach, which frames each character with respect and import to the story, it all makes “A Nice Indian Boy” a nice crowd-pleasing movie to see. It may or may not be “the great gay romcom,” and it might all seem a bit too glossy and perfect for some viewers’ taste – but it offers a refreshing look at what is possible when a family is willing to make changes in their way of life simply for the sake of love. What message could be more positive than that?

“A Nice Indian Boy” is now playing in theaters.

Movies

Sexy small town secrets surface in twisty French ‘Misericordia’

A deliciously depraved story with finely orchestrated tension

The name Alain Guiraudie might not be familiar to most Americans, but if you mention “Stranger by the Lake,” fans of great cinema (and especially great queer cinema) are sure to recognize it immediately as the title of the French filmmaker’s most successful work to date.

The 2013 thriller, which earned a place in that year’s “Un Certain Regard” section of the Cannes Film Festival and went on to become an international success, mesmerized audiences with its tense and erotically charged tale of dangerous attraction between two cruisers at a gay beach, one of whom may or may not be a murderer. Taut, mysterious, and transgressively explicit, its Hitchcockian blend of suspense, romance, and provocative psychological exploration made for a dark but irresistibly sexy thrill ride that was a hit with both critics and audiences alike.

In the decade since, he’s continued to create masterful films in Europe, becoming a favorite not only at Cannes but other prestigious international festivals. His movies, each in their own way, have continued to elaborate on similar themes about the intertwined impulses of desire, fear, and violence, and his most recent work – “Misericordia,” which began a national rollout in U.S. theaters last weekend – is no exception; in fact, it draws all the familiar threads together to create something that feels like an answer to the questions he’s been raising throughout his career. To reach it, however, he concocts a story of small town secrets and hidden connections so twisted that it leaves a whole array of other questions in its wake.

It centers on Jérémie (Félix Kysyl), an unemployed baker who returns to the woodsy rustic village where he spent his youth for the funeral of his former boss and mentor. Welcomed into the dead man’s home by his widow, Martine (Catherine Frot), the visitor decides to extend his stay as he reconnects to his old home town and his memories. His lingering presence, however, triggers jealousy and suspicion from her son – and his own former school chum – Vincent (Jean-Baptiste Durand), who fears he has ulterior motives, while his sudden interest in another old acquaintance, Walter (David Ayala), only seems to make matters worse. It doesn’t take long before circumstances erupt into a violent confrontation, enmeshing Jérémie in a convoluted web of danger and deception that somehow seems rooted in the unspoken feelings and hidden relationships of his past.

The hard thing in writing about a movie like “Misericordia” is that there’s really not much one can reveal without spoiling some of its mysteries. To discuss its plot in detail, or even address some of the deeper issues that drive it, is nearly impossible without giving away too much. That’s because it’s a movie that, like “Stranger by the Lake” and much of Guiraudie’s other work, hinges as much on what we don’t know as what we do. Indeed, in its earlier scenes, we are unsure even of the relationships between its characters. We have a sense that Jérémie is perhaps a returning prodigal son, that Vincent might be his brother, or a former lover, or both, and that’s just stating the most obvious ambiguities. Some of these cloudy details are made clear, while others are not, though several implied probabilities emerge with a little skill at reading between the lines; it hardly matters, really, because as the story proceeds, new shocks and surprises come our way which create new mysteries to replace the others – and it’s all on shaky ground to begin with, because despite his status as the film’s de facto protagonist, we are never really sure what Jérémie’s real intentions are, let alone whether they are good or bad.

That’s not sloppy writing, though – it’s carefully crafted design. By keeping so much of the movie’s “backstory” shrouded in loaded silence, Guiraudie – who also wrote the screenplay – reminds us that we can never truly know what is in someone else’s head (or our own, for that matter), underscoring the inevitable risk that comes with any relationship – especially when our passions overcome our better judgment. It’s the same grim theme that was at the dark heart of “Stranger,” given a (slightly) less macabre treatment, perhaps, but nevertheless there to make us ponder just how far we are willing to place ourselves in danger for the sake of getting what – or who – we desire.

As for who desires what in “Misericordia,” that’s often as much of a mystery as everything else in this seemingly sleepy little village. Throughout the film, the sparks that fly between its people often carry mixed signals. Sex and hostility seem locked in an uncertain dance, and it’s as hard for the audience to know which will take the lead as it is for the characters – and if the conflicting tone of the subtext isn’t enough to make one wonder just how sexually adventurous (and fluid) these randy villagers really are beneath their polite and provincial exteriors, the unexpected liaisons that occur along the way should leave no doubt.

Yet for all its murky morality and guilty secrets, and despite its ominous motif of evil lurking behind a wholesome small-town surface, Guiraudie’s pastoral film noir goes beyond all that to find a surprisingly humane layer rising above it all, for which the town’s seemingly omnipresent priest (Jacques Develay) emerges to highlight in the film’s third act – though to reveal more about that (or about him) would be one of those spoilers we like to avoid.

There’s a clue to be found, however, in the film’s very title, which in Catholic tradition refers to the merciful compassion of God for the suffering of humanity, but can be literally translated simply as “mercy.” Though it spends much of its time illuminating the sordid details of private human behavior, and though the journey it takes is often quite harrowing, “Misericordia” has an open heart for all of its broken, stunted, and even toxic characters; Guiraudie treats them not as heroes or villains, but as flawed, confused, and entirely relatable human beings. In the end, we may not know all of their dirty secrets, we feel like we know them – and in knowing them can find a share of that all-forgiving mercy for even the worst of them.

It’s worth mentioning that it’s also a movie with a lot of humor, brimming with comically absurd character moments that somehow remind us of our own foibles even as we laugh at theirs. The cast, led by the opaquely sincere Kysyl and the delicately provocative Frot, forge a perfect ensemble to create the playful-yet-gripping tone of ambiguity – moral, sexual, and otherwise – that’s essential in making Guiraudie’s sly and ultimately wise observations about humanity come across.

And come across they do – but what makes “Misericordia” truly resonate is that they never overshadow its deliciously depraved story, nor dilute the finely orchestrated tension his film maintains to keep your heart pounding as you take it all in.

To tell the truth, we already want to watch it again.

Movies

Stellar cast makes for campy fun in ‘The Parenting’

New horror comedy a clever, saucy piece of entertainment

If you’ve ever headed off for a dream getaway that turned out to be an AirBnB nightmare instead, you might be in the target audience for “The Parenting” – and if you also happen to be in a queer relationship and have had the experience of “meeting the parents,” then it was essentially made just for you.

Now streaming on Max, where it premiered on March 13, and helmed by veteran TV (“Looking,” “Minx”) and film (“The Skeleton Twins,” “Alex Strangelove”) director Craig Johnson from a screenplay by former “SNL” writer Kurt Sublette, it’s a very gay horror comedy in which a young couple goes through both of those excruciatingly relatable experiences at once. And for those who might be a bit squeamish about the horror elements, we can assure you without spoilers that the emphasis is definitely on the comedy side of this equation.

Set in upstate New York, it centers on a young gay couple – Josh (Brandon Flynn) and Rohan (Nik Dodani) – who are happily and obviously in love, and they are proud doggie daddies to prove it. In fact, they are so much in love that Rohan has booked a countryside house specifically to propose marriage, with the pretext of assembling both sets of their parents so that each of them can meet the other’s family for the very first time. They arrive at their rustic rental just in time for an encounter with their quirky-but-amusing host (Parker Posey), whose hints that the house may have a troubling history leave them snickering.

When their respective families arrive, things go predictably awry. Rohan’s adopted parents (Edie Falco, Brian Cox) are successful, sophisticated, and aloof; Josh’s folks (Lisa Kudrow, Dean Norris) are down-to-earth, unpretentious, and gregarious; to make things even more awkward, the couple’s BFF gal pal Sara (Vivian Bang) shows up uninvited, worried that Rohan’s secret engagement plan will go spectacularly wrong under the unpredictable circumstances. Those hiccups, and worse, begin to fray Josh and Rohan’s relationship at the edges, revealing previously unseen sides of each other that make them doubt their fitness as a couple – but they’re nothing compared to what happens when they discover that they’re also sharing the house with a 400-year-old paranormal entity, who has big plans of its own for the weekend after being trapped there alone for decades. To survive – and to save their marriage before it even happens – they must unite with each other and the rest of their feuding guests to defeat it, before it uses them to escape and wreak its evil will upon the world.

Drawing from a long tradition of “haunted house” tropes, “The Parenting” takes to heart its heritage in this campiest-of-all horror settings, from the gathering of antagonistic strangers that come together to confront its occult secrets to the macabre absurdity of its humor, much of which is achieved by juxtaposing the arcane with the banal as it filters its supernatural clichés through the familiar trappings of everyday modern life; secret spells can be found in WiFi passwords instead of ancient scrolls, the noisy disturbances of a poltergeist can be mistaken for unusually loud sex in the next room, and the shocking obscenities spewed from the mouth of a malevolent spectre can seem as mundane as the homophobic chatter of your Boomer uncle at the last family gathering.

At the same time, it’s a movie that treats its “hook” – the unpredictable clash of personalities that threatens to mar any first-time meeting with the family or friends of a new partner, so common an experience as to warrant a separate sub-genre of movies in itself – as something more than just an excuse to bring this particular group of characters together. The interpersonal politics and still-developing dynamics between each of the three couples centered by the plot are arguably more significant to the film’s purpose than the goofy details of its backstory, and it is only by navigating those treacherous waters that either of their objectives (combining families and conquering evil) can be met; even Sara, who represents the chosen family already shared by the movie’s two would-be grooms, has her place in the negotiations, underlining the perhaps-already-obvious parallels that can be drawn from a story about bridging our differences and rising above our egos to work together for the good of all.

Of course, most horror movies (including the comedic ones) operate with a similar reliance on subtext, serving to give them at least the suggestion of allegorical intent around some real-world issue or experience – but one of the key takeaways from “The Parenting” is how much more satisfyingly such narrative formulas can play when the movie in question assembles a cast of Grade-A actors to bring them to life, and this one – which brings together veteran scene-stealers Falco, Kudrow, Cox, Norris, and resurgent “it” girl Posey, adding another kooky characterization to a resume full of them – plays that as its winning card. They’re helped by Sublett’s just-intelligent-enough script, of course, which benefits from a refusal to take itself too seriously and delivers plenty of juicy opportunities for each of its actors to strut their stuff, including the hilarious Bang; but it’s their high-octane skills that bring it to life with just the right mix of farcical caricature and redeeming humanity. Heading the pack as the movie’s main couple, the exceptional talent and chemistry of Dodani and Flynn help them hold their own among the seasoned ensemble, and make it easy for us to be invested enough in their couplehood to root for them all the way through.

As for the horror, though Johnson’s movie plays mostly for laughs, it does give its otherworldly baddie a certain degree of dignity, even though his menace is mostly cartoonish. Indeed, at times the film is almost reminiscent of an edgier version of “Scooby-Doo”, which is part of its goofy charm, but its scarier moments have enough bite to leave reasonable doubt about the possibility of a happy ending. Even so, “The Parenting” likes its shocks to be ridiculous – it’s closer to “Beetlejuice” than to “The Shining” in tone – and anyone looking for a truly terrifying horror film won’t find it here.

What they will find is a brisk, clever, saucy, and yes, campy piece of entertainment that will keep you smiling almost all the way through its hour-and-a-half runtime, with the much-appreciated bonus of an endearing queer romance – and a refreshingly atypical one, at that – at its heart. And if watching it in our current political climate evokes yet another allegory in the mix, about the resurgence of an ancient hate during a gay couple’s bid for acceptance from their families, well maybe that’s where the horror comes in.

-

Opinions5 days ago

Opinions5 days agoIt’s time for new leadership on the Maryland LGBTQIA+ Commission

-

The White House5 days ago

The White House5 days agoWhite House does not ‘respond’ to reporters’ requests with pronouns included

-

Arts & Entertainment5 days ago

Arts & Entertainment5 days ago‘Gay is Good’ Pride Pils Can Celebrates Frank Kameny’s 100th Birthday for WorldPride in D.C.

-

Sponsored5 days ago

Sponsored5 days agoTHC Drinks: What You Should Know About Cannabis Beverages