Sports

Gay athletes talk religion and faith

Church teachings complicate coming out process for many

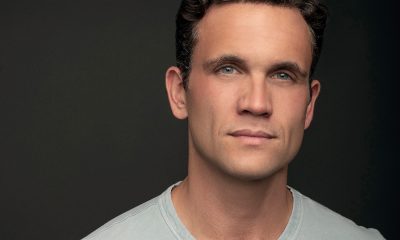

Tanner Williams (Photo courtesy of Oklahoma University Athletics)

There have been a vast number of coming out stories told recently that share a common thread that it isn’t easy to accept your sexual identity when it is not considered “normal.”

The self-acceptance process is generally filled with shame, insecurities, fear and often depression. Homophobia is exactly what you don’t want to experience when you are dealing with finding your true self.

There are other identities that you are not born with, those that are chosen, that also come with homophobia. Religion and sports can be extremely homophobic environments that can add even more emotion to the inner struggle of growing up gay.

It seems like an impossible bridge to gap. Why not just walk away from the two you can choose to walk away from, religion and sports?

Meet three men who are gay, played sports and grew up with religion. All three of them say it is not religion that bridged the three struggles, but rather their individual faith.

When you speak to Josh Sanders, there is a sense of calm that emanates from him. He describes his relationship with religion as being vertical and horizontal and more of a personal journey.

“The vertical is the relationship between me and God and the horizontal is me and the eyes of other people,” says Sanders. “I should never look at myself through the eyes of others.”

Josh Sanders (Photo courtesy of Charyln)

Sanders grew up playing basketball and intended to walk onto the team at Virginia Wesleyan but ended up dropping out to address his inner struggles. He began coaching a local high school team and enrolled at James Madison University. His path led to him to work with various Christian sports ministries and he became the athletic director at a Christian sports camp. After surviving six months of conversion therapy, he came out to his employer only to be told he couldn’t return to the sports camp position that he had held for six years because of his sexuality.

“There is an exclusive tone to the intersection between religion and sexuality. It is the church versus the gay community,” Sanders says. “I don’t separate those two parts of myself. I can be both and there is nothing exclusive about that. If you can’t acknowledge that I can be both, then you are not seeing all of me.”

Sanders, who is living in the Virginia Beach area, has been getting involved again with sports as director of external engagement for GO! Athletes. He is also involved in its extension project, GO! Faith, which provides an inclusive space for young LGBT athletes, coaches and administrators of faith to come together for fellowship and encouragement.

“Biblical literalism is alive today but I think context is everything. It makes no sense to apply those writings to life today,” says Sanders. “The Bible leads the direction of my faith, but it is my own personal interpretation.”

Sanders attends a large evangelical church on occasion that is not LGBT friendly. He says he goes there because of the loving friendships he has made with some of its members.

“We [the LGBT community] are the ones that need to take the initiative to get people from the church to step outside their own experience and actually get to know us,” Sanders says. “Once that happens, there can be change.”

Tanner Williams was so shy as a kid that he was afraid to speak to people. He would wait outside after track practice in hopes of getting through a day without being called a fag. Because of his Southern Baptist upbringing in Ardmore, Okla., he spent a lot of time in those isolated moments wondering why he was gay.

In the sixth grade, his coach got him into pole vaulting and within two years, he won a national championship and followed that up with two state championships in high school.

“I was a really religious kid and I put all my trust in God and pole vaulting,” says Williams. “I had no friends and my time was spent praying and talking to God.”

During his freshman year at Oklahoma University, the mother of a girl he had been formerly promised to for marriage, began stalking Williams through a fake Twitter and Facebook account, threatening to out him, he says. A police report was filed and security was increased at the Big 12 Championships in Waco, Texas, where Williams was competing in the pole vault for the Sooners.

“I grew up with people telling me it’s a choice to be gay and I fell for it,” Williams says. “When things like harassment happen, it just reinforces the feeling that there is something wrong with you.”

Williams began coming out to friends two years ago at age 19 and is now only occasionally attending church. He says he feels sorry for members of organized religion who propagate homophobia because they pick and choose what they believe in the Bible.

“They don’t study the bible like I do and they don’t look at it like I do.” says Williams. “I study it and find the content for me, what God wants for me.”

Williams is coming up on his senior year at Oklahoma University and will be graduating with a degree in business management and nursing. Last year at age 20 he married his partner, Scott Williams and he is looking forward to what the future has to offer.

“I love competing but I am ready to move on,” Williams says. “I will be the only senior on the Sooners track team this year so I will be stepping forward as more of a leader. I guess that’s my management side coming out.”

When Akil Patterson was playing football for the University of Maryland, his mom was commuting from Frederick, Md., to get her master’s degree and used to pick her son up for church. He always felt he wasn’t being honest because the black church he attended was adamantly opposed to homosexuality. He sometimes brought his teammates along so he would feel more comfortable. It was during one of those rides to church that Patterson came out to his mom.

Akil Patterson pictured with Washington Blade guest editor Hudson Taylor. (Photo by Kevin Majoros)

“I was struggling during my coming out process and I turned to my faith,” says Patterson. “God doesn’t get you out of things; he just helps you get through them.”

After his football career ended, Patterson returned to the University of Maryland campus and became involved with coaching for their wrestling programs. The Terrapin Wrestling Club is also a regional Olympic training center for USA Wrestling and Patterson began competing in Greco-Roman wrestling.

Recently retired from sports, Patterson still attends church and says that everything a person needs is in the Bible and subject to one’s own interpretation. He likes going to church because of the sense of camaraderie and fellowship and is attending a more affirming church now.

“When that black pastor says that being gay is wrong, everyone starts screaming and it creates a wolf pack mentality,” Patterson says. “If the pastors would stop talking about it, people in the black community would follow. They will defend you and look out for you, but they don’t want to hear about that part of you.”

Patterson said that organized religion is directed at a certain type of people, those who are not secure in their faith.

“Those people are not rooted and don’t understand how the book is translated. Too many of them think that faith is what you learned in church,” Patterson says. “The church is religion but faith is beyond that. I am a man of faith.”

Sports

Every MLB team except this one celebrated Pride

Right-wingers react to ‘backlash’ against Rangers: ‘Bullying is unacceptable’

Once again, the Texas Rangers opted not to celebrate Pride last month with a dedicated day or night on its 2024 promotion schedule. And once again, the American League West team is the only Major League operation to do so.

This repeated omission by the reigning World Series champs has sparked what one conservative news site calls a “ridiculous backlash.” As the Washington Examiner’s Kimberly Ross wrote this week:

“There is no getting away from these ubiquitous celebrations. Instead of ‘to each his own,’ major league teams are nearly required to give in and perform in an effort to placate the loudest crowds. It’s not good enough to include everyone at all times. You must kowtow or else. This kind of bullying is unacceptable, and it’s worth pushing back against whether you’re a regular citizen or the 2023 World Series champion Texas Rangers.”

But the only evidence of the “backlash” was a balanced report by Schuyler Dixon of the Associated Press that appeared on the website of KSAT-TV in San Antonio, detailing the frustrations of local LGBTQ advocates and fans. His report was posted by the AP under the headline: “Why are the Texas Rangers the only MLB team without a Pride Night?” The virulently anti-trans British tabloid, the Daily Mail rehashed that same AP piece but added that LGBTQ groups were “FURIOUS” without substantiating that claim with a single quote.

At most, DeeJay Johannessen, chief executive of the HELP Center, an LGBTQ organization based in Tarrant County, where the Rangers play, told the AP he felt “kind of embarrassed.” The Daily Mail headline writer was apparently “kind of” clickbaiting.

“It’s kind of an embarrassment to the city of Arlington that their team is the only one that doesn’t have a Pride night,” Johannessen said. Local advocate Rafael McDonnell said, “It pains me that this remains an issue [after] all these years.”

How painful? McDonnell told the AP he considered not attending the championship parade with his boyfriend when the Rangers celebrated their first World Series championship last fall. Ultimately, he decided to go. So much for “FURIOUS.”

McDonnell is the communications and advocacy manager for the Resource Center, which is an organization that grew out of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s. He added that his group has worked with the Rangers, at their invitation, to help them develop a policy of inclusion, starting about five years ago.

The team has sent employees to volunteer for programs supporting its efforts in advocating for marriage equality and transgender rights.

Although McDonnell said members of the Rangers staff keep in contact with him, he told the AP he can’t recall any conversations with the team since its five-game victory over the Arizona Diamondbacks in last year’s World Series.

“For a long time, I’ve thought that it might be somebody very high up in the organization who is opposed to this for some reason that is not clearly articulated,” McDonnell said. “To say that the Rangers aren’t doing anything for the community, well, they have. But the hill that they are choosing to stake themselves out on is no Pride night.”

The Rangers did celebrate Mexican heritage during a game last month, and also host nights throughout the season dedicated to other groups as well as the Boy Scouts, the Girl Scouts, first responders, teachers, and the military. The team also recognizes universities from around the Dallas-Fort Worth area and other parts of the Lone Star State. But not Pride.

Why? The Rangers issued a statement, very similar to one from 2023. It lists various organizations the team has sponsored and steps it has taken internally to “create a welcoming, inclusive, and supportive environment for fans and employees.”

“Our longstanding commitment remains the same: To make everyone feel welcome and included in Rangers baseball — in our ballpark, at every game, and in all we do — for both our fans and our employees,” the team said. “We deliver on that promise across our many programs to have a positive impact across our entire community.”

“I think it’s a private organization,” said Rangers fan Will Davis. “And if they don’t want to have it, I don’t think they should be forced to have it.” Davis is from Marble Falls, about 200 miles southwest of the stadium in Central Texas and attended a recent game with his son’s youth baseball team.

“I think if it were something where MLB said, ‘We’re not participating in this,’ but the MLB does participate in it. And the Rangers have chosen not to,” said Rangers fan Misty Lockhart, who lives near told the ballpark. Lockhart told the AP she attends almost three dozen games every season. “I think that’s where I take the bigger issue, is they have actively chosen not to participate in it.”

While Lockhart says she doesn’t see Pride night as a political issue, she suggested there would be more pressure on the Rangers if their stadium was downtown, in the heart of Dallas County, where the majority of elected officials are Democrats. Tarrant County, home to Arlington, Fort Worth and Global Life Stadium, is generally more conservative, just like the governor, lieutenant governor, legislature, and fans like Will Davis.

“In something like this, this is a way for people to go as a state,” Davis told the AP. “We don’t want the political stuff shoved down our throats one way or the other, left or right. We’re coming out here to have a good time with friends or family and let it be.”

Unfortunately, some Rangers fans decided they could not “let it be” the one time the team welcomed local LGBTQ groups to a game as part of a fundraising event, as it does for other groups. This was in September 2003, two years after the Chicago Cubs hosted what is considered the first-ever Pride game. At that time, Rangers fans raged about the invitation on a website, and showed up to protest outside the stadium before that game.

The Rangers never extended that invitation again.

Sports

Haters troll official Olympics Instagram for celebrating gay athlete and boyfriend

Campbell Harrison clapped back at online trolls

Olympian Campbell Harrison has already conquered an eating disorder, anxiety, depression, and disappointment for skipping the Tokyo Summer Games so he could support his older sister in her battle with cancer.

So, he’s saying “no wucka’s” (meaning, “no problem” in Aussie lingo) to the bigots, trolls, mongrels, and “drongos” (meaning, “dicks” and “fools,” respectively) who plastered their disapproval in the comments of an Instagram post celebrating him as the first LGBTQ sport climber in Olympic history.

The post wasn’t even his; the official Olympics Instagram account shared pictures from his qualifying climb from November 2023, and tagged Harrison earlier this week.

“Celebration kiss for the ages 😘🌈” reads the caption. “After not making it to Tokyo 2020, Australian sport climber Campbell Harrison did not give up and four years later secured a quota spot for the Olympic Games #Paris2024. It was an emotional victory celebrated together with his partner, Justin.”

Harrison, having seen the negative comments multiply, took them in stride with a snappy response that included a tag to his boyfriend, Justin Maire, whose account is private.

“All these people mad cause we’re hotter than they are 😘,” Harrison wrote.

Harrison’s mother, Yvette, shared her support: “I could not be more proud of you my beautiful son. You and Justin are such a beautiful couple and we love you both very much. 🏳️🌈🙌❤️”

There were plenty of other supportive comments, and haters were called out, too: “I love all the people following the @Olympics page due to the Olympic spirit (among other values), who don’t see the irony of bashing an Olympic athlete because of who they love,” wrote out travel writer and LGBTQ rights advocate Mikah Meyer.

The person managing the official Olympics Instagram account was asked to do a better job curating the comments, which were largely vitriolic and cruel. The account posted this plea: “Let’s keep our community positive ❤️ Please ensure your comments are respectful and avoid any language that could be offensive, or harmful to others. We reserve the right to remove comments that do not adhere to this guideline.”

Gay Olympic champion diver Matthew Mitcham commented: “15 years ago I kissed my partner on camera when I won in Beijing 2008. This one post by @olympics has received more hate than I did in my whole career.”

Today is Harrison’s 28th birthday. He, his boyfriend and his mother recently spoke with Climbing’s Holly Yu Tung Chen. She wrote:

“Campbell arrived in the world on June 28, 1997, screaming inconsolably. Unlike his three other siblings, who were all ‘peaches and cream,’ said Yvette, baby Campbell was “squishy and cuddly, yes — but he had a lot to say from the word go.”

“Campbell started climbing at age eight when Russell took the children to the Victorian Climbing Centre and noticed Campbell’s immediate vigor. It’s the age-old climber tale: Campbell almost immediately lost interest in the other sports he dabbled in, including swimming, soccer, and track and field. All he wanted to do was climb.”

Harrison told Climbing although he never actually “came out” as gay, he never hid his sexuality, and simply made sure his parents and siblings knew who he was. For example, when he told the family he’d be joining Climbing Cuties, an affinity group for queer climbers, they told him to have fun. On another occasion, Harrison let them know he’d be taking part in a panel for queer climbers, and his parents asked if they could attend.

As for his boyfriend, Harrison told Climbing they met cute.

“In the age where most people meet online, we had the classic story of catching each other’s eye from across the room,” said Harrison. Maire told the reporter he recognized Campbell from social media, where the climber does not hide their relationship, and that often results in comments that his posts have “gotten too political.”

“How is that political?” he asked, rhetorically, noting that most of the hateful comments he receives online come from Americans. “Why should I change the way I feel just because of someone else’s perception of me?” he said.

Last November, the only climber to top the men’s finals route during the IFSC Oceania Qualifier in Melbourne was Harrison. Watching him ascend were his parents and boyfriend, as he clipped the final draw and collapsed inward, his hands covering his face as he was lowered down. He had punched his ticket to Paris with this win.

Once he was on the ground, Harrison made a beeline to Maire, where they hugged and kissed, as recorded on Instagram.

The Washington Mystics will be having their upcoming Pride game on Saturday against the Dallas Wings.

The Mystics Pride game is one of the team’s theme nights they host every year, with Pride night being a recurring event. The team faced off against the Phoenix Mercury last June. Brittney Griner, who Russia released from a penal colony in December 2022 after a court convicted her of importing illegal drugs after customs officials at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport found vape canisters with cannabis oil in her luggage, attended the game.

Unlike the NBA, where there are currently no openly LGBTQ players, there are multiple WNBA players who are out. Mystics players Emily Englster, Brittney Sykes, and Stefanie Dolson are all queer.

The Mystics on June 1 acknowledged Pride Month in a post to its X account.

“Celebrating Pride this month and every month,” reads the message.

Celebrating #Pride this month and every month 🏳️🌈🫶 pic.twitter.com/yFhDoggAVZ

— Washington Mystics (@WashMystics) June 1, 2024

The game is on Saturday at 3 p.m. at the Entertainment and Sports Arena (1100 Oak Drive, S.E.). Fans can purchase special Pride tickets that come with exclusive Mystics Pride-themed jerseys.

-

Canada1 day ago

Canada1 day agoToronto Pride parade cancelled after pro-Palestinian protesters disrupt it

-

Theater4 days ago

Theater4 days agoStephen Mark Lukas makes sublime turn in ‘Funny Girl’

-

Baltimore3 days ago

Baltimore3 days agoDespite record crowds, Baltimore Pride’s LGBTQ critics say organizers dropped the ball

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoHaters troll official Olympics Instagram for celebrating gay athlete and boyfriend